Editorial: Neither Wickedness Nor Sorrow

It is a summer evening of perhaps 1812, as described in Jane Austen's Mansfield Park; the scene is the music room in the great country house of a wealthy English baronet. While their companions gather at the pianoforte, two young people, Frances "Fanny" Price and her adored cousin Edmund Bertram, stand at a window looking out at the stars

. . . where all that was solemn and soothing, and lovely, appeared in the brilliancy of an unclouded night, and the contrast of the deep shade of the woods. Fanny spoke her feelings. "Here's harmony!" said she, "Here's repose! . . . . Here's what may tranquilise every care, and lift the heart to rapture! When I look out on such a night as this, I feel as if there could be neither wickedness nor sorrow in the world; and there certainly would be less of both if the sublimity of Nature were more attended to, and people were carried more out of themselves by contemplating such a scene."

Given the setting, one might think that the speaker is a naive and sheltered heiress, ignorant of the cruelties of the powerful and the suffering of the defenseless in the world of two hundred years ago. But such is not the case. Fanny is not a daughter of the house but a penniless relative, unofficially adopted at age ten from the squalid household of uncaring parents. In this huge luxurious house her bedroom is a small unheated attic. She is ordered about by her two aunts, sometimes worked beyond her strength, and made to feel her inferior status at almost every turn. The chief abuser is her Aunt Norris (the name is derived from a notorious plantation manager), whose verbal attacks relentlessly work on her nervousness and insecurity. And far from being ignorant about social evil, the sensitive Fanny is well-read on current events, including the struggle against human slavery.

What we have here then is a most extraordinary situation: a wounded soul, victim of longterm, ongoing child abuse and neglect, who when she looks at the stars "feels as if there could be neither wickedness nor sorrow in the world"! Knowing and feeling, mind and heart seem hopelessly at odds. She asserts that evil and sorrow do not exist in the face of her painful daily experience of both; and she remains convinced that they would be lessened if people would spend more time contemplating the night sky, and thus be "carried out of themselves" into rapture, as she now is.

What we have here then is a most extraordinary situation: a wounded soul, victim of longterm, ongoing child abuse and neglect, who when she looks at the stars "feels as if there could be neither wickedness nor sorrow in the world"! Knowing and feeling, mind and heart seem hopelessly at odds. She asserts that evil and sorrow do not exist in the face of her painful daily experience of both; and she remains convinced that they would be lessened if people would spend more time contemplating the night sky, and thus be "carried out of themselves" into rapture, as she now is.

Significantly, Fanny's rapture is brief: her beloved drifts away from the starlit scene toward the candlelit one; he forgets the celestial harmony in favor of a popular song (led by another woman, with whom he is falling in love). Fanny sighs alone at the window until Mrs. Norris scolds her away.

There has been very little critical comment about the paradox in this scene, but it is worth a second look. I believe it contains a strain of hope for those of us who, if not ourselves victimized by human wickedness, do share deeply in the sorrow and anguish of our kin who are, and sometimes feel bitterly helpless to do much about the institutional evil that causes it. But the scene is dark in more ways than one. I see one explanatory hint in the heroine's name. Though she is always referred to as Fanny (then a common and acceptable diminutive), there is no question but that her real name is Frances, after her mother. And there are a number of suggestions that she is a nature mystic, a spiritual daughter of the beloved saint of Assisi who was the first in the West to give voice to the conviction that all things and beings in nature, stemming from the same Source as ourselves, are our brothers and sisters. In nature this Frances finds the only tender, nurturant parent she has ever known. Contemplating its scenes gives her peace, arouses her sense of wonder and gratitude, renews her hope. She finds guidance in the nature poetry of William Cowper, who speaks of perceiving in nature "the unambiguous footsteps of the God / Who gives [the] lustre to an insect's wing, / And wheels his throne upon the rolling worlds. " There is also a suggestion that she loves Wordsworth's poetry, with its reflections on feeling the presence of the same life-giving spirit blowing through nature and humanity.

If we see her as a nature mystic, it is unsurprising that Fanny's sorrow, at least, is lessened as a result of contemplating the starlight. Jay McDaniel, philosopher and friend to all creation, casts further light on the process in his book Living From the Center:

Sometimes, if something terrible has happened . . . it can help to follow the advice of Walt Whitman . . . . to go outside on a clear night and gaze into the dark and starlit sky . . . .

The sky and its stars can be a holy icon, an enfolding womb in which we feel small but included in a greater wholeness. The greater wholeness is God, the Open Space. The moist night air, which gives freedom and freshness to our souls, is God's Breathing.

We experience this Breathing in two ways. First, . . . through the healing grace of the sky itself, which reminds us that there is something more to the universe, much more, than is contained in our suffering, no matter how intense it might be. Here, the sky functions as a stained glass window through which divine light shines: a dark light, to be sure, but a holy light as well.

