Editorial: Avi Kuzi: Compassion in Action

by Benjamin Urrutia

Although there is much controversy about (and in) Israel as a political entity, in one area there is widespread agreement that Israel is a leader, namely in the stands it has taken regarding animals, from whales to geese. In keeping with this admirable tradition, it is appropriate that a particularly valiant defender and rescuer of animals is an Israeli, Avi Kuzi. Now in his early forties, he has spent the last fifteen years working as a full-time rescuer of animals. The fee he charges is 700 new shekels - close to $165, a ridiculously small amount for risking life and limb by, for example, "rappelling down a ten-story elevator shaft to extract a stuck cat."

Avi has been bitten, clawed and kicked many times by the frightened victims he saves, but such experiences have not persuaded him to change his vocation or raise his fees. He has saved thousands of his furry and feathered siblings. Perhaps the most sensational of his exploits was the rescue of a starving and dehydrated camel who was wandering in a desert border zone. This unhappy being was endangered not only by nature, pitiless here, but by past human violence, because the area was planted with land mines. Despite the danger of a deadly explosion and the amount of harm a disturbed camel can inflict, Avi brought the big beast to safety.

Yet perhaps more impressive is his everyday devotion to unwanted animals. As of April 2009 he was living in a "perfectly neat, spotless and odorless" North Tel Aviv apartment, with its windows wide open, in the company of seven cats, four dogs - and zero humans.One of the dogs was scarred by acid in the face. Another one is blind. A third was born without front legs. One of the cats has the same handicap. Three cats are blind. One cat's balance is off. Another lost a leg in an accident. All eleven know they are loved and well-protected by Avi. Like Leonardo Da Vinci, (See PT Issue 23) Avi Kuzi buys caged birds just to set them free.

Though Israel has been the home of such vegetarian teachers as the saintly rabbi/theologian Avraham Kook (see PT Issue 20) and others, Avi is a pioneer who derived his principles from direct spiritual experience rather than from study. When he was still very young, he had a deeply meaningful dream in which he saw a pleasant green valley full of animals, who suddenly became at first white as milk, then red as blood. He interpreted this to mean that milk when consumed by humans is nothing but "white blood," and he became a strict vegan. He carries this conviction to the point of refusing to eat in any restaurant, or to attend any party, that serves dead animals or product stolen from animals. Leather he also rejects; the hiking boots he wears are made of synthetics.

His admirers proclaim him a saint - a rough-and-tumble Francis of Assisi - or a prophet. But an aspect of his activities that many people may object to is diving armed with a knife to cut open fishing nets and set the captive creatures free. Is such an attack on property an act of vandalism, or even violence? Or is it rather the moral equivalent of disabling traps intended to inflict agonizing deaths on foxes and beavers? The difference will probably depend on current public perception. Fishing is still widely seen as an acceptable means of procuring food, whereas trapping fur-bearing animals is increasingly considered heartless pandering to a taste for luxury items. But Avi, of course, is taking the viewpoint of the fish. On another level, he is simultaneously helping to curb the threat posed by (over-) fishing to our planet's health. One immediate advantage--Avi does not need to look for homes for the rescued fish!

(The fish issue makes me wonder: Did Jesus chose at least four of his twelve apostles from the ranks of fishermen because he wanted to get them away from their nets and from the business of killing fish? I am inclined to think that may have been part of his motivation, though there are of course stories, of varying levels of historic probability, of Jesus encouraging fishing as well.)

I am not calling upon anyone to grab a knife and start slashing fishing nets, but we would all do well to imitate Avi Kuzi in his thoroughgoing commitment to a peaceable table, and to putting his unconditional compassion for all animals into action.

Unset Gems

"Do not do unto other beings what would be hateful if done to you. All the rest is dessert. Now go and eat!"--Daniel Brook (with thanks to Rabbi Hillel)

-- contributed by Karen Borch

"You have just dined, and however scrupulously the slaughterhouse is concealed in the graceful distance of miles, there is complicity." — Ralph Waldo Emerson

--Observed on a tee shirt

"People must have renounced, it seems to me, all natural intelligence to dare to advance that animals are but animated machines.... It appears to me, besides, that they can never have observed with attention the character of animals . . . It would be very strange that [animals] should express so well what they could not feel.“

"People must have renounced, it seems to me, all natural intelligence to dare to advance that animals are but animated machines.... It appears to me, besides, that they can never have observed with attention the character of animals . . . It would be very strange that [animals] should express so well what they could not feel.“

~François-Marie Arouet, aka Voltaire (1694 - 1778)

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

"Empires live by numbness. . . . Governments and societies of domination go to great lengths to keep the numbness intact. [The prophet] Jesus penetrates the numbness by his compassion and . . . mak[es] visible the odd abnormality that had become business as usual. Thus compassion . . . is in fact criticism of the system, forces, and ideologies that produce the hurt." -- Walter Brueggeman, The Prophetic Imagination, p. 88-9

News Notes

One of Aesop's fables tells of a terribly thirsty crow who came upon a pitcher with only a little water in it. He couldn't reach the water, but by dropping in pebble after pebble, he finally raised the water level to where he could drink it.

