Editorial: The Sins of the Fathers:

The Threat of Deadly Influenza

In the fall of 1918, during the most lethal pandemic in history, there were children in the United States who jumped rope to a ditty that ran

I had a little bird,

Her name was Enza;

I opened a window,

And In-Flew-Enza.

At that time, no one knew what was causing the deadly disease bringing death to many millions across the world who contracted it; the virus would not be identified until the 1930s. But the little scrap of doggerel was more meaningful than anyone then knew. The original source of the 1918 plague WAS birds--not little ones flying through windows, but birds kept in pens to be killed and eaten.

Original Sin, Actual Sin

Influenza is thought to have entered human experience about 4500 years ago, when the Chinese first domesticated wild ducks, and to have become a seasonal problem for us since then. "Domesticated," from the Latin domus, house, implies that the animal is taken into the dwelling, i.e., has become an animal companion; the word has positive, benign associations. Of course, the vast majority of "domesticated" animals are nothing of the sort: they are kept in confinement to be exploited for clothing or food or labor or entertainment. From their point of view, they are slaves, and all humans who profit from them are slave traffickers, slave owners, killers, or receivers of bloodstained stolen goods--i.e., deliberate or inadvertent perpetrators of crimes. Not so benign.(See PT 31, April 2007).

The virus had a comfortable, stable relationship with the duck nation: living in their gut, being excreted in the water, and taken in again on their food. As with various other animal nations (such as certain African apes carrying the precursor of AIDS virus, and apparently Ebola), in its original form this duck virus does its host no harm. But when an alien species invades the ducks' territory, capturing, breeding, and/or killing them, the virus may attack the invaders. Many emerging viruses threatening humans nowadays are zoonotic, i.e. crossed over from such animals.

In the past, when humans contracted the influenza virus directly from "their" ducks, the result was only a mild case of pinkeye. But when the duck slaves were confined in close proximity with chicken and pig slaves (sometimes vertically over each other), and the virus passed to the chickens or pigs, it found itself in a hostile environment. It began to mutate in self-defense, and eventually turned deadly.

Influenza viruses are made up of RNA, not DNA, and have no "spell-check" to catch mistakes when they reproduce. They reproduce sloppily, making scads of mistakes, and thus mutate at an incredibly rapid rate. (This is why specific vaccines soon lose their effectiveness.) They also "reassort," trade genes with viruses from other species. For a major human pandemic, three things are necessary: A. The virus must emerge from the animal world new or in a new form, such that humans have no immunity to it. B. It must turn deadly to humans. C. It must mutate/reassort into a form such that it is easily transmitted from person to person via miniscule droplets spread via touched surfaces, and airborne by talking, coughing, and sneezing.

Pale Horse, Pale Rider : H5N1

In 1997, the most lethal form of influenza ever known, H5N1, emerged in Hong Kong, and infected a small number of people who had been in direct contact with chickens. It was temporarily contained by a bloody massacre of all the chickens in the area. Since then it has appeared, with sub- variations, in flocks of bird slaves across Europe and south Asia, and in most cases, was temporarily contained by a mass killing. The virus has even moved back to wild waterfowl, become benign to some of them, and thus proceeded to migrate across the world. It is loose among birds in thirty countries of the Eastern Hemisphere. As of November 2007, over two hundred people, most of whom had direct contact with birds, have died from it: about 60% of those who were known to be infected. (Compare the 1918 'flu, which killed between 5% and 20% of those infected, adding up to between 50 and 100 million people worldwide.)

variations, in flocks of bird slaves across Europe and south Asia, and in most cases, was temporarily contained by a mass killing. The virus has even moved back to wild waterfowl, become benign to some of them, and thus proceeded to migrate across the world. It is loose among birds in thirty countries of the Eastern Hemisphere. As of November 2007, over two hundred people, most of whom had direct contact with birds, have died from it: about 60% of those who were known to be infected. (Compare the 1918 'flu, which killed between 5% and 20% of those infected, adding up to between 50 and 100 million people worldwide.)

H5N1 has not yet mutated into airborne form, though there seem to have been many opportunities. Most of the various factors involved in the mutation process are abundantly provided in the lucrative animal-prison system entrenched, by means of political cronyism, in the United States, Thailand, and other countries. Bird slaves are jammed together, highly stressed, forced to grow so fast their immune systems are badly compromised, their feces (infected with various kinds of viruses) building up under them, foul damp air circulating and recirculating through the buildings where virus-terminating fresh air and sunlight never enter. Free-range bird slaves are also vulnerable, especially when wildfowl come nearby. When the birds are shipped to killing houses, the stress of transport causes viral reproduction to accelerate markedly. The rapid killing processes result in internal feces being dissolved in the scalding and cold baths, and thus spread over and throughout the severed corpses.

"Safe Handling"

When cooked to appropriate temperature, the various viruses (including not only a potentially mutated H5N1 but salmonella, e. coli, campylobacter, etc.) are killed. But, as a journalist has pointed out, well-cooked s___ is still s___--a useful gross-out point in alerting consumers to what is really going on! Before any amount of cooking, viruses have multiple opportunities to lodge on hands that pick up the sealed packages, on the pieces, on cutting boards, salad vegetables, cleaning cloths, and the like. Refrigeration and freezing even prolong the life of the most lethal hitchhiker, the potentially mutated H5N1 virus. The "safe-handling" instruction card in each package means, in fact, that the contents are dangerous. The only really safe way of dealing with commercial eggs and bird corpses is to boycott them.