Second, we experience the Breathing through our own internal . . . wonder at the spectacle of the sky, through our delight in the beauty of its thousand points of light. In our amazement God breathes as deeply as in the sky itself. Complementing this amazement, there can also emerge an additional and more subtle feeling: a sense of opening out into the night sky and trusting the mysterious [P]resence, the dark mystery, that shines through it . . . . This opening out into trust is what I mean by "faith" . . . .

Of course, not everyone who has the opportunity to see a clear sky full of stars consciously experiences this Presence, but most who do have the opportunity can sense something of that awakened awe, feel something of its power to lessen sorrow, even if not as intensely as a mystic like Fanny might. Jay McDaniel affirms this process when he goes on to say,

Faith has a healing effect in our lives . . . . But it does not do so by changing the objective situation. Rather, it does so by giving us the inner resources to deal with a bad situation, no matter how horrible it might be.

This is a blessing to be cherished. But how could attending to the stars possibly lessen wickedness? Even more, how could there be any reality behind Fanny's feeling that neither wickedness nor sorrow can exist? As we noticed from the close of Austen's scene, the evil incarnate in Mrs. Norris is definitely still there, not at all diminished by the numinous Presence in the starry night, and there is no sign in the story that she would behave with less cruelty even if she attended to it.

This is a blessing to be cherished. But how could attending to the stars possibly lessen wickedness? Even more, how could there be any reality behind Fanny's feeling that neither wickedness nor sorrow can exist? As we noticed from the close of Austen's scene, the evil incarnate in Mrs. Norris is definitely still there, not at all diminished by the numinous Presence in the starry night, and there is no sign in the story that she would behave with less cruelty even if she attended to it.

But we can perhaps gain some understanding of a reality behind Fanny's extraordinary claim by looking briefly at the concept of the mysticism of union. The union in question refers not only to the experience of the mystic that in her rapture she is united with the Divine/Ultimate, but affirms an intuition that all things, all concepts and categories, including opposites, are finally One. Speaking both experientially and as a philosopher of religion, William James (who in his personal life dealt both with deep depressions and the death of his little son) says in his classic text The Varieties of Religious Experience,

Looking back on my own experiences, they all converge towards a kind of insight . . . . The keynote of it is invariably a reconciliation. It is as if the opposites of the world, whose contradictoriness and conflict make all our difficulties and troubles, were melted into unity. Not only do they, as contrasted species, belong to one and the same genus, but one of the species, the nobler and better one, IS ITSELF THE GENUS AND SO SOAKS UP AND ABSORBS ITS OPPOSITE INTO ITSELF (emphasis in original).

To some readers, statements such as this will ring true, however little sense they make literally; for others, they will remain meaningless, unless perhaps they are cast into the future tense, as in Lady Julian's saying: "All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well."

Either way, the value of such claims, as of the feelings of union underlying them, is in their workability: their ability to enable us to be "carried out of ourselves," out of our encapsulation and separateness, to a realization that we are one. The cultural wickedness that leads to the vast suffering and sorrow of human and animal slavery is based on the illusion of encapsulation; it regards the slave as a separate thing, an object that serves the benefit of the separate master. An experience and a conviction that we are not confined to separate capsules but are all One can empower us to take liberating action on behalf of both our human and our animal kin, and to keep on keeping on, even when the stars are invisible in the light of common day.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

The skyscape shows Orion. The second photo is of Frances O'Connor, who portrayed Fanny Price in the 1999 Patricia Rozema film. The third photo is Anna Massey as Mrs. Norris in the 1983 BBC film.

Unset Gems

"I purr, therefore God is."

"I purr, therefore God is."

--Jay McDaniel

"Everyone's a pacifist between wars. It's like being a vegetarian between meals."

--Colman McCarthy

News Notes

Consumers of the Amazon

Almost all Western consumers are funding the death of the Amazon rainforests. A new report by Greenpeace indicates that the cattle industry is the single biggest cause of deforestation in the Amazon, as trees are cleared to make way for ranches. The deforestation of the Amazon jungle supplies leather, flesh, and wood to the makers of such brands as Adidas, Reebok, and Nike shoes, Timberland, Tesco, BMW, and IKEA products, and Kraft Foods (and, of course, the fast-food hamburger chains). To read the full article see

en.mercopress.com/2009/06/01/brazilian-beef-industry-blamed-for-amazon-deforestation.

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

Low-Carbon Menus

Yes--that's low-carbon, not low-carbohydrate! A number of major food service companies who serve college cafeterias and hospitals are moving in the direction of a lower-carbon, lower-methane footprint. One is Bon Appétit, which is replacing one quarter of its flesh and dairy dishes with vegan ones. They report good reception by diners. Sodexo, which serves about ten million people worldwide, plans a similar program. The group Physicians for Social Responsibility is helping hospitals in the San Francisco Bay area to promote meat-reduced menus healthier for both patients and planet.

Letters

Dear Peaceable Friends,

I enjoyed the June PT. I must say that wonderful clip of the lion reunion was so memorable! I'd not seen that before. I also appreciated the message in the editorial. The point that once the thorn is removed from our consciousness we can't bear to participate in violence such as eating meat is tricky, when I think of people who look at pictures of the violence in the flesh industry openly and sincerely, but just aren't moved to the same degree of sadness as we are. It's hard when people just don't feel things, isn't it?