Though Aesop's beasts are usually stand-ins for human beings, this story may be based on observation of crows, who are increasingly getting their due, especially from ornithologists and other bird-watchers, as very intelligent tool-creating birds. British scientists Christopher Bird (no relation) and Nathan J. Emery have offered rooks, relatives of crows, a bottle of water with bugs floating in it below their reach, and piles of pebbles nearby. And the rooks, who are either very creative, read Greek, or have ancestral memories, dropped the pebbles into the bottle until the treat was in reach. Bird's and Emery's findings are published in Current Biology.

Though Aesop's beasts are usually stand-ins for human beings, this story may be based on observation of crows, who are increasingly getting their due, especially from ornithologists and other bird-watchers, as very intelligent tool-creating birds. British scientists Christopher Bird (no relation) and Nathan J. Emery have offered rooks, relatives of crows, a bottle of water with bugs floating in it below their reach, and piles of pebbles nearby. And the rooks, who are either very creative, read Greek, or have ancestral memories, dropped the pebbles into the bottle until the treat was in reach. Bird's and Emery's findings are published in Current Biology.

--Contributed by Benjamin Urrutia

One of our readers informs us that the Florida prison system has reduced its use of flesh and dairy in its menus by the use of textured vegetable protein and soy milk. This change is a cost-cutting measure, not a compassionate one, but it will benefit all concerned.

As members of the Animal Kinship committee are wont to say--"Pick a reason, any reason!" --Editor

Letters

Dear Peaceable Friends,

There will be an update of HIPPO news soon, especially regarding the projects in Uganda and Tanzania. It is sometimes frustrating that people are so slow to adopt what is to us the obviously most compassionate, healthy, efficient, and ecologically sound way of life. But when I remember how things were when I first became veggie back in 1958 I can hardly believe the progress that has been made. I would never have dreamed then that vegetarian 'convenience' foods would be generally available in supermarkets, still less that plant milks would be there on the shelves and now cheaper than cows' milk, which is a real breakthrough I think. Still, now that it is so easy to make the change one wonders why just about everybody doesn't do it.

Do you know of the Vegan Organic Network (VON) here in England? (See VON ) They pioneer and foster vegan organic growing, horticulture and agriculture. This is the logical future. However I must say that in the third world situation we cannot be so purist in our approach to things. Changing the culture of pastoralists for whom animals have meant everything cannot be other than a gradual process. Our emphasis with them cannot be on the cruelty of traditional diet, as this would merely alienate and offend--though of course we certainly don't hide our own principles on this. But introducing the growing and eating of vegetables and pulses has to be approached mainly from a health and sustainability point of view. Everybody is interested in good health, especially in Africa where there is so much ill health and poor nutrition, and getting across the importance and superiority from a health and ecology point of view of plant foods against animal foods is at present the best strategy for us to use . . . . We have to be practical and pragmatic. It is an achievement to see Afars in Ethiopia, and Samburu or Maasai in Kenya, growing and eating vegetable foods at all!

In the longer term we know that vegetarianism is possible and will indeed come to be - in the Millennium of Christ's kingdom if not before. We are blazing a trail that definitely leads towards the Peaceable Kingdom!

Incidentally Hazel and I are very proud to have a Samburu daughter-in-law who has become vegetarian since meeting our son Mark, and we now have a Samburu-English grand daughter of nine months. Left to right, Cynthia, Mark, Angela Nempiris (Samburu for Grace of God), Hazel, and Neville.

Be blessed,

Neville Fowler

HIPPO, "Help International Plant Protein Organization," was founded by Neville, a Welsh agronomist, to foster plant-based agriculture in developing countries, chiefly in Africa. For Neville's Pioneer story, see PT Issue 52 . For more about HIPPO, see PT Issue 17 . The street address there given is no longer valid, but donations may still be sent by PayPal.

Dear Peaceable Friends,

I enjoyed Robert Ellwood's editorial in the Sept. PT on the relevance of veganism to the health care issue. . . . . The unhealthy overweight doctors presenting themselves as healers serve as an apt microcosm of the unhealthy overblown health care industry trying to heal the citizens.

. . . The eradication of animal products from the diets of the world's populations would be perhaps the most important change imaginable. These benefits can be so clearly shown that it is impossible for me not to build up my hopes that this change will see dramatic increase in the future, whether the intent behind it be saving money or saving lives, reducing the suffering of both humanity and animals.

So I hope. So I pray. . . .

--Carl Sheppard

Glimpses of the Peaceable Kingdom

Parrot Strokes Kitten

In two short film clips, a parrot can be seen stroking or grooming a kitten and apparently trying to "baby-sit" her or him, bird-fashion. See

Bird Pets Cat and Bird on Cat .