Reining In the Pale Horse?

Vaccines will probably not be available on mass levels until six months or more into a pandemic. Because they take time to produce, and are ordinarily not as lucrative as products like Viagra, the big pharmaceuticals have little interest. How about antiviral drugs like "Tamiflu"? This prescription course of ten pills does slow down the proliferation of 'flu viruses, giving the body a much better chance to resist the invader. (At $200 a course, it is obviously tailor-made for the world's millions of poor.) A single pharmaceutical giant, Roche, which owns the patent to Tamiflu, produces it in a single factory in Switzerland (a second is now being built in the US) and threatens with legal action third-world governments who want to make the drug. Some countries like France and England have Tamiflu stockpiles for about 25% of their population. Because the Bush administration ignored scientists' warnings and delayed to place its orders, we in the US are about 40th on the international waiting list; as of mid-2006 we had enough Tamiflu for roughly 2% of our population. There is another potentially helpful antiviral, "Relenza," but it must be inhaled, and inhalers will probably be as scarce as the drug in a pandemic.

Some critical voices (few of them virologists) are claiming that since the H5N1 has not in ten years taken that last deadly step into airborne form, it probably has some Factor X preventing such a development. So why worry? But causes for worry remain. Sub-subtypes of the virus H1N1 were apparently circulating for about eighteen years before one went deadly in 1918 and learned to fly. There are also indications that the H7 or H9 subtypes might turn lethal to humans and go airborne. Most knowledgeable public health authorities consider a pandemic inevitable. What remains uncertain is: will it happen in a week, or in a decade? How severe will it be? How long will it last?

A worst-case scenario would have two billion sick and a billion dying, transportation stopped, food markets empty, electricity and water service halted, panic, violence--in short, civilization a shambles, every major city a post-Katrina chaos particularly for the poor. A lesser attack might resemble the autumn of 1918: in the epicenter in west and central India up to half the population (especially the poor) died of plague and famine, while other areas like New York City reached the brink of breakdown, but social order did survive because the pandemic receded just in time.

Hope is the Thing with Feathers

In any case, one of the most hopeful factors in this gloom-and-doom-laden prospect is the fact that it has not happened yet; we can pray, and we can prepare. We are far from helpless. Panic buying is a bad idea, but we can begin to stockpile slowly, adding more imperishable foods and essential supplies and gallons of water week by week. Online sources such as www.fluwikie.com/ pmwiki.php? n=Consequences.Prevention can provide guidance, as can books like those referenced below. Practicing basic hygiene will also make a major difference: e.g., covering coughs or sneezes by burying your face in the crook of your arm; washing hands thoroughly and frequently; avoiding touching eyes, nose, and mouth; adding bleach to dish and laundry water; boiling drinking water, and the like. Learning to care for persons not desperately ill can also be lifesaving. And, of course, being informed and prepared also serves to reduce fear.

Psychological and spiritual preparation is equally important. How does one deal with chronic fear? with acute fear? How does one cultivate the perfect love that, in the words of I John 4:18, casts out fear? Practically, how does one balance self-care and service? Certainly those who listen closely to the Spirit, spending daily time in prayer and/or meditation, will be in the best position to find answers to ultimate questions, to find God in dark times and live out God's love. Some may find a new relevance in the prayer taught by Jesus to his followers, who lived under a somewhat comparable shadow of hunger, illness, and (imperial) violence: "Father [Mother], May your rule of justice come. May your loving will be done on earth as in heaven. Give us the food we need for today. Forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us. Do not bring us to the test, but deliver us from evil."

"Hope" is the thing with feathers—

That perches in the soul—

And sings the tune without the words—

And never stops—at all . . . .

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

Based on Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching by Michael Greger,

The Monster at Our Door by Mike Davis, The Bird Flu Preparedness Planner by Grattan Woodson, The Great Influenza by John M. Barry,

and online sources. Poem stanza by Emily Dickinson.

Gems

Out of the earth

I sing for them,

a Horse nation . . .

I sing for them,

The animals.

--Teton Sioux Chant

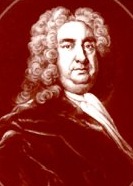

From The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D.:

I never shall forget the indulgence with which he treated Hodge, his cat: for whom he himself used to go out and buy oysters, lest the servants having that trouble should take a dislike to the poor creature. I am, unluckily, one of those who have an antipathy to a cat, so that I am uneasy when in the room with one; and I own, I frequently suffered a good deal from the presence of this same Hodge. I recollect him one day scrambling up Dr. Johnson's breast, apparently with much satisfaction, while my friend smiling and half-whistling, rubbed down his back, and pulled him by the tail; and when I observed he was a fine cat, saying, 'Why yes, Sir, but I have had cats whom I liked better than this;' and then as if perceiving Hodge to be out of countenance, adding, 'but he is a very fine cat, a very fine cat indeed.'

James Boswell, 1740-1795

Book Review: The Great Cat and 100 Cats Who Changed Civilization

Fragos, Emily, ed., The Great Cat: Poems about Cats. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. Everyman's Library Pocket Poets Series. 256 pp. $12.50 hardcover.

Fragos, Emily, ed., The Great Cat: Poems about Cats. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. Everyman's Library Pocket Poets Series. 256 pp. $12.50 hardcover.