I enjoyed the June PT. I must say that wonderful clip of the lion reunion was so memorable! I'd not seen that before. I also appreciated the message in the editorial. The point that once the thorn is removed from our consciousness we can't bear to participate in violence such as eating meat is tricky, when I think of people who look at pictures of the violence in the flesh industry openly and sincerely, but just aren't moved to the same degree of sadness as we are. It's hard when people just don't feel things, isn't it?

I really want to make that tomato sauce; it sounds delectable. I also liked the reviews.

--Fay Elanor Ellwood

A Glimpse of the Peaceable Kingdom

"The bird shall dwell with the cat, their young shall lie down together . . . ."

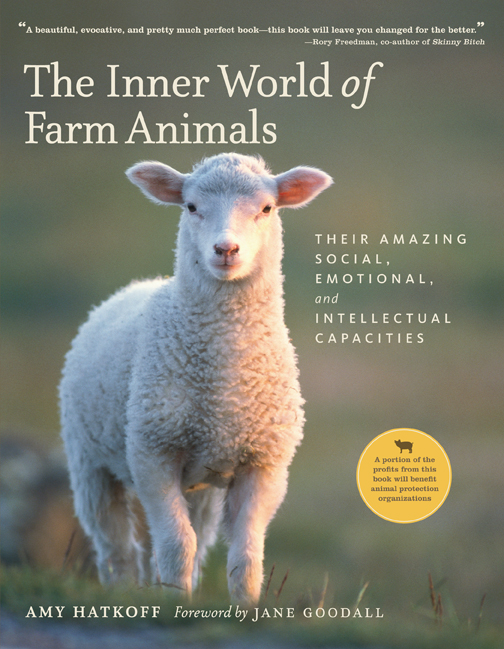

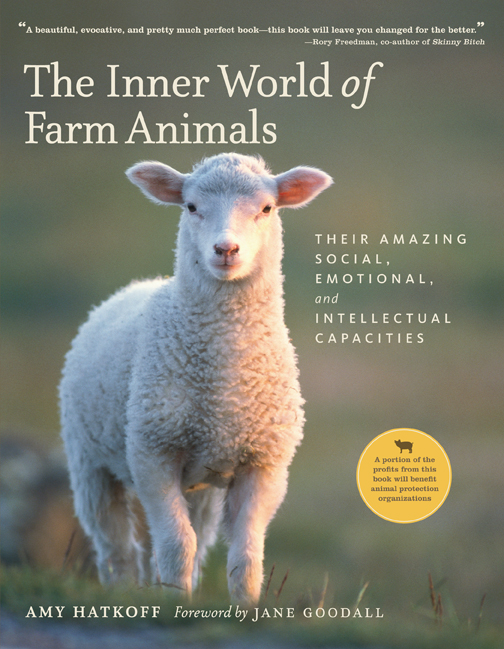

Book Review: The Inner World of Farm Animals

Amy Hatkoff, The Inner World of Farm Animals. Forward by Jane Goodall. Afterword by Wayne Pacelle, President of the HSUS. Full-color photographs by Bob Esposito and others. New York: Stewart, Tabori and Chang, 2009. 176 pages. Hardcover. $19.95.

Jane Goodall's Forward to this book is highly encouraging, because she sounds much more strongly pro-vegetarian than she did four years ago. On the other hand, the Introduction by Amy Hatkoff, though generally excellent, has the one statement in the whole book with which I have to disagree: "The Judeo-Christian view holds that only humans were created in God's image and that therefore, the purpose of animals is to be of service to mankind." (Page 16). This is one-sided and misleading. There is a strong and growing pro-animal tradition in both Jewish and Christian thought that holds that animals receive their spirit from God just as humans do, and as such, have a right to life and joy. The view Ms. Hatkoff mentions, though distressingly common in the West, in fact owes more to Aristotle than to the Bible.

Jane Goodall's Forward to this book is highly encouraging, because she sounds much more strongly pro-vegetarian than she did four years ago. On the other hand, the Introduction by Amy Hatkoff, though generally excellent, has the one statement in the whole book with which I have to disagree: "The Judeo-Christian view holds that only humans were created in God's image and that therefore, the purpose of animals is to be of service to mankind." (Page 16). This is one-sided and misleading. There is a strong and growing pro-animal tradition in both Jewish and Christian thought that holds that animals receive their spirit from God just as humans do, and as such, have a right to life and joy. The view Ms. Hatkoff mentions, though distressingly common in the West, in fact owes more to Aristotle than to the Bible.

The book has five chapters: 1- Chickens, 2- Geese, Ducks, and Turkeys, 3- Cows, 4- Pigs, and 5- Sheep and Goats. Each chapter is divided in a well-balanced way between text and beautiful color photographs. The text, in turn, provides a balance between scientific studies and uplifting anecdotes about individual birds and beasts, speaking to the concerns both of mind and heart.