--Contributed by Fay Elanor Ellwood

Bambi and Thumper

Did you miss this wonderful series of photos by Tanja Askani showing the devoted friendship of a fawn and a rabbit throughout the seasons? See Fawn and Rabbit .

Did you miss this wonderful series of photos by Tanja Askani showing the devoted friendship of a fawn and a rabbit throughout the seasons? See Fawn and Rabbit .

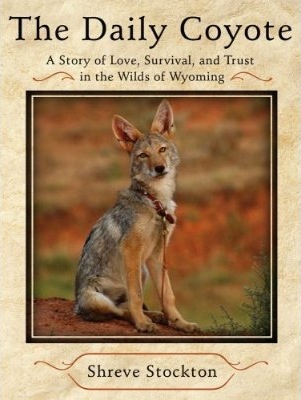

Book Review: The Daily Coyote

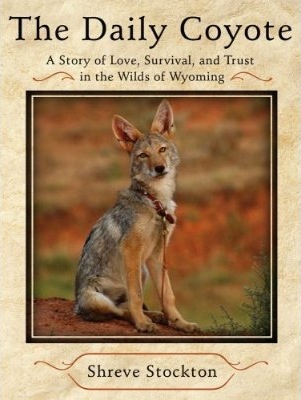

Shreve Stockton. The Daily Coyote: A Story of Love, Survival, and Trust in the Wilds of Wyoming. New York: Simon and Schuster, $23.00. 287 pp. hardcover. 2008.

This is yet another first-person tale of a young woman and her relationship with an animal, following on the heels of Alex and Me, Wesley the Owl, and others that have been reviewed in the pages of The Peaceable Table. The Daily Coyote is different in several ways, however. First of all, the animal is a mammal, not a bird; second, the story takes place in some of the wildest rural country left in the United States, not a city or an academic setting; thirdly, for that very reason it raises profound and disturbing questions about saving and killing, love and death amid the harsh order imposed by nature -- and the harsher one imposed by humans.

This is yet another first-person tale of a young woman and her relationship with an animal, following on the heels of Alex and Me, Wesley the Owl, and others that have been reviewed in the pages of The Peaceable Table. The Daily Coyote is different in several ways, however. First of all, the animal is a mammal, not a bird; second, the story takes place in some of the wildest rural country left in the United States, not a city or an academic setting; thirdly, for that very reason it raises profound and disturbing questions about saving and killing, love and death amid the harsh order imposed by nature -- and the harsher one imposed by humans.

Shreve Stockton had lived most of her life in the city: Seattle, New York, San Francisco. But she was ever an adventurous person. Riding her Vespa motor-scooter back from the Bay to New York, she found herself falling in love with the sparsely-settled but dramatically beautiful land around the Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming, ranching country--which could hardly have been more different, both physically and culturally, from what she had known. Impulsively, she stopped and settled in a tiny town picturesquely called Ten Sleep, forty miles even from a grocery store. (Having lived half of my youth in a larger but comparable town in western Nebraska, not too far from Ten Sleep as driving goes in those wide open spaces, I have some idea what she encountered, but she (and probably many readers) would not know what to expect.)

Before long Shreve met Mike, a kindly, lonely, strong and reliable son of the West, with whom she soon established an increasingly intimate relationship. Mike's job, paid for by both the Federal and state governments, was to kill coyotes -- shooting them from a plane or truck, gassing their pups in the dens, so the animals would not devastate the cattle and sheep on which most local livelihoods depended. He claimed that as a professional he killed them efficiently, and no more than was necessary, but that was his (chosen) job. In rural Wyoming killing is as routine as birthing, and Shreve once said that to call someone a vegetarian (which she is not) in Ten Sleep would be "an insult on a par with calling someone a Republican in Santa Cruz" -- that university town, I suppose, being the epitome of the California "Left Coast."

One day, however, Mike found a helpless 8-day-old pup at the edge of one of the dens, and "something came over him." He scooped the infant animal up in his denim jacket and brought him back to Shreve. She named him Charlie and undertook to raise him, and thereby begins the story. She learned to feed her new baby, to deal with his quirks, to introduce him to her cat Eli (after some testing and sparring, they became close friends), and above all to learn what it means to be companion to a pack predator, a creature ordinarily considered an enemy.

One day, however, Mike found a helpless 8-day-old pup at the edge of one of the dens, and "something came over him." He scooped the infant animal up in his denim jacket and brought him back to Shreve. She named him Charlie and undertook to raise him, and thereby begins the story. She learned to feed her new baby, to deal with his quirks, to introduce him to her cat Eli (after some testing and sparring, they became close friends), and above all to learn what it means to be companion to a pack predator, a creature ordinarily considered an enemy.