Stall, Sam, 100 Cats Who Changed Civilization. Philadelphia: Quirk Books, 2007. 176 pp. $14.95 hardcover.

These two pocket-size volumes should appeal to every cat lover. Each contains poems or anecdotes taking only a page or two, and so would be easy to read on a bus or plane, or at odd moments. But as one does so, one will come more and more to appreciate the strange roles these enigmatic creatures have played in human life, and the passionate responses they have evoked in song and story.

The Great Cat offers verse on the subject by authors as diverse as John Keats, Christina Rosetti, J.R.R. Tolkien, e. e. cummings, Dr Seuss, and Ogden Nash, though oddly enough T. S. Eliot is not included. The poems are sufficient to establish the incredible range of responses felines have evoked in humans: they are at once cute, amusing, mysterious, exasperating, and poignantly evoked after death.

The cats whose tales are collected in 100 Cats Who Changed Civilization, while they may not quite live up to that billing, were certainly unforgettable and made a difference in some way. Here we have Muezza, the Prophet Muhammad's beloved feline companion, whom he often held in his arms while preaching. We salute Oscar, the World War II ship's cat who remarkably survived the sinking of the famous German battleship Bismarck, and then two British warships in succession which went down from under him, before being retired by the Royal Navy (perhaps with some anxiety), to an old-sailors' home. Here, with at least some of his nine lives apparently still available, Oscar lived for another fifteen considerably more peaceful years. There is Pulcinella, whose keyboard ramble suggested the basic melody of a fugue to the composer Domenico Scarlatti; there is Lewis, the attack cat dubbed the "Terrorist of Sunset Circle," finally slapped with an indoors-only restraining order. And many others: the cat who could use a phone to dial 911, the one who accompanied Shackleton to Antarctica, the one who brought food to a prisoner, the one who carried messages in embattled Stalingrad, the one who inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe. Some accounts are humorous, some heartrending, some awesome, but nearly all will remain in one's mind, continually reminding one how remarkable these creatures are.

Books like these, though compact and occasional, are important reads for those concerned with animal defense. They remind us that animals like cats are complete in themselves; they can interact with us, but it is in their own way; that is why they call forth such diverse responses and so often do the unexpected. They are not appendages to humans; they are, at best, companions on the way as we pass together through this complex and diverse world.

--Robert Ellwood

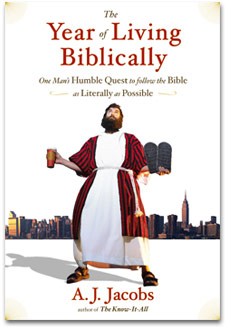

Book Review: The Year of Living Biblically

Jacobs, A.J. The Year of Living Biblically: One Man's Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007. 368 pages, hardcover. $25.00.

A.J. Jacobs, an agnostic of secular Jewish background, a bestselling author and an editor for Esquire magazine, decided to take the Bible seriously: not just read it, but actually obey all the commands and injunctions in both Testaments for a year. His main motivations were to understand religion better; to use the experiment as a basis for writing another funny, far-out book; and to do some genuine spiritual seeking. He also intended to show that Jewish and Christian fundamentalists are not as literalistic as they claim (they all pick and choose) and that biblical literalism is unworkable. He succeeds admirably in these aims. The book has even been optioned for a movie.

A.J. Jacobs, an agnostic of secular Jewish background, a bestselling author and an editor for Esquire magazine, decided to take the Bible seriously: not just read it, but actually obey all the commands and injunctions in both Testaments for a year. His main motivations were to understand religion better; to use the experiment as a basis for writing another funny, far-out book; and to do some genuine spiritual seeking. He also intended to show that Jewish and Christian fundamentalists are not as literalistic as they claim (they all pick and choose) and that biblical literalism is unworkable. He succeeds admirably in these aims. The book has even been optioned for a movie.

The style is delightful; for example, he reports how friends, supposedly entering into the spirit of his experiment , begin their e-letters with waggeries such as "Give ear, O Jacobs!" He responds in kind, while admitting honestly that King-James-Bible language isn't really necessary to what he is doing.

In the course of his year he visited groups such as the Amish who also intend a biblical life, to find out how they did it. One of the facts that came out of his dialogue with them is that "Ninety percent of the horses the Amish have were once racehorses (p. 33)." The Amish are thus saving these beautiful beasts from slaughter. (Since they, unlike most of the world, also have an ecologically sustainable lifestyle, it is cheering to learn that the US-American Amish population has doubled in the last twenty years, now standing at 200,000.)

On page 110 we meet A.J.'s vegan aunt Marti. (For an index of her achievements, Google "Marti Kheel".) This interesting relative admonishes him to avoid using the word "sacred," because it comes from the same root as sacrifice, as in the blood sacrifice of animals. Likewise with the word "bless," because that comes from the Anglo-Saxon bletsia, "to consecrate with blood." One could substitute "benediction" (beneficent saying), but the original meaning of a term's root is not necessarily its present meaning. The sacred does not necessarily involve a sacrifice, and not all sacrifices require the killing of animals (or even involve animals).

