Friends Without Boundaries

We,

the minority who are committed to Peace / Nonviolence, have, in the

past almost always assumed an uncrossable boundary between people and

the nonhuman world. It was only human beings, bearers of the divine spark,

to whom we refused all violence. In this regard we were absorbing the

commonly-held values of Western culture, in which virtually anything

nonhuman on the planet was either a "resource," or property, or

potential property. (Of course, prior to the nineteenth century, even

certain people were assumed to be property.)

We,

the minority who are committed to Peace / Nonviolence, have, in the

past almost always assumed an uncrossable boundary between people and

the nonhuman world. It was only human beings, bearers of the divine spark,

to whom we refused all violence. In this regard we were absorbing the

commonly-held values of Western culture, in which virtually anything

nonhuman on the planet was either a "resource," or property, or

potential property. (Of course, prior to the nineteenth century, even

certain people were assumed to be property.)

Increasingly, in the last twenty-five and more years, this boundary is being challenged by environmentalists, animal activists, and mystics. The message is that human beings are not the lords of creation, looking down on it in splendid isolation; we are deeply intertwined with its life at every level. As St. Francis said, all things in creation are our sisters and brothers.

This huge expansion of our spiritual family complicates already difficult moral issues. There are large areas on which all creation-loving people can agree: the uncontrolled bulldozing and overgrazing of wild places, the dumping of toxins into streams, the slathering of pesticides over vast tracts of earth--these and other practices of industry, construction and agribusiness are clearly violent assaults on our sister the earth, and on our individual sisters and brothers. But we human beings must eat; we need houses to live in; we need everything from paper to metals to carry on our daily life in society. Certainly we need considerably less of everything than has been assumed in our society, but we still need resources.

What are the implications for our daily life of the fact that all other beings are our kin?

Psychically open people sometimes speak of perceiving other dimensions of life in flowers and trees, even in mountains or lakes. Some ancient peoples interpreted these intuitions as individual spirits, naiads and dryads and devas; unitive mystics may experience them as God's glory permeating all things, or as Godself, asleep in all things, beginning to awaken in various ways. If so--and there is every reason to take such intuitions seriously--does that mean that whenever we destroy any life we attack the Divine? Is every individual tree chopped down, every carrot uprooted, every calf whose throat is cut, every whitefly egg obliterated--are all equally victims of violence?

We

can find help in this sensitive issue by the obvious fact that degrees

of consciousness vary greatly among nonhuman beings. The cabbage may

have a sense of distress at being cut, but it does not have a central

nervous system which would send it signals of agony. Fish do have a

central nervous system, and almost surely are in pain when hooked and

pulled out to suffocate. But most species of fish do not have the

ability to become attached to mate or offspring, like e.g., the wild

goose or the cow, for whom separation or bereavement are likely to lead

to cries of anguish or pining away. Primates not only have capacities

for love and friendship (individuals have even fostered orphans), some

of them have a simple language, a set of signals. In contrast, there

are severely mentally deficient human beings who are apparently

incapable of language, and sociopathic human beings who seem unable to

love or even to have an elementary sense of kinship with other persons.

The fact that in so many "domesticated" and other higher animals we

find so much we consider essentially human calls the exploitative

practices of our culture into sharp question. Furthermore, there is

increasing evidence that the less meat and other animal products a

population eats (other things being equal), the healthier it is. We do

not need meat. For us, especially in our culture of abundance, to kill animals and eat them is unnecessary violence.

We

can find help in this sensitive issue by the obvious fact that degrees

of consciousness vary greatly among nonhuman beings. The cabbage may

have a sense of distress at being cut, but it does not have a central

nervous system which would send it signals of agony. Fish do have a

central nervous system, and almost surely are in pain when hooked and

pulled out to suffocate. But most species of fish do not have the

ability to become attached to mate or offspring, like e.g., the wild

goose or the cow, for whom separation or bereavement are likely to lead

to cries of anguish or pining away. Primates not only have capacities

for love and friendship (individuals have even fostered orphans), some

of them have a simple language, a set of signals. In contrast, there

are severely mentally deficient human beings who are apparently

incapable of language, and sociopathic human beings who seem unable to

love or even to have an elementary sense of kinship with other persons.

The fact that in so many "domesticated" and other higher animals we

find so much we consider essentially human calls the exploitative

practices of our culture into sharp question. Furthermore, there is

increasing evidence that the less meat and other animal products a

population eats (other things being equal), the healthier it is. We do

not need meat. For us, especially in our culture of abundance, to kill animals and eat them is unnecessary violence.

The point is that the long-assumed boundary between people and all animals, which justified the idea that we could make them into property against their will, simply does not exist outside of our minds. What we find instead is a long gradient. We are used to a separate set of terms for subjugating animals: people are enslaved, animals are confined or domesticated; people are murdered, animals are slaughtered. Many people justify this system by the fact that we've always done these things, but in the past, the same argument was used to justify human slavery. It won't do.

These challenges to the language may create discomfort, even anger, but they seldom seem to bring real dialogue, even among Friends. Those who disagree with this issue usually talk past one another. But real dialogue is much needed. The reasons for clinging to our belief that we humans are a separate moral category are complex: perhaps a one-up-one-down view of the world (needing to have beings to look down on in order to feel valuable), or resistance to seeing ourselves as complicit in terrible evils, or discomfort at the idea of so great a change in worldview, or just unwillingness to exchange favorite entrees for the new and unknown.

Speciesism, like racism and sexism, limits our sense of deep community to those beings who look like us. It gives a cosier world, but the massive and unnecessary violence that it justifies brings its own retributions. As Chief Seattle is reputed to have said, what happens to the beasts happens to us all. As a general principle, let us respect all things, all beings as far as possible; let us leave the wayside flower unpicked, the column of ants to labor along the path in peace. When we must take other forms of life to support our own, like primal peoples we can apologize to the spirits of the plants and places which have been destroyed. Since there is so much habitat and creature destruction to make way for our cities and freeways and crops, none of us can take refuge in innocence or self-righteousness; we all have apologies to make. If we are willing to undergo the pain of change and growth, we will find that our circle of friendship expands and our lives grow richer.

They love the country, and none else, who seek

They love the country, and none else, who seek

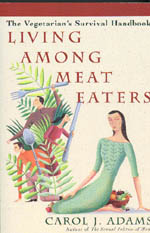

Feminist theologian and activist Carol J. Adams, author of

The Sexual Politics of Meat and other books, has written a

compelling guidebook for vegetarians. Living Among Meat

Eaters is a compassionate and reader-friendly guide for both new

and experienced vegetarians in a culture dominated by people who eat

meat. Adams opens her book with lines from anti-vegetarian signs and

bumper stickers, followed by quotations from vegetarians recounting

unfriendly receptions. The series of such lists at the beginning of

the book works well to draw the reader into the book, as he or she is

likely to identify with some if not many of the experiences of their

fellow vegetarians.

Feminist theologian and activist Carol J. Adams, author of

The Sexual Politics of Meat and other books, has written a

compelling guidebook for vegetarians. Living Among Meat

Eaters is a compassionate and reader-friendly guide for both new

and experienced vegetarians in a culture dominated by people who eat

meat. Adams opens her book with lines from anti-vegetarian signs and

bumper stickers, followed by quotations from vegetarians recounting

unfriendly receptions. The series of such lists at the beginning of

the book works well to draw the reader into the book, as he or she is

likely to identify with some if not many of the experiences of their

fellow vegetarians.