Two things made this relationship into a book. One, as a professional-class photographer, Shreve took daily pictures of Charlie; many are found in the book, and truly marvelous illustrations they are. Second, she began an internet site called "The Daily Coyote," in which photos and news of Charlie are posted daily. It has become remarkably popular, and she now maintains herself largely from the $5 monthly she charges for access. The book is essentially an extension of the site.

This volume is engrossing, readable in a day, and well worth the time devoted to it. One could not undertake here to summarize all that happens, except to say that as in any good novel, people change, and Charlie was somehow the catalyst of those changes. Shreve went from city girl to country girl, learning to honor the hard work and awareness of nature in all its moods that it takes to live on the barren high plains. I could not accept the killing part of it as she seems to, though I respect her choice to live close to nature, and value her reminding us nature is not always just a wonderful Disney movie.

Nonetheless, there are questions Shreve and Mike ought to ask themselves and each other. Of course they are hard to ask in an environment where meat and killing are basic to the economy, and even harder where ranching is the culture, and its attendant skills are what give people their sense of self-worth. ("It is hard to make a person understand something when his job depends on his not understanding it. . . . ") This is the land of the legendary cowboys, and there are few places where a colorful past still lives as vibrantly as Wyoming.

What Shreve and Mike fail to ask is whether animal agriculture, and the massive killing that goes with it, is good and necessary in the first place. The environment, both the local soil situation and the global warming threat world-wide, would be better off without it; animals would live more natural lives without it; people would be healthier without animal-based food; many more could be fed on an over-populated planet racked with hunger without so many resources devoted to animal feed. Of course such a change would require considerable adjustment on the part of Shreve and Mike, and of Wyoming -- a place I love -- as a whole. But given the state's fabulous scenery and wonderful wildlife, of which Charlie is only one representative, surely Shreve, at least, could find that her photographic gifts would afford her more than enough for a daily posting and a living, and Mike, given that impulsive act of compassion toward Charlie, would almost surely find he likes animal support and rescue better than killing. And they would not be alone. Compassion for suffering animals flourishes even in Wyoming: near Hartville, southeast of Ten Sleep, is the Kindness Ranch (which I support), a fine facility which specializes in the care of dogs, cats, and horses "retired" from laboratories.

The author shares insights she gained into both human and coyote psychology through her reading and her relationships with Charlie and Mike. By way of the "Dog Whisperer" Cesar Millan, she learned that the four great traits of dogs -- and coyotes -- are honesty, integrity, consistency, and loyalty. She saw them in Charlie, even though, like humans, he had bad days and was not always consistent. The young woman realized her coyote companion could help her work on the same qualities in herself, especially the last two, in which he felt especially deficient. She further saw that Charlie really wanted her to be a strong "pack leader," and not to push the responsibility for decisions onto him, as he seemed to think she tended to do. So she needed to become more assertive to live up to his hopes for her. As for Mike, for years he had been suffering grief for the loss of his daughter in a tragic accident (his wife had long since decamped), and it is clear his relationship to Shreve and to Charlie -- the "enemy" he had once pitied -- helped him finally come to terms with his inner tenderness, feel this grief, and work through it.

An unusual book; a fascinating read. Recommended.

--Robert Ellwood

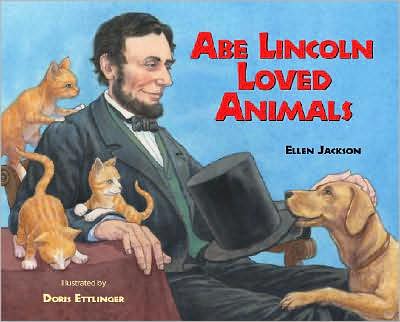

Book Review: Abe Lincoln Loved Animals

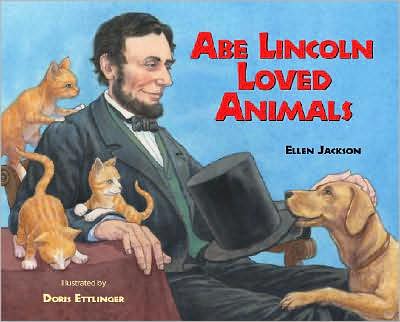

Abe Lincoln Loved Animals. By Ellen Jackson. Illustrated by Doris Ettlinger. Morton Grove, Ill: Albert Whitman & Co.. 2008. No pagination (32 pages). $16.99. Hardcover.

This beautifully illustrated book for children tells the story of the life of Abraham Lincoln from an aspect that I have not seen covered in any other book about this great man: His love of animals. In his youth, he stopped a gang of boys from torturing a turtle. Of course, it helped that he was very tall and strong - but in cases like this, moral and spiritual strength count more than physical. Probably there were other cases when Abe intervened on behalf of oppressed animals, but the stories have not been told because of his modesty (and the shame of the perpetrators). In this book, the only incidents included are those that are firmly documented (documentation covers the last two pages).