In any case, Jacobs does not follow the spirit of his aunt's admonitions, but feels obligated to come as close as possible to the biblical requirements for sacrificing an animal. He carries out a ritual--of dubious orthodoxy--of having a chicken ritually slaughtered. While not technically a sacrifice, it is close enough. The experience was distressing, even frightening--not only for the poor chicken, but for Jacobs as well. "I know the rotisserie chicken did not die of natural causes . . . did not drift off to sleep in its (sic) old age surrounded by loved ones and grandchicks . . . But modern society has done an excellent job of shielding me from this fact." In other words, society has helped him (and millions of others) live a lie. But now Truth is breaking in. "The chicken kind of looks like Jasper . . ." (the author's sweet, spunky toddler son). The bird has "the same big eyes, the same cocked head . . . . I'm playing Abraham to the chicken's Isaac. And I don't have even a speck of Abraham's faith. I feel nauseated and loosen my grip. The chicken flies out of my hands . . ." Someone else recaptures the poor victim, and soon the slaughterer's gloves are washed in his blood. . . "I thank God that he discontinued the daily need for ritual slaughter. I had enough trouble with a chicken. I'd hate to try a goat or an ox (pp. 164-65)."

Eventually, Jacobs wisely goes vegetarian, though not immediately after this traumatic event, which is not listed explicitly as a cause for his decision (though it must have influenced it). The reasons he gives: it is much easier to keep Biblical dietary laws "if you steer clear of the animals. Plus, according to the Bible, the human race started out as vegetarian . . . . (page 307)."

After his year Jacobs was still an agnostic, though now he called himself "a reverent agnostic." Trying seriously not only to observe impractical and violent ritual laws but also to love his neighbors, to refrain from lying and flattery, and spending time in prayer of thanksgiving and intercession, did leave him with a sense of awe, an appreciation for the sabbath (which he still observes), greater caring for others, and strengthened integrity. We may hope he has continued his nonviolent diet as well.

--Benjamin Urrutia and Gracia Fay Ellwood

Recipes

Soupe aux Châtaignes (Provençal Chestnut Soup)

Serves 4

2 lbs. chestnuts

2 lbs. chestnuts

2 T. extra virgin olive oil

1 medium yellow onion, chopped coarsely

1 shallot, minced

1 clove garlic , minced

2 carrots, peeled and chopped

1 stalk celery, chopped

1 potato, peeled and chopped

½ tsp. sea salt, or to taste

freshly ground black pepper, to taste

3 cups warmed spring water

⅔ cup soy milk

Using a sharp paring knife, cut an “x” on each chestnut. Drop in boiling water for 10 minutes. Turn off the heat, but allow the chestnuts to remain warm in the water. Peel and chop coarsely. Set aside.

In a large saucepan sauté onion and shallot in olive oil over medium heat until translucent. Return chestnuts to saucepan, stir to coat with olive oil. Add garlic and sauté 1 minute longer; add carrots, celery, potato, salt and black pepper to taste. Add hot spring water; bring to light boil; cover and turn heat down to low; cook 30 minutes. Remove from heat; allow to cool briefly, in order to handle safely. Pour soup into a blender or the bowl of a food processor. This will need to be done in 2 or more batches. Process until smooth. Return to saucepan; add soy milk; reheat slowly. Serve with freshly made croutons

Croutons:

6 slices French bread, cut into 1 ½ inch chunks

3 T. extra virgin olive oil

2 cloves garlic, peeled and crushed

Place olive oil in a heavy skillet. When oil is hot, add garlic and cook for one minute to release flavor. Then add the chunks of bread and sauté until well coated with olive oil and are golden. Remove and store in a paper bag until ready to garnish soup.

If I had to choose my favorite soup, it would take me a matter of seconds to name this one. It is so creamy, sweet and absolutely delicious that I make it as soon as chestnuts become available, usually in November. It’s labor intensive, but worth every minute of the effort.

-- Angela Suarez

�Minestra di Riso e Castagne (Chestnut and Arborio Rice Soup)

Serves 6

2 lbs. chestnuts

1 small yellow onion, chopped

2 carrots, peeled and chopped

2 stalks celery, chopped

1 potato, peeled and coarsely diced

8 cups vegetable broth

2 bay leaves

1 cup arborio rice

sea salt, to taste

Using a sharp paring knife, cut an “x” on flat side of each chestnut. Place in a pot of boiling water and boil for 5 minutes. Turn off heat, but leave in water to maintain warmth of the chestnuts. Peel chestnuts while hot. Once all chestnuts are peeled, chop coarsely and set aside.

In a large soup pot, sauté onion until translucent. Add carrots, celery, potato and stir well. Add chestnuts, vegetable broth and bay leaves. Bring to a boil. Reduce heat, simmer, covered, for 1 ¾ hours. Add rice and boil gently for 17 minutes. Season to taste with sea salt. Discard bay leaves. Serve immediately.

The combination of chestnuts and rice is delightful when chestnuts are plentiful in the autumn and early winter months.

-- Angela Suarez

�

La Crique (Potato Pancakes)

Serves 2

2 T. extra virgin olive oil

2 T. extra virgin olive oil

2 cups coarsely grated potatoes

1 clove garlic, finely chopped

2 T. parsley, chopped

1 T. nutritional yeast + 2 T. soy milk, plain flavor, mixed well together

½ tsp. sea salt, or to taste

freshly ground black pepper, to taste

Extra virgin olive oil, for cooking

Warm 2 T. extra virgin olive oil in a heavy skillet; add grated potatoes, garlic, and parsley. Cover and cook for 2 or 3 minutes, stirring once or twice. Cool slightly.

Heat 1 T. extra virgin olive oil in an omelet pan.