It is appropriate that the first chapter should be about hens and roosters and their babies, because we humans do so much evil to these poor birds that we have long had a vested interested in insisting that they are not sentient. But they most emphatically are. In fact, the most amazing lesson I learned in this book is on page 22: "Given a choice between receiving a small amount of food immediately or a larger amount in the future, [chickens] will choose the latter, demonstrating self-control and the capacity to delay gratification." This impresses me very much because many human children have a hard time learning this, and too many adult humans never learn it. There is no pre-eminence of a Man above a Bird.

The section on geese is much too short: Only two pages (46-47), plus a couple of photographs (57-58, 151). There is one quote from Dr. Konrad Lorenz on page 46. He discovered that geese "exhibit the same physical signs of grief as humans. Their eyes sink, their bodies droop and their heads hang." Dr. Lorenz spent many years studying geese - never inflicting any physical harm or emotional distress on them - and became the world's leading expert on them. Much more that he learned could have been included here. I was a bit disappointed that his writings are not included either in the list of books (pp 166-167) or in the bibliography (170-171). I would like to recommend just one, the very fine King Solomon's Ring.

His finding that geese mourn just as humans do is also true of other animals in the book. When it comes to both joy and grief, and to love and friendship, there is no real difference between us and the rest of the vertebrates. Significantly, we all can learn better when we are happy.

A notable insight from the chapters on sheep and cows: both are much better at distinguishing humans from one another than your average human is in distinguishing a cow from a cow or a sheep from a sheep (although I suspect the animals also have the help of their sense of smell). This superior perceptiveness means they have an intelligence greater than ours in this area. In a story on page 134, some readers of PT will recognize Rambo, the wonderfully altruistic and compassionate ram featured in our Jan. 2009 editorial (See PT50).

A notable insight from the chapters on sheep and cows: both are much better at distinguishing humans from one another than your average human is in distinguishing a cow from a cow or a sheep from a sheep (although I suspect the animals also have the help of their sense of smell). This superior perceptiveness means they have an intelligence greater than ours in this area. In a story on page 134, some readers of PT will recognize Rambo, the wonderfully altruistic and compassionate ram featured in our Jan. 2009 editorial (See PT50).

Readers of tender sensibilities will be happy and grateful that this book does not dwell on the horrors of the factory farm and the slaughterhouse. Resources are listed at the end of the book for those who wish to combat those atrocities.

The marvelous photographs in this volume are one of its strong features, making it an excellent coffee-table book. Perhaps the best one is that on page 57, showing two ducklings with smiling faces, enjoying each other's company.

I strongly recommend this book for children who are learning to read, who will delight in the photographs; for persons who love our animal cousins and want to learn more about them; and for those still in the process of deciding whether to become vegan. It will be especially valuable for those who think they have no interest at all in animals--and who are likely to be captivated in spite of themselves.

-Benjamin Urrutia

Book Review:

Stacy O'Brien, Wesley the Owl. New York: Free Press, 2008. 230 pages. $23.00 hc

Wesley the Owl is the latest in a memorable recent series of books by women of science about their bird-companions, in which science, cohabitation, and in a real sense love-interest combine in an adventure that leaves the reader thinking very differently than before about birds, and perhaps also about humans and their inter-species capabilities. There was, for example, Irene Pepperberg's Alex and Me (see PT49), and before it Joanna Burger's The Parrot Who Owns Me. Wesley, starring a barn owl, has a somewhat different feel from those parrot books, though it is certainly of no less interest. For one thing, owls are not talkers. In parrot narratives, much of the fascination lies in the bird's ability to speak and display signs of remarkable intelligence even in human terms; one always wonders what that avian-genius is going to say and do next. Owls will never use words like parrots, nor (despite the folklore about their wisdom) quite equal them in brains. Yet, the better you know them (as with any animal) the more surprises you encounter, as Stacy O'Brien found, in their stages of development, their adaptability to new situations, and -- yes -- their ability to relate profoundly to a human companion.

Wesley the Owl is the latest in a memorable recent series of books by women of science about their bird-companions, in which science, cohabitation, and in a real sense love-interest combine in an adventure that leaves the reader thinking very differently than before about birds, and perhaps also about humans and their inter-species capabilities. There was, for example, Irene Pepperberg's Alex and Me (see PT49), and before it Joanna Burger's The Parrot Who Owns Me. Wesley, starring a barn owl, has a somewhat different feel from those parrot books, though it is certainly of no less interest. For one thing, owls are not talkers. In parrot narratives, much of the fascination lies in the bird's ability to speak and display signs of remarkable intelligence even in human terms; one always wonders what that avian-genius is going to say and do next. Owls will never use words like parrots, nor (despite the folklore about their wisdom) quite equal them in brains. Yet, the better you know them (as with any animal) the more surprises you encounter, as Stacy O'Brien found, in their stages of development, their adaptability to new situations, and -- yes -- their ability to relate profoundly to a human companion.