Even before the turtle story, we are told - and shown - of the time in his early life when he shot a wild turkey to provide food for the family. He felt such grief and rue over the killing that he made a promise to himself: "I will never hunt large animals again." Of course, it would have been much better if the promise had been: I will never kill or eat any animals, large or small. Indeed, one may hope that such a strong promise will be made by many people, specially children, who contemplate Ettlinger's powerful watercolor of young Abe mourning for the beautiful creature he has just slain.

There is another turkey story later in the book, the one about young, tenderhearted Tad Lincoln persuading his father (easily) to grant a presidential pardon for Jack, a bird who would otherwise have become Thanksgiving dinner. This started the annual tradition of pardoning the White House Thanksgiving turkey (for what crime, one wonders?) Alas, I suspect that another turkey, slaughtered out of sight and out of mind, usually substitutes for the "pardoned" one at the presidential table. However, we may hope that children who read this book will join the movement to spare - in reality, not just as a dramatic gesture - all creatures who would otherwise be killed by humans for self-serving reasons.

Other stories of Abe and the animals are told, mostly about cats and dogs, for both species were much loved by Lincoln. The main text ends with these words: "A Native American legend says that when humans die, they are greeted by all the animals they befriended ... [V]oices from the air, the water, and the land must have welcomed Abraham Lincoln home." This is a beautiful thought, illustrated by a beautiful watercolor painting. It gives me hope that I shall be happily greeted by a multitude of my animal friends.

The book is strongly recommended for everyone, from children learning to read, to old humans nearing the Great Adventure and contemplating what may await us.

-Benjamin Urrutia

Recipes

Happier Black Bean Soup

1 1/2 cups cooked black beans

3

cups water or veggie broth

Medium-to-small potato

2 medium carrots

1 medium onion

2 tsp. Better than Bouillon vegetable bouillon paste, or equivalent cubes

1 large clove garlic

Fresh parsley

Put beans, bouillon paste and broth on to heat. Chop vegetables, add to soup, and cook until tender. Put through blender. Before serving, add finely chopped garlic and stir. Top each bowl with chopped parsley.

This recipe is veganized from one in Joy of Cooking. Taste before serving; if too bland, stir in more bouillon paste. I usually go easy on this ingredient because, though tasty, it contains so much salt.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

Linda's Indian Rice

3/4 cup brown Basmati rice

3/4 cup brown Basmati rice

1 1/2 cups water or veggie broth plus 1 Tbsp

1 onion, chopped

2 tsps. olive oil

3/4 tsp. each of ginger, paprika, salt, cloves, and cinnamon

1 large clove garlic

cilantro

Saute the onion in the oil with the salt and spices in nonstick pan. Add the rice and continue until it is golden. Add water and simmer until it is absorbed. Shortly before removing from flame, add peas. Serve, topping with chopped cilantro.

I confess to adding a tablespoon of soy sauce before serving, which our family likes, though it doubtless ruins the authenticity of the dish.

This recipe is modified from one contributed by Linda Alipuria to A Feast of Friendship, a cookbook produced by the Central America Committee of Orange Grove Friends in 1987 to raise funds to help Latino refugees.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

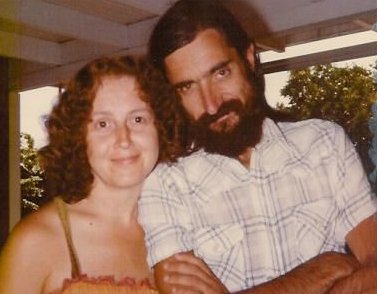

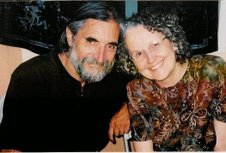

Pioneers: Sherry and Robert Madrone

Like most of us who now dine at the peaceable table, the childhoods of this Quaker couple were in families who took eating animals for granted. Bob was born and raised in San Diego, California, in a family whose diet was pretty standard, supplemented by fish and abalone from the ocean nearby. But potential questions were stirring under the surface of his consciousness. In high school he was intrigued by the lives of famous pacifists such as Bertrand Russell, Gandhi, and Albert Schweitzer. The natural extension of this commitment was their vegetarian diet, a factor that spoke to Bob's heart.

Reading about their lives inspired him to plan a life of service, and after graduating from college he became a social worker. He had not yet tried a nonviolent diet himself, but in 1970, a friend and co-worker who lived with him for several months mentioned that he would like to try vegetarianism. Bob was quite willing, and from that point on, he evolved in the direction of veganism. In those early days he ate a lot of sugar and dairy. He didn’t cook much--mostly mac and cheese when he did bestir himself in the kitchen. His meals were primarily cheese hoagies and crepes from little cafes on the beach, a setup which gave him time to work and surf. Though his main reason for going veg was ethical, he hadn’t yet made the connection regarding dairy and eggs.

Sherry was raised in Idaho on a standard farm diet of meat and potatoes. The violence underlying this typical diet wasn't invisible as it is for most city dwellers; her father went hunting and brought home duck, pheasant, antelope, and deer corpses. Their eggs often revealed bloody streaks or an unborn chick in them; so there was no doubt that their meat was recently a live being.