Meanwhile add the potato mixture to the nutritional yeast and soy milk mixture; add salt and pepper and pour into hot oil. Cook over medium-high heat until set on the bottom. Place a dish or lid larger than the circumference of the pan over it; flip pan quickly to transfer pancake to dish or lid, then slide it back into skillet, cooked-side up. Cook other side for about 5 more minutes, until golden brown. Serve immediately.

La crique is a thick pancake, made with grated potatoes. It is delicious served with a mixed greens salad vegetables and crusty French bread.

-- Angela Suarez

�

Carob Energy Bars (for Canine Friends)

makes about 3 dozen, depending on sizes and shapes cut

2 cups organic whole wheat flour

¼ cup organic carob powder

¼ cup chopped seeds, such as sunflower or pepitas

1 T. nutritional yeast

1 tsp. baking powder

½ tsp. baking soda

1 ½ cup soymilk or spring water

¼ cup organic all natural smooth peanut butter

⅓ cup safflower oil

2 T. molasses

Preheat oven 350° F.

In a large mixing bowl combine whole wheat flour, carob powder, chopped seeds, nutritional yeast, baking powder, and baking soda.

In a glass 4-cup measuring cup, whisk together soymilk, peanut butter, safflower oil and molasses until well blended. Pour into the dry ingredients and stir to form a dough. Turn out onto a lightly floured work surface and knead until soft and workable. Using a rolling pin, roll out to about ½ inch thickness and cut into squares or shapes. Place on well oiled cookies sheets. Bake until completely done, but not browned, about 20 - 30 minutes. Cool on baking racks and store in airtight containers in the refrigerator or freezer.

Dogs who love to run, chase and catch toys use lots of energy. They need enough calories to keep them going. My companion dog is full vim and vigor and requires nutrition packed snacks along with her balanced diet to keep her at a good weight.

-- Angela Suarez

My Pilgrimage:

God's Lambs

Judy Carman and lamb friend at Farm Sanctuary

Judy Carman and lamb friend at Farm Sanctuary

It all began with the lambs, I suppose. Of course, I adored animals from birth, as I think all children do. (How else to explain the endless stream of children's books filled with stories and pictures of adorable animals.) But when I was 10 years old, every kid's dream came true for me. My family moved to the edge of town onto 7 acres with a pasture. A pasture! That meant we could share our lives with more animals.

When the lambs arrived to live with us and have their babies, I fell in love with them, of course. In my naïve imagination, we would always be together. I spent as much time as I could with them. They were so perfectly innocent, and they loved to be hugged and cuddled. Each one had his or her own special personality, and, of course, the babies—oh, the babies—to be holding them was to be holding a little piece of heaven.

I loved to look at the picture of Jesus holding a lamb in his arms, and it gave me a sense of the sacredness of these precious beings and their mystical connection to Divine Love.

Then one day, as you have already no doubt guessed, I came home from school to an empty pasture. No lambs. No warning. No chance to save them. Where had they been taken? Yet my tears at their loss were nothing in comparison to the next shock I was to experience.

It was dinnertime, and the table was filled with the usual meal over which my mother had faithfully labored. The big hunk of meat was, as usual, the centerpiece of the meal and, somehow, a symbol that we were prospering and well-fed. And then it happened. Someone—I don't recall who, but someone who knew, spoke glowingly of the delicious lamb we were eating.

There it was—for me—as for so many of us—the sudden, overwhelming realization that meat comes from the animals we love, animals we see in books, animals in pastures, animals whom we know personally; animals whose eyes once shone brightly with the joy of living. I might as well have discovered I was eating my dog or my sister. I was inconsolable. What kind of world was I living in where friends ate friends; where innocent, defenseless animals were taught to trust and then be taken away without goodbyes, brutally killed and devoured?

Such things are called the loss of innocence in children. It is also the loss of innocents, the terrible loss of billions of innocent beings. And historically, both losses have taken a terrible toll on the soul of humanity.

From that point on, I did not want to eat meat. (It took me many more years to learn about the suffering inherent in milk and eggs.) However, this was the '50's in Kansas. My father was a hunter. My uncles ran the stockyards and slaughterhouse. I had never heard of vegetarians; perhaps my parents hadn't either. I became known as “woolly minded” for not wanting to eat animals. I guess I was, since it was the woolly lambs themselves who transformed and renewed my mind. So I ate very little meat and fed a lot to the dogs under the table. The problem was that I substituted white bread, ice cream, and doughnuts for the meat, thus leading to the predicted conclusion that I had to eat meat to be healthy.

Yet my spirit nagged at me. It was truly a Divine blessing to love and be loved by animals considered by society to be only a commodity for human use. While it set me out on the fringe of society, it connected me to nature and the miracle of life, and I am forever grateful for that.

Finally, in my 20's I began hearing about vegetarianism and learning how to live in that way. As my journey, perhaps all of our journeys, has continued, the public has become more aware of the atrocities, and some reforms and some liberations have taken place. With the help of the information that came out from the many animal rights groups that formed, I began to learn that this was not just about avoiding the eating of animals. This was about changing the entire world view of humanity toward nature and all life.

This was not just a new way to eat; this was indeed a spiritual, intellectual, ethical, and moral revolution. Realizing this, I felt compelled not only to leave off eating animals, but also to speak out for them and for the new paradigm of living in harmony with all. Instead of assuming that human beings have the right to dominate, exploit, and use everything and everyone deemed unable to resist domination, we must learn to live in cooperation and mutual love with all creation.