Barn owls are also, unlike parrots, carnivores who must live almost entirely on whole mice: typically three or four a day. Every part of the mouse, even the coat for roughage, is nutritionally essential, and nothing else will do. Stacy was forced to obtain these mice from laboratories and pet shops, and despite dislike for the job often kill them herself; some readers may be repelled by these descriptions, but they are an unavoidable part of the story. Tales of Stacy and the mice add a unique dimension to her writing, such as the time a paper bag full of live mice ate their way through the container and were all over the back seat of her car, terrifying a filling-station attendant who looked in.

Moreover, Stacy O'Brien is a different writer from the others, and one senses a different kind of personality lies behind the writing. While she long worked in the ornithological laboratory at the prestigious California Institute of Technology, from whence she obtained the injured Wesley when he was four days old and for which she kept valuable notes on his development and behavior, she was not strictly a professional academic. She later had other jobs, but continued on with Wesley. Clearly a charming, sociable person of considerable beauty, she describes in some detail how she lost at least two suitors who were not as enamored of Wesley as with her, and finally couldn't take her "Love me, love my owl" policy. Her accounts of Cal Tech and its eccentric, brilliant scientists exploring incredibly arcane fields of research are head-shakingly wonderful -- I had no idea how eccentric or how brilliant till reading O'Brien, even though we lived within a few blocks of Cal Tech for more than a decade.

Stacey has a real gift for lively, often humorous writing which, unlike some books regarding animals, is never superficial or lacking at the same time in sharp insight into the subject's feelings and behavior. The story of Wesley's sexual maturation and how he decided Stacy was his mate is truly an unforgettable classic. The bird actually deposited semen on her arm, and tried to put mice in her mouth -- a female barn owl remains on the nest almost continuously, while her mate brings her and the hatchlings mice; Stacy tried pretending to eat and then concealing the mouse-corpse, but Wesley was not fooled and would keep finding it and bringing it back. Yum.

Other entertaining episodes include the time four dead mice fell into a frying-pan in front of Stacy's mother's gentleman friend, who had not been told about Wesley and his diet; and, more poignantly, the wild female barn owl who liked to come up to Stacy and Wesley's window, talking affectionately and evidently trying to get close to him. Stacy longed to let Wesley out, but knew he could not survive in the wild.

Wesley lived some nineteen years, more than a normal lifespan for his species. There is sadness toward the end; Stacy herself came to suffer from an inoperable brain tumor, nearly fatal until the condition was finally stabilized. Only her deep commitment to Wesley saved her from suicide. It was not long afterwards that the aged bird inevitably declined and died. But, as Stacy makes clear, their love was forever. Indeed, in a few restrained but meaningful passages, one understands that life with Wesley convinced the author of the reality of spirit and God. She also came, by experience, to appreciate the growing belief that telepathic communication can take place between humans and animals.

Wesley lived some nineteen years, more than a normal lifespan for his species. There is sadness toward the end; Stacy herself came to suffer from an inoperable brain tumor, nearly fatal until the condition was finally stabilized. Only her deep commitment to Wesley saved her from suicide. It was not long afterwards that the aged bird inevitably declined and died. But, as Stacy makes clear, their love was forever. Indeed, in a few restrained but meaningful passages, one understands that life with Wesley convinced the author of the reality of spirit and God. She also came, by experience, to appreciate the growing belief that telepathic communication can take place between humans and animals.

Readers of The Peaceable Table will find much to reflect on in Wesley the Owl. Their carnivorism, painful as it may be, is part of the biosphere, and Stacy's experience with Wesley and his mice helps us understand it. This author is passionate in her defense of biologists -- at least those she knew at Cal Tech -- and the love she saw they had for the animals with which they worked in the laboratory and sometimes, like her, took home to live with them. (She knew of a family home with free-range monkeys, and a bachelor with a yard full of spiders.) She is highly critical of the group of animal activists who once raided Cal Tech to release some vultures, resulting merely in their injury or early deaths in a wild free world for which they were not prepared. Readers may differ, as I would to some extent, but Stacy has been there and deserves to be heard.

Add Wesley the Owl to your animal companion shelf.

--Robert Ellwood

Recipes

Ginger Tamari Stir Fry

Serves 2 – 3

1 ½ cups sprouted chickpeas

2 carrots, peeled and julienne cut

½ lb. mushrooms, sliced

2 scallions, sliced

1 cup peas, fresh or frozen

2 T. extra virgin olive oil

Sauce:

3 T. wheat-free tamari

2 T. extra virgin olive oil

1 T. agave

1 tsp. ground ginger

¼ tsp. sea salt, or to taste

¼ tsp. red pepper flakes

1 T. cornstarch

1 ¼ cup water

Sesame seeds for garnish

In large skillet, warm olive oil. Sauté chickpeas, carrots, mushrooms and scallions until tender, about 8 minutes. Add peas, stir well to mix.

Meanwhile in a large mixing cup (4 cup capacity), whisk together sauce ingredients. Pour over vegetables, cook over medium–high heat, stirring constantly until thickened and bubbling. Remove from heat. Serve over basmati or brown rice. Garnish with sesame seeds. This dish is especially fun to eat with chopsticks.