At the same time, there were positive relations with animals. Ranchers gave the family lambs whose mothers had rejected them (and whom the ranchers would otherwise have killed), and the children bottle-fed these orphans. Sherry participated in a 4-H project, raising a calf whom she named Lady, and sometimes slept with her friend in the barn. When Lady had to get up, she would signal Sherry by licking her ankle. Thanks to these experiences, Sherry became aware that animals had personalities, including feelings of compassion.

But this beginning of awareness did not translate into reluctance to eat animal flesh at that time. (Vegetables were more likely to be a problem for her siblings; the five kids were expected to eat everything on their plates, and couldn’t leave the table until they did. The children developed a system whereby they slipped their vegetables under the table to Sherry, who would eat them so that they could leave.)

The dietary message about meat which Sherry received in childhood was reinforced later in nursing school, where the nutrition classes insisted it was necessary to health. After graduation she went to Hawaii, worked in a Japanese hospital and took Chinese cooking classes in town; her culinary horizons were widening.

Having returned to California in 1969, Sherry participated in the counterculture, including the Peace movement, where she encountered Friends. She also began to meet vegetarians, a popular hippie lifestyle theme in those days. A nonviolent diet was rightly seen as an important element of a commitment to understanding and harmony with the world, rather than the exploitation and violence that was so prevalent. She began  to try new recipes heavy on whole grains and vegetables. A new level was reached in 1972,when she met Bob, who had been vegetarian for two years already. She found that the way to that man’s heart--after two years of sandwiches and macaroni and cheese--was a good vegetarian meal! They soon decided to take a formal course in vegetarian cooking offered by a Seventh Day Adventist woman. The course was primarily vegan, dairy being considered transitional. The “text” was a cookbook called Ten Talents. Under this guidance, they expanded their knowledge and confidence in their choice.

to try new recipes heavy on whole grains and vegetables. A new level was reached in 1972,when she met Bob, who had been vegetarian for two years already. She found that the way to that man’s heart--after two years of sandwiches and macaroni and cheese--was a good vegetarian meal! They soon decided to take a formal course in vegetarian cooking offered by a Seventh Day Adventist woman. The course was primarily vegan, dairy being considered transitional. The “text” was a cookbook called Ten Talents. Under this guidance, they expanded their knowledge and confidence in their choice.

In April 1973 there was a national meat boycott, prompted by rising meat prices, due in part to an agreement Nixon made to ship grain to Russia. Suddenly there were lots of recipes and articles about a vegetarian diet. Mainstream interest at last!

The next year they moved from San Diego to Sonoma County in northern California, going back to the land. They bought thirty-seven acres of forestland and built a little cabin from recycled barn wood, using only hand tools. Their lifestyle, and certainly their diet, was very simple. They bought big bags of oatmeal, brown rice, and soybeans, cooked on a little camp stove, and hauled water from a spring to wash their dishes. They didn’t have a refrigerator or any electricity--but then there was no need to preserve meat and dairy. They kept their veggies in a vase, like a bouquet, on their tiny table. By this time, they ate dairy only at potlucks or in other homes. During this time, Bob studied at Sonoma State College, getting an M.A. in Environmental Studies; after that, he worked in Sonoma County Parks, later becoming a park ranger. Sherry joined a midwifery study group and was a midwife for sixteen years, attending births of over three hundred babies. This added another aspect to her awareness of the sacredness of all life.

In 1978, disaster struck in Bob and Sherry's lives. A forest fire, sparked by human error, consumed their home and belongings, orchard, and everything on the land. Through the kindness of others, they were housed. Living closer to town then, they began to explore religious organizations, joining Redwood Forest Quaker Meeting in Santa Rosa in 1979. Three or four years later they transferred their membership to the new Apple Seed Meeting in Sebastopol, where they continue to be very active.

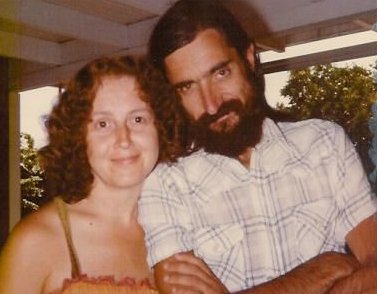

Soon after losing their house and other property, they became pregnant. This gave them reason to look to the future and not dwell on their loss; correspondingly, they built a new home on their land. Their son, Christian Madrone, was born at home in 1979. Sherry and Bob also took the name Madrone, derived from a flowering tree found along much of the northern and central Pacific coastline (see photo at right.) There were gloomy predictions that their child’s growth would be stunted without meat, but they held to their convictions in rearing him. (He’s now 6’3”, makes his living as a restaurant manager, and is still vegetarian.)