This is indeed a spiritual journey for all humanity and all life. Gandhi explained to his followers that the reason they were to suffer and not resist abuse and torture at the hands of their persecutors was because such willingness to suffer would open the hearts of the persecutors and transform them into allies. As animal suffering continues to be exposed in the news, online, and in print, the opportunity for the hearts of human beings to open increases.

I came full circle a few months ago when I visited Farm Sanctuary in Watkins Glen, New York. There I was able to snuggle with lambs once again and bask in their sweet and peaceful presence. They were as I remembered them. Like dogs, they gathered among us asking for hugs and caresses. They looked at me so trustingly as my lamb friends had done so long ago. But the innocent trust of these lambs will not be betrayed.

May all lambs be safe from harm. May all beings be free. May all human beings awaken to Universal Love and ahimsa.

--Judy McCoy Carman

Judy Carman, a former therapist and program director for mental health clinics, is an activist for animal rights, environmental protection, justice, and peace. She is author of Born to Be Blessed: Seven Keys to Joyful Living and Peace to All Beings: Veggie Soup for the Chicken's Soul. She is co-founder of Animal Outreach of Kansas (www.animaloutreach-ks.org), and co-coordinator of the Worldwide Prayer Circle for the Animals. Judy invites you to join the prayer circle at www.circleofcompassion.org.

May we all hold the vision of a better world and from our hearts repeat each day: "May Peace Prevail on Earth" and "Compassion Encircles the Earth for All Beings Everywhere."

Judy was one of the first contributors to The Peaceable Table; see her letter and picture at PT 2 Aug-Sep '04. To see a review of Peace to All Beings, see PT 5 Dec. 2005; to order this book, visit www.lanternbooks.com

Letters

Dear Friends,

As per your article about "the close links between bullfighting and Roman Catholic piety" : Pope Pius V (1504-1572) who was later canonized, spoke up strongly against bullfighting. To quote a PETA web page, he "'decreed that bullfights are 'altogether foreign to piety and charity.' He wished that ' these cruel and disgraceful exhibitions of devils and not of men be abolished,' and he forbade attendance at them under penalty of excommunication."

The web page, entitled "Bullfighting: A Tradition of Tragedy," is located at www.peta.org/mc/factsheet_display.asp?ID=64 and cites as the source of the pope's quote "Bullarum Romanorum Pontificum Vol. 4, 2nd Part, 1567, 402-4."

--Virginia Haddad

The PETA website further points out that Barcelona (in the province of Catalonia) recently declared itself “an anti-bullfighting city,” and 38 Catalan municipalities followed its lead.(13) . . . Interest in bullfighting has also declined in Mexico and Portugal. The tradition still has a strong base elsewhere in Spain, however, and there are bullrings in five cities in France. The PETA web page gives the addresses of the US ambassadors of Spain, Mexico, and France, and urges readers to write them that they will not visit their countries because of this legalized cruelty.

Dear Friends,

. . . . There are really good things about the anti-bullfighting movement happening in Lima, now. Please keep me in your prayers so my eyes will recover and be back to normal soon.

It was nice to hear about my fellow activist, San Martin de Porres. One thing the article forgot to mention is that he is depicted with a pigeon/dove, a mouse, a cat and a dog. His house and the convent were located (and still are) in downtown Lima in an area where, at the time, there were a lot of abandoned, injured, and stray dogs. He used to take care of all of them, especially the ones who were inflicted with scabies and other skin diseases. With lots of compassion and patience, he would talk to the ignorant and cruel people who kicked and threw boiling water at them. It is indeed an honor to follow his steps. Next time I am in Lima I will visit his sanctuary again and take pictures for you guys.

--Maru Vigo

Thanks, Maru!

Dear Friends,

Check out the November 19 issue of Newsweek: on page 66, there is a full-page essay on Animal Rights! And on page 72, there is a brief article on vegetarianism for children. . . .

In South America, San Martin de Porres is called El Santo de los Ratones because he loves mice. Well, my faithful friend Kitty Nitro Qudsy also loves "mouses," but in a bad way, for the wrong reasons. Fortunately, there are no rodents in our apartment, so he's slain no one in years. The vegan foods he likes to eat include refried black beans, peanut butter, bread, and mesquite-flavored potato chips. He likes to steal them from my bowl better than to eat them from his own bowl . . . .

--Benjamin Urrutia

Benjamin is able to enjoy his friendship with Kitty Nitro Qudsy because he cured himself of a cat allergy years ago by repeatedly explaining to his immune system that it was misguided, that cat dander is harmless. He would be interested in corresponding with anyone else who tries this.

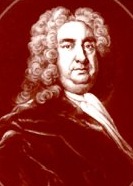

Pioneer: George Cheyne, 1671-1743

The birthplace and family of Scottish physician George Cheyne are not recorded in his books or letters, but apparently he was the same George Cheyne mentioned in records as the son of Marie and James Cheyne of Auchencreive, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, baptized in 1673. A studious youth, Cheyne received a good education at the University of Edinburgh. His parents had intended him for the clergy, but he chose medicine. Encouraged by his professor, Dr. Pitcairne, he wrote the first of a number of treatises on health, based on careful observation of patients, intermixed, not surprisingly, with a number of scientifically unsubstantiated ideas current at the time.