Sprouting chickpeas is fun and easy. I start with dried organic chickpeas. Rinse the chickpeas and soak for a few hours (4 – 6 hours is good). Place the rinsed and drained chickpeas in a large, fairly wide mouth Mason jar. Cover with natural food-grade cheesecloth – secure the cloth with a rubber band. Rinse the chickpeas at least twice a day. Keep out of direct sunlight, but make sure they get plenty of indirect sunlight. The beans will sprout in a few days, and will be ready to eat in about 5 days.

Enjoy!

-- Angela Suarez

Frozen Vanilla Tofu Cream for Canine Friends

Makes about 2 ½ - 3 cups

1 lb. soft tofu

2 T. ricemilk or soymilk, vanilla flavor

1 T. evaporated cane juice

2 tsp. vanilla extract

1 tsp. fresh lemon juice

⅛ tsp. sea salt

Place all ingredients in blender or food process; and process until very smooth. Pour into plastic container with tight fitting lid and freeze. Remove from freezer; allow to slightly soften. Scoop into bowl for your best friend.

--Angela Suarez

My Pilgrimage: James Frieden

I Never Expected Revelation

I never sought spiritual revelation. I distrusted the idea of life-altering experiences in which people suddenly gained a new relationship with the universe. Surrounded by people who led happy and productive lives without strong religious feeling, I was surprised when revelation grabbed me, lit up my world, and gave me a new place in the universe.

My revelation came not from thought, nor in a flash of insight, nor in a flood of emotion enhanced by the swell of music. Revelation requires an opening of the heart. It came from the very practical everyday act of putting food in my mouth with a commitment that no animal would have died or suffered so that I could taste his flesh or drink her milk.

The Journey

My parents, confirmed meat eaters, taught me the Golden Rule: “Do unto others, as you would have others do unto you." This was the first step toward a destination far different from anything my parents had in mind. Another: on holiday some thirty-five years ago, influenced by the fiction of Ernest Hemingway and seeking the romance of Spain, my wife and I attended a bullfight. We saw a magnificent animal facing a matador. Enraged by the picadors and taunted by the matador, the bull repeatedly charged toward his death. But my wife and I noticed that he was urinating continually, and we started to think about the scene from the bull’s perspective. The walls of the stadium gave him no escape. Thousands of people screamed and trumpets blared. Men on horseback kept poking at him and the matador waved the red cape. This massive beast was bewildered and scared; he died in confusion and agony. That was our first, and last, bullfight.

The journey to revelation would stall for years at a time, but as life went on, my wife and I gathered pieces of information, scattered here and there.

For about twelve years, recognizing the brutality of factory farming, I ate neither meat nor fowl, consuming only seafood, dairy, and plant based foods. But there was no revelation in this half-way measure. As we learned more about the way that animals are treated on farms, we realized that being caught in the machinery of the dairy industry is perhaps the worst fate for any animal. The life of a dairy cow on a mechanized farm is an endless cycle of giving birth and suffering agonizing loss. When their milk production dips, dairy cows are sold to the slaughterhouse to be gutted and ground up for hamburger. Better never to have been born than to suffer that life.

Another station on my journey occurred when my wife introduced me to philosopher Peter Singer’s book, Animal Liberation. Professor Singer points out that human beings can thrive on a plant-based diet with a Vitamin B-12 supplement. This means that we kill animals for food only because we like flesh, the taste and the texture. He points out that torturing and killing animals because we like to eat meat and milk products elevates the most trivial of our interests (taste and convenience) above the most vital of theirs (avoiding misery and remaining alive). Looking to the Golden Rule: would I want my life made miserable or even taken away, just because someone or something liked the way I tasted? It took decades for me to grasp the full meaning of the ideas in Singer’s book.

The final stage of my journey to revelation began when a restaurant served me an entire fish, battered and fried. As I looked at the dead eye of what was once a swimming, shimmering beauty, I realized that I had to stop being a party to death just to eat a tasty meal. Over the next few weeks, troubled by my inability to justify killing any animal merely for food, I resolved to eat a fully plant-based diet.

Opening My Heart – and then Soaring

At first, my thrice daily ritual of eating food that wasn’t tainted with suffering and death was merely a discipline. However, after a few weeks I realized that a tremendous weight, a weight of which I had never been aware, had lifted from my shoulders. For days, I felt incredibly light, no longer carrying on my emotional back the suffering of sentient beings killed for my food. I didn’t realize it, but revelation was coming.

When we view animals as commodities to be killed or living machines to be milked, we cut ourselves off from a natural fellow feeling with other sentient earthlings. Even when I had eaten only dairy and fish, I had relied upon denial to protect myself from the painful history of what I put into my mouth. My denial about the torture of dairy cows and the killing of fish had kept me from realizing a full brotherhood with all living creatures. In the weeks leading up to revelation, my mind broke loose from the chains of denial and my soul could soar.

My heart suddenly opened up to all living creatures. I realized that my loyalty lay with all the striving, wriggling mass of living things, in all our incredible diversity, in our adamant denial of entropy. No longer separated, I was pulled up by revelation and my consciousness seemed to expand throughout the universe. There was joy and happiness just in being. The quantum of love that I could give had expanded a thousandfold.