Soon after losing their house and other property, they became pregnant. This gave them reason to look to the future and not dwell on their loss; correspondingly, they built a new home on their land. Their son, Christian Madrone, was born at home in 1979. Sherry and Bob also took the name Madrone, derived from a flowering tree found along much of the northern and central Pacific coastline (see photo at right.) There were gloomy predictions that their child’s growth would be stunted without meat, but they held to their convictions in rearing him. (He’s now 6’3”, makes his living as a restaurant manager, and is still vegetarian.)

As they became more aware over the years, they gave up all dairy, eggs, white sugar, honey and leather until they were totally vegan by about 1995. They realized the many benefits to the earth, compassion for animals, hungry peoples, and their own health.

It’s a lot easier these days to find books, articles, packaged foods and other vegan products than it was in the 1970s. Having become so used to their vegan way of life after all these years, they don’t have to consult cookbooks except for special occasions. Whatever is in the pantry, icebox, orchard or garden largely determines their meals. They shop at a great natural foods store about eighteen miles away to restock the basics. (It’s appropriately called Food for Humans!) Their meals are still simple, but have much more  variety than in those early days. Even on their limited income, they eat very well. Beautiful woods surround them again, and the wildlife thank them every day.

variety than in those early days. Even on their limited income, they eat very well. Beautiful woods surround them again, and the wildlife thank them every day.

Bob is now 67 and Sherry is 65. They still live in their off-the-grid home in Sonoma County. And yes, Bob still surfs!

--Robert and Sherry Madrone

Poetry and Song:

Thanks Be to God

Thanks be to God for roses red,

For homes and hearths and daily bread

For all the worlds thy hands have wrought--

Thanks be to God.

Thanks be to God for surf on seas,

Thanks be to God for surf on seas,

For trilling finches, flowering trees,

For freshness that cannot be bought--

Thanks be to God.

Thanks be to God for prophet-truth,

For hands that work for right and ruth,

For every healing act and thought,

Thanks be to God.

Thanks be to God who guides our days

From loss to Love, from pain to praise

For Thee, the Gift of gifts unsought--

Thanks be to God!

--Sr. Faith Bowman (Stanza 1 Anonymous)

To be sung to the music of "Thanks Be to God" by Stanley Dickson

(May Hannah Dickson Brahe)

Merlin and the Gleam

. . . Not of the sunlight,

Not of the moonlight,

Not of the starlight!

O young Mariner,

Down to the haven,

Call your companions,

Launch your vessel,

And crowd your canvas,

And, ere it vanishes

Over the margin,

After it, follow it,

Follow The Gleam.

--Alfred Tennyson

The Peaceable Table is

a project of the Animal Kinship Committee of Orange Grove Friends Meeting, Pasadena, California. It is intended to resume the witness of that excellent vehicle of the Friends

Vegetarian Society of North America, The Friendly

Vegetarian, which appeared quarterly between 1982 and

1995. Following its example, and sometimes borrowing from its

treasures, we publish articles for toe-in-the-water

vegetarians as well as long-term ones.

The journal is intended to be

interactive; contributions, including illustrations, are

invited for the next issue. Deadline for the Nov. issue

will be Oct. 28, 2009. Send to graciafay@gmail.com

or 10 Krotona Hill, Ojai, CA 93023. We operate primarily

online in order to conserve trees and labor, but hard copy

is available for interested persons who are not online.

The latter are asked, if their funds permit, to donate $12 (USD) per year. Other

donations to offset the cost of advertising (in The Christian Century) are welcome.

Website: www.vegetarianfriends.net

Editor: Gracia Fay Ellwood

Book and Film Reviewers: Benjamin Urrutia & Robert Ellwood

Recipe Editor: Angela Suarez

NewsNotes Contributors: Lorena Mucke and Marian Hussenbux

Technical Architect: Richard Scott Lancelot Ellwood

"People must have renounced, it seems to me, all natural intelligence to dare to advance that animals are but animated machines.... It appears to me, besides, that they can never have observed with attention the character of animals . . . It would be very strange that [animals] should express so well what they could not feel.“

"People must have renounced, it seems to me, all natural intelligence to dare to advance that animals are but animated machines.... It appears to me, besides, that they can never have observed with attention the character of animals . . . It would be very strange that [animals] should express so well what they could not feel.“

Though Aesop's beasts are usually stand-ins for human beings, this story may be based on observation of crows, who are increasingly getting their due, especially from ornithologists and other bird-watchers, as very intelligent tool-creating birds. British scientists Christopher Bird (no relation) and Nathan J. Emery have offered rooks, relatives of crows, a bottle of water with bugs floating in it below their reach, and piles of pebbles nearby. And the rooks, who are either very creative, read Greek, or have ancestral memories, dropped the pebbles into the bottle until the treat was in reach. Bird's and Emery's findings are published in Current Biology.