The birthplace and family of Scottish physician George Cheyne are not recorded in his books or letters, but apparently he was the same George Cheyne mentioned in records as the son of Marie and James Cheyne of Auchencreive, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, baptized in 1673. A studious youth, Cheyne received a good education at the University of Edinburgh. His parents had intended him for the clergy, but he chose medicine. Encouraged by his professor, Dr. Pitcairne, he wrote the first of a number of treatises on health, based on careful observation of patients, intermixed, not surprisingly, with a number of scientifically unsubstantiated ideas current at the time.

After taking his MD around 1700, he moved to London to begin practicing medicine. Interestingly, in order to build up a practice, one had to frequent taverns. Being cheerful, a lively and witty conversationalist, and fond of food and drink, he took to this life all too well; his girth expanded along with his popularity and his practice. After some years he became obese, with major health problems: shaking hands, severe headaches, giddiness, symptoms of apoplexy (coronary heart disease), and depression.

He had to take to his bed, whereupon he found that his good friends vanished from his life. Forced to think about what friendship and the purpose of life really were, he devoted his life to God, and set himself a course of religious reading from the Church Fathers onward. He also changed his rich diet to one focused on vegetables, fruit, and milk, with only a little meat. He lost a great deal of weight, regained his health, and was able to resume his medical practice and his writing, with particular emphasis on the causes and cures of depression. He pioneered a form of "talking cure" for the depressed, and had an empowering effect on his women patients.

However, as time passed, his habits of overindulgence crept back, and so did his weight, which eventually topped 32 stone (about 450 pounds); he could not get in and out of his carriage to make house calls without help. (Perhaps he needed a pusher behind him and a puller in front?) His bad health returned with it. He went back to a moderate, now strictly lacto-vegetarian, diet, and was again rewarded with weight loss as well as a return of health and energy. This time he maintained his discipline for the rest of his life, and preached what he practiced.

Resuming his medical practice and his writing, he stressed vegetarianism (which was not quite so popular with his readers as his earlier works). Overall, however, he was very influential, including as patients and/or friends several prominent people of his time, including the novelist Samuel Richardson, essayist and lexicographer Samuel Johnson, and reformer John Wesley, who became a vegetarian thanks to Cheyne's influence (see PT 17 Dec. 2005).

Although health issues originally triggered his interest in vegetarianism, compassion for animals became a part of his motivation, perhaps as a result of his spiritual awakening. In Essay on Regimen . . . , he writes

The question I design to treat of here is, whether animal or vegetable food was, in the original design of the Creator, intended for the food of animals, and particularly of the human race. And I am almost convinced it never was intended, but only permitted as a curse or punishment . . . . He was a bold man who made the first experiment. To see the convulsions, agonies, and tortures of a poor fellow-creature, whom they cannot restore nor recompense, dying to gratify luxury, and tickle callous and rank organs, must require a rocky heart. . . . . I cannot find any great difference , on the [basis] of natural reason and equity only, between feeding on human flesh and feeding on brute animal flesh, except custom and example.

The St. Francis and St. Martin de Porres kind of mystical pioneer can inspire us by expanding our view of what is possible, but for some they may seem too stratospheric in their rapturous and selfless spirituality. George Cheyne is a more down-to-earth model for 21st-century people who want to make the world a better place, but still struggle with the temptations of the world around them. Cheyne wanted both to save the world and to savor it; he taught himself before he taught others; he disciplined himself, slipped, renewed his discipline, and, in dependence on God, succeeded. He might have applied to himself a paraphrase of Paul's words in 2 Corinthians 4:16: "As the outer self diminishes, the inner self is renewed day by day ."

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

Based on The Heretic's Feast by Colin Spencer

and an online essay on George Cheyne by Bob Fyvie

Poetry:

Hodge, the Cat

Hodge, the Cat

Burly and big, his books among,

Good Samuel Johnson sat,

With frowning brows and wig askew,

His snuff-strewn waistcoat far from new;

So stern and menacing his air,

That neither Black Sam, nor the maid

To knock or interrupt him dare;

Yet close beside him, unafraid,

Sat Hodge, the cat.

"This participle," the Doctor wrote,

"The modern scholar cavils at,

But," - even as he penned the word,

A soft, protesting note was heard;

The Doctor fumbled with his pen,

The dawning thought took wings and flew,

The sound repeated, came again,

It was a firmer, stronger "Mew!"

From Hodge, the cat.

"Poor Pussy!" said the learned man,

"Poor Pussy!" said the learned man,

Giving the glossy fur a pat.

It is your dinner time, I know,

And--well, perhaps I ought to go

For if Sam every day were sent

Off from his work your fish to buy,

Why, men are men, he might resent,

And stint or kick you on the sly;

Eh! Hodge, my cat?"

The Dictionary was laid down,

The Doctor tied his vast cravat,

And down the buzzing street he strode,

Taking an often-trodden road,

And halted at a well-known stall:

"Fishmonger," spoke the Doctor gruff,

"Give me six oysters, that is all;

Hodge knows when he has had enough,

Hodge is my cat."

Then home; puss dined, and while in sleep

He chased a visionary rat.

His master sat him down again,

Rewrote his page, renibbed his pen;

Each "i" was dotted, each "t" was crossed,

He labored on for all to read,

Nor deemed that time was waste or lost

Spent in supplying that small need

Of Hodge, the cat.

