Guest Editorial: A Glimpse of the Peaceable Kingdom

by Rina Deych

If I believed in destiny, I'd swear it was destined for me to cross paths--or rather join paths--with an iguana.

I always had a fascination with lizards, dinosaurs, and dragons, and, in fact, painted many on tee shirts, school bags, and guitar straps. As a teenager I had a recurring dream that, while walking up the block to my house, I found a little dragon. I dreamt I brought him home and named him "Puff." My little Puff, so real I could actually feel his scaly skin, was sweet and gentle. Another example: I'd been thinking about getting a lizard tattoo for many years. Finally, about 15 years ago, I had an iguana tattooed on my chest by the famous Spider Webb.

Then, in the late summer of 1999, my chiropractor, Dr. Scott Schwager, found a young iguana sauntering down a sidewalk in Brooklyn. Had he been abandoned by his "owner?" Had he escaped from a window? He didn't tell his story. As Dr. Schwager chased him, the lizard picked up speed.

After an exhaustive chase, with the help of some friends, the chiropractor--a compassionate person who realized the creature could not survive in this climate in an urban setting--managed to catch him and bring him into his office. When the doctor's wife saw the thirteen-inch lizard, she screamed "You're not bringing that THING in here!"

They both looked at each other and said "Rina."

I went over to pick him up and fell instantly in love with him. I named him Sobe, after the iced tea with the lizards on the bottle. Over the years I had taken in various homeless cats, dogs, and birds, but I knew iguanas had rather different needs from those of my furry and feathered friends. After a quick search on the internet regarding the essentials of iguana care, and a phone call to Manhattan reptile rescuer Robert Shapiro, I went out to buy the necessary materials: an enclosure, ultraviolet lights, humidifier, ceramic heaters.

I went over to pick him up and fell instantly in love with him. I named him Sobe, after the iced tea with the lizards on the bottle. Over the years I had taken in various homeless cats, dogs, and birds, but I knew iguanas had rather different needs from those of my furry and feathered friends. After a quick search on the internet regarding the essentials of iguana care, and a phone call to Manhattan reptile rescuer Robert Shapiro, I went out to buy the necessary materials: an enclosure, ultraviolet lights, humidifier, ceramic heaters.

When he started to really grow (he is now almost five feet long from his nose to the tip of his tail), I had my (then) boyfriend build an 8'x8'x4' wood-frame Plexiglas loft enclosure, with a photomural of greenery in the background, attached to a tree branch and cat "trees" for him to climb on.

Sobe has thrived. Thankfully, iguanas are vegan! Every morning, I make him a huge salad of collard, mustard, and dandelion greens, Swiss chard, bok choy, various squashes, beets, melon, apples, grapes, and pears. The diet must be balanced as follows: 40% green vegetables, 40% yellow, and 10% fruit. He also likes bread as an occasional treat. (Many humans I know could learn a thing or two from Sobe's fresh, nonviolent meals!) He stays in his "upstairs apartment" for several hours, basking in the heat of his lamps.

Then he is ready for his social life. He clambers down the tree branch and makes the rounds, visiting every animal resident in the house: dog, twelve cats, and two parrots! Sometimes he naps with one or another of the cats; occasionally Cato the parrot perches on Sobe's long tail, grooming him.

Impressive as Sobe's "international" friendliness was, the most remarkable thing was yet to come. One day in the summer of 2003 I found an emaciated white-and-ginger kitten outside my house in terrible condition, more dead than alive. He was suffering from pneumonia, severe infections in both eyes (one of them already opaque from ulceration), ear infections, hair loss and lesions due to innumerable flea bites. At once I drove him to my vet, who thought he was hopeless and recommended euthanizing him.

But I had a funny feeling about this cat. I just felt with some de-worming, de-fleaing, and antibiotics, he'd be okay. The feeling turned out to be right. I wanted to name him "Popeye" because of his huge opaque eye that looked like it was going to pop out. My son, furious with this suggestion, said "That's disgraceful! Give him a dignified name." So I named him Johann, after my favorite composer, J.S. Bach.

As Johann began to recover, I introduced him to everybody's friendly neighbor from "upstairs." The first scene was not promising: Sobe immediately puffed himself up, preparing to defend his territory. But the kitten, despite all he had gone through, had no fear. He tried to snuggle up to the formidable-looking beast! Faced with this "love your enemy" approach, and a little gentle coaxing and guidance from me, Sobe soon calmed down, and his bluster melted away. Within an hour he had accepted Johann's friendship. And what a friendship it has turned out to be! Supremely loyal, this David-and-Jonathan pair hang out together, nuzzle one another, and sleep cuddled together.

When the story of the remarkable friendship of Mzee the giant tortoise and Owen, the baby hippo orphaned by the tsunami of 2004 was broadcast, BBC photographer Peter Greste was quoted as saying that this hippo-tortoise friendship was the first scientists had seen of a mammal and reptile bonding. I contacted him and told him "That's because these scientists haven't been to my house." I sent some photos of the odd couple to Mr. Greste, and to Dr. Paula Kahumbu, the manager of Haller Park Animal Sanctuary in Kenya who took Owen in. Mr. Greste's gracious response was "Even BBC journalists occasionally get it wrong." He went on: "Thanks for forwarding your website. The photos are really extraordinary." Dr. Kahumbu indicated she was eager to share the photos with her colleagues.

I believe that with love anything is possible. A friend of mine has a theory that the reason the animals I live with get along so well is that they have "species confusion." Maybe if our own species had a little of that, we'd have

a more peaceful, sustainable planet.

In some persons, a certain dimension of the Inner Light/Love is developed to the point that they seem to have around them a powerful field that affects animals, awakening in them a sense of the inter-species peace of the hidden Paradise. This may be the case with the author of this essay.--Editor

Photo of Rina and Sobe by Julian Deych. Photos of Johann and Sobe by Rina Deych. The lead photo won PETA's 2005 contest for pictures of rescued animals.

Photo of Rina and Sobe by Julian Deych. Photos of Johann and Sobe by Rina Deych. The lead photo won PETA's 2005 contest for pictures of rescued animals.

Letter

I want to tell you how much I continue to enjoy The Peaceable Table. But I especially wanted to say how deeply moved I was by Pam Ahern's feature article in the April issue. It is a stunning story about the full scope and the many forms of compassion, and I thank her so much for writing it, and you for printing it!

All best & many blessings,

Juli Maltagliati