Though Aesop's beasts are usually stand-ins for human beings, this story may be based on observation of crows, who are increasingly getting their due, especially from ornithologists and other bird-watchers, as very intelligent tool-creating birds. British scientists Christopher Bird (no relation) and Nathan J. Emery have offered rooks, relatives of crows, a bottle of water with bugs floating in it below their reach, and piles of pebbles nearby. And the rooks, who are either very creative, read Greek, or have ancestral memories, dropped the pebbles into the bottle until the treat was in reach. Bird's and Emery's findings are published in Current Biology.

Did you miss this wonderful series of photos by Tanja Askani showing the devoted friendship of a fawn and a rabbit throughout the seasons? See

Did you miss this wonderful series of photos by Tanja Askani showing the devoted friendship of a fawn and a rabbit throughout the seasons? See  This is yet another first-person tale of a young woman and her relationship with an animal, following on the heels of Alex and Me, Wesley the Owl, and others that have been reviewed in the pages of The Peaceable Table. The Daily Coyote is different in several ways, however. First of all, the animal is a mammal, not a bird; second, the story takes place in some of the wildest rural country left in the United States, not a city or an academic setting; thirdly, for that very reason it raises profound and disturbing questions about saving and killing, love and death amid the harsh order imposed by nature -- and the harsher one imposed by humans.

This is yet another first-person tale of a young woman and her relationship with an animal, following on the heels of Alex and Me, Wesley the Owl, and others that have been reviewed in the pages of The Peaceable Table. The Daily Coyote is different in several ways, however. First of all, the animal is a mammal, not a bird; second, the story takes place in some of the wildest rural country left in the United States, not a city or an academic setting; thirdly, for that very reason it raises profound and disturbing questions about saving and killing, love and death amid the harsh order imposed by nature -- and the harsher one imposed by humans. One day, however, Mike found a helpless 8-day-old pup at the edge of one of the dens, and "something came over him." He scooped the infant animal up in his denim jacket and brought him back to Shreve. She named him Charlie and undertook to raise him, and thereby begins the story. She learned to feed her new baby, to deal with his quirks, to introduce him to her cat Eli (after some testing and sparring, they became close friends), and above all to learn what it means to be companion to a pack predator, a creature ordinarily considered an enemy.

One day, however, Mike found a helpless 8-day-old pup at the edge of one of the dens, and "something came over him." He scooped the infant animal up in his denim jacket and brought him back to Shreve. She named him Charlie and undertook to raise him, and thereby begins the story. She learned to feed her new baby, to deal with his quirks, to introduce him to her cat Eli (after some testing and sparring, they became close friends), and above all to learn what it means to be companion to a pack predator, a creature ordinarily considered an enemy.

3/4 cup brown Basmati rice

3/4 cup brown Basmati rice

to try new recipes heavy on whole grains and vegetables. A new level was reached in 1972,when she met Bob, who had been vegetarian for two years already. She found that the way to that man’s heart--after two years of sandwiches and macaroni and cheese--was a good vegetarian meal! They soon decided to take a formal course in vegetarian cooking offered by a Seventh Day Adventist woman. The course was primarily vegan, dairy being considered transitional. The “text” was a cookbook called Ten Talents. Under this guidance, they expanded their knowledge and confidence in their choice.

to try new recipes heavy on whole grains and vegetables. A new level was reached in 1972,when she met Bob, who had been vegetarian for two years already. She found that the way to that man’s heart--after two years of sandwiches and macaroni and cheese--was a good vegetarian meal! They soon decided to take a formal course in vegetarian cooking offered by a Seventh Day Adventist woman. The course was primarily vegan, dairy being considered transitional. The “text” was a cookbook called Ten Talents. Under this guidance, they expanded their knowledge and confidence in their choice.  Soon after losing their house and other property, they became pregnant. This gave them reason to look to the future and not dwell on their loss; correspondingly, they built a new home on their land. Their son, Christian Madrone, was born at home in 1979. Sherry and Bob also took the name Madrone, derived from a flowering tree found along much of the northern and central Pacific coastline (see photo at right.) There were gloomy predictions that their child’s growth would be stunted without meat, but they held to their convictions in rearing him. (He’s now 6’3”, makes his living as a restaurant manager, and is still vegetarian.)

Soon after losing their house and other property, they became pregnant. This gave them reason to look to the future and not dwell on their loss; correspondingly, they built a new home on their land. Their son, Christian Madrone, was born at home in 1979. Sherry and Bob also took the name Madrone, derived from a flowering tree found along much of the northern and central Pacific coastline (see photo at right.) There were gloomy predictions that their child’s growth would be stunted without meat, but they held to their convictions in rearing him. (He’s now 6’3”, makes his living as a restaurant manager, and is still vegetarian.)  variety than in those early days. Even on their limited income, they eat very well. Beautiful woods surround them again, and the wildlife thank them every day.

variety than in those early days. Even on their limited income, they eat very well. Beautiful woods surround them again, and the wildlife thank them every day.  Thanks be to God for surf on seas,

Thanks be to God for surf on seas,