The dear old Doctor! Fierce of mien,

Untidy, arbitrary, fat,

What gentle thoughts his name enfold!

So generous of his scanty gold,

So quick to love, so hot to scorn,

Kind to all sufferers under heaven,

A tend'rer despot ne'er was born;

His big heart held a corner, even

For Hodge, the cat.

--Susan Coolidge (Sarah Chauncy Woolsey), 1835-1905

Slightly edited

Sarah Chauncy Woolsey was primarily a writer for children; she also edited a collection of Jane Austen's letters. The tabby pictured above is Thomas Henry, cat friend of Jon Bickley, a sculptor who used him as a model for a statue of Hodge sitting atop the Dictionary. It may be seen in front of Samuel Johnson's house in London.

Credits:

The Peaceable Table is

intended to resume the witness of that excellent vehicle of the Friends

Vegetarian Society of North America, The Friendly

Vegetarian, which appeared quarterly between 1982 and

1995. Following its example, and sometimes borrowing from its

treasures, we publish articles for toe-in-the-water

vegetarians as well as long-term ones, poetry, letters, book

and film reviews, and recipes.

The journal is intended to be

interactive; contributions, including illustrations, are

invited for the next issue. Deadline for the January issue

will be December 29, 2007. Send to graciafay@mac.com

or 10 Krotona Hill, Ojai, CA 93023. We operate primarily

online in order to save trees and labor, but hard copy

is available for interested persons who are not online.

The latter are asked to donate $12 (USD) per year if their means allow. Other

donations to offset the cost of the domain name, server, and

advertising notices are welcome.

Website www.vegetarianfriends.net

Editor: Gracia Fay Ellwood

Book and Film Reviewers: Benjamin Urrutia & Robert Ellwood

Recipe Editor: Angela Suarez

NewsNotes Contributors: Marian Hussenbux & Lorena Mucke

Technical Architect: Richard Scott Lancelot Ellwood

variations, in flocks of bird slaves across Europe and south Asia, and in most cases, was temporarily contained by a mass killing. The virus has even moved back to wild waterfowl, become benign to some of them, and thus proceeded to migrate across the world. It is loose among birds in thirty countries of the Eastern Hemisphere. As of November 2007, over two hundred people, most of whom had direct contact with birds, have died from it: about 60% of those who were known to be infected. (Compare the 1918 'flu, which killed between 5% and 20% of those infected, adding up to between 50 and 100 million people worldwide.)

variations, in flocks of bird slaves across Europe and south Asia, and in most cases, was temporarily contained by a mass killing. The virus has even moved back to wild waterfowl, become benign to some of them, and thus proceeded to migrate across the world. It is loose among birds in thirty countries of the Eastern Hemisphere. As of November 2007, over two hundred people, most of whom had direct contact with birds, have died from it: about 60% of those who were known to be infected. (Compare the 1918 'flu, which killed between 5% and 20% of those infected, adding up to between 50 and 100 million people worldwide.)

A.J. Jacobs, an agnostic of secular Jewish background, a bestselling author and an editor for Esquire magazine, decided to take the Bible seriously: not just read it, but actually obey all the commands and injunctions in both Testaments for a year. His main motivations were to understand religion better; to use the experiment as a basis for writing another funny, far-out book; and to do some genuine spiritual seeking. He also intended to show that Jewish and Christian fundamentalists are not as literalistic as they claim (they all pick and choose) and that biblical literalism is unworkable. He succeeds admirably in these aims. The book has even been optioned for a movie.

A.J. Jacobs, an agnostic of secular Jewish background, a bestselling author and an editor for Esquire magazine, decided to take the Bible seriously: not just read it, but actually obey all the commands and injunctions in both Testaments for a year. His main motivations were to understand religion better; to use the experiment as a basis for writing another funny, far-out book; and to do some genuine spiritual seeking. He also intended to show that Jewish and Christian fundamentalists are not as literalistic as they claim (they all pick and choose) and that biblical literalism is unworkable. He succeeds admirably in these aims. The book has even been optioned for a movie.  2 lbs. chestnuts

2 lbs. chestnuts 2 T. extra virgin olive oil

2 T. extra virgin olive oil  The birthplace and family of Scottish physician George Cheyne are not recorded in his books or letters, but apparently he was the same George Cheyne mentioned in records as the son of Marie and James Cheyne of Auchencreive, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, baptized in 1673. A studious youth, Cheyne received a good education at the University of Edinburgh. His parents had intended him for the clergy, but he chose medicine. Encouraged by his professor, Dr. Pitcairne, he wrote the first of a number of treatises on health, based on careful observation of patients, intermixed, not surprisingly, with a number of scientifically unsubstantiated ideas current at the time.

The birthplace and family of Scottish physician George Cheyne are not recorded in his books or letters, but apparently he was the same George Cheyne mentioned in records as the son of Marie and James Cheyne of Auchencreive, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, baptized in 1673. A studious youth, Cheyne received a good education at the University of Edinburgh. His parents had intended him for the clergy, but he chose medicine. Encouraged by his professor, Dr. Pitcairne, he wrote the first of a number of treatises on health, based on careful observation of patients, intermixed, not surprisingly, with a number of scientifically unsubstantiated ideas current at the time.  Hodge, the Cat

Hodge, the Cat  "Poor Pussy!" said the learned man,

"Poor Pussy!" said the learned man,