Philosophically and logically, I can pick holes in my position. Does a slug or a mussel feel pain as mammals do? I don’t know, but I have to draw the line somewhere. And what about the indirect effects of development, when animals are displaced for farms, houses, roads, factories or parks?

These are issues that I worry about, but in my six decades I have learned that life is seldom a matter of absolutes. I don’t know of any animal that can exist without impinging in some way on the lives of others. However, despite all the moral ambiguities, the unanswered questions, and the compromises with which I live, eating with compassion has allowed me to achieve an escape velocity that has taken me to a state of expanded consciousness beyond anything I had ever thought possible.

Over the years the first rush of feeling and amazement, this opening of my heart to life, has settled down to a pervasive feeling of happiness. I may sometimes be tempted, but the wonder of life pulls me away from the food of torture and death. This is the revelation that has grabbed hold of me and which carries me along from day to day and year to year. I cannot imagine ever letting it go.

Poetry: Jane Austen, Walt Whitman

Nature Mystic at Mansfield Park

The stars are brilliant; all the clouds are fled;

The woods lie shaded deep. Here’s harmony!

Here is repose! Here’s what may leave all art,

All music far behind, what poetry

Alone can attempt to describe. And here

Is what can tranquilise our every care

And lift the heart to rapture! . . .

When I look out on such a night as this

I feel there could be neither wickedness

Nor sorrow in the world; and certainly

There would be less of both if the Sublime

In Nature were but more attended to

And we were carried more out of ourselves

By contemplating such a scene. It’s been

So long a time since we have gazed at the stars;

I cannot think why we forgot so long.

There is Arcturus looking very bright;

Yes, and the Bear. I wish I could see Her,

Cassiopeia the Queen. We must go out

Of doors for that; should you be afraid? . . .

But if we stay until the glee is finished

And join the others in the candlelight

Around the pianoforte, you may want

The glee once more; you may forget once more

And lose your bearings.

--Jane Austen and Another Lady

When I heard the Learn’d Astronomer

When I heard the learn’d astronomer;

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me;

When I was shown the charts and the diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them;

When I, sitting, heard the astronomer, where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon, unaccountable, I became tired and sick;

Till rising and gliding out, I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

--Walt Whitman

The Peaceable Table is

a project of the Animal Kinship Committee of Orange Grove Friends Meeting, Pasadena, California. It is intended to resume the witness of that excellent vehicle of the Friends

Vegetarian Society of North America, The Friendly

Vegetarian, which appeared quarterly between 1982 and

1995. Following its example, and sometimes borrowing from its

treasures, we publish articles for toe-in-the-water

vegetarians as well as long-term ones.

The journal is intended to be

interactive; contributions, including illustrations, are

invited for the next issue. Deadline for the September issue

will be August 29, 2009. Send to graciafay@gmail.com

or 10 Krotona Hill, Ojai, CA 93023. We operate primarily

online in order to conserve trees and labor, but hard copy

is available for interested persons who are not online.

The latter are asked, if their funds permit, to donate $12 (USD) per year. Other

donations to offset the cost of the domain name and server are welcome.

Website: www.vegetarianfriends.net

Editor: Gracia Fay Ellwood

Book and Film Reviewers: Benjamin Urrutia & Robert Ellwood

Recipe Editor: Angela Suarez

NewsNotes Editors: Lorena Mucke and Marian Hussenbux

Technical Architect: Richard Scott Lancelot Ellwood

What we have here then is a most extraordinary situation: a wounded soul, victim of longterm, ongoing child abuse and neglect, who when she looks at the stars "feels as if there could be neither wickedness nor sorrow in the world"! Knowing and feeling, mind and heart seem hopelessly at odds. She asserts that evil and sorrow do not exist in the face of her painful daily experience of both; and she remains convinced that they would be lessened if people would spend more time contemplating the night sky, and thus be "carried out of themselves" into rapture, as she now is.

What we have here then is a most extraordinary situation: a wounded soul, victim of longterm, ongoing child abuse and neglect, who when she looks at the stars "feels as if there could be neither wickedness nor sorrow in the world"! Knowing and feeling, mind and heart seem hopelessly at odds. She asserts that evil and sorrow do not exist in the face of her painful daily experience of both; and she remains convinced that they would be lessened if people would spend more time contemplating the night sky, and thus be "carried out of themselves" into rapture, as she now is. This is a blessing to be cherished. But how could attending to the stars possibly lessen wickedness? Even more, how could there be any reality behind Fanny's feeling that neither wickedness nor sorrow can exist? As we noticed from the close of Austen's scene, the evil incarnate in Mrs. Norris is definitely still there, not at all diminished by the numinous Presence in the starry night, and there is no sign in the story that she would behave with less cruelty even if she attended to it.

This is a blessing to be cherished. But how could attending to the stars possibly lessen wickedness? Even more, how could there be any reality behind Fanny's feeling that neither wickedness nor sorrow can exist? As we noticed from the close of Austen's scene, the evil incarnate in Mrs. Norris is definitely still there, not at all diminished by the numinous Presence in the starry night, and there is no sign in the story that she would behave with less cruelty even if she attended to it.

"I purr, therefore God is."

"I purr, therefore God is." I enjoyed the June PT. I must say that wonderful clip of the lion reunion was so memorable! I'd not seen that before. I also appreciated the message in the editorial. The point that once the thorn is removed from our consciousness we can't bear to participate in violence such as eating meat is tricky, when I think of people who look at pictures of the violence in the flesh industry openly and sincerely, but just aren't moved to the same degree of sadness as we are. It's hard when people just don't feel things, isn't it?

I enjoyed the June PT. I must say that wonderful clip of the lion reunion was so memorable! I'd not seen that before. I also appreciated the message in the editorial. The point that once the thorn is removed from our consciousness we can't bear to participate in violence such as eating meat is tricky, when I think of people who look at pictures of the violence in the flesh industry openly and sincerely, but just aren't moved to the same degree of sadness as we are. It's hard when people just don't feel things, isn't it?

Jane Goodall's Forward to this book is highly encouraging, because she sounds much more strongly pro-vegetarian than she did four years ago. On the other hand, the Introduction by Amy Hatkoff, though generally excellent, has the one statement in the whole book with which I have to disagree: "The Judeo-Christian view holds that only humans were created in God's image and that therefore, the purpose of animals is to be of service to mankind." (Page 16). This is one-sided and misleading. There is a strong and growing pro-animal tradition in both Jewish and Christian thought that holds that animals receive their spirit from God just as humans do, and as such, have a right to life and joy. The view Ms. Hatkoff mentions, though distressingly common in the West, in fact owes more to Aristotle than to the Bible.

Jane Goodall's Forward to this book is highly encouraging, because she sounds much more strongly pro-vegetarian than she did four years ago. On the other hand, the Introduction by Amy Hatkoff, though generally excellent, has the one statement in the whole book with which I have to disagree: "The Judeo-Christian view holds that only humans were created in God's image and that therefore, the purpose of animals is to be of service to mankind." (Page 16). This is one-sided and misleading. There is a strong and growing pro-animal tradition in both Jewish and Christian thought that holds that animals receive their spirit from God just as humans do, and as such, have a right to life and joy. The view Ms. Hatkoff mentions, though distressingly common in the West, in fact owes more to Aristotle than to the Bible. A notable insight from the chapters on sheep and cows: both are much better at distinguishing humans from one another than your average human is in distinguishing a cow from a cow or a sheep from a sheep (although I suspect the animals also have the help of their sense of smell). This superior perceptiveness means they have an intelligence greater than ours in this area. In a story on page 134, some readers of PT will recognize Rambo, the wonderfully altruistic and compassionate ram featured in our Jan. 2009 editorial (See

A notable insight from the chapters on sheep and cows: both are much better at distinguishing humans from one another than your average human is in distinguishing a cow from a cow or a sheep from a sheep (although I suspect the animals also have the help of their sense of smell). This superior perceptiveness means they have an intelligence greater than ours in this area. In a story on page 134, some readers of PT will recognize Rambo, the wonderfully altruistic and compassionate ram featured in our Jan. 2009 editorial (See  Wesley the Owl is the latest in a memorable recent series of books by women of science about their bird-companions, in which science, cohabitation, and in a real sense love-interest combine in an adventure that leaves the reader thinking very differently than before about birds, and perhaps also about humans and their inter-species capabilities. There was, for example, Irene Pepperberg's Alex and Me (see

Wesley the Owl is the latest in a memorable recent series of books by women of science about their bird-companions, in which science, cohabitation, and in a real sense love-interest combine in an adventure that leaves the reader thinking very differently than before about birds, and perhaps also about humans and their inter-species capabilities. There was, for example, Irene Pepperberg's Alex and Me (see  Wesley lived some nineteen years, more than a normal lifespan for his species. There is sadness toward the end; Stacy herself came to suffer from an inoperable brain tumor, nearly fatal until the condition was finally stabilized. Only her deep commitment to Wesley saved her from suicide. It was not long afterwards that the aged bird inevitably declined and died. But, as Stacy makes clear, their love was forever. Indeed, in a few restrained but meaningful passages, one understands that life with Wesley convinced the author of the reality of spirit and God. She also came, by experience, to appreciate the growing belief that telepathic communication can take place between humans and animals.

Wesley lived some nineteen years, more than a normal lifespan for his species. There is sadness toward the end; Stacy herself came to suffer from an inoperable brain tumor, nearly fatal until the condition was finally stabilized. Only her deep commitment to Wesley saved her from suicide. It was not long afterwards that the aged bird inevitably declined and died. But, as Stacy makes clear, their love was forever. Indeed, in a few restrained but meaningful passages, one understands that life with Wesley convinced the author of the reality of spirit and God. She also came, by experience, to appreciate the growing belief that telepathic communication can take place between humans and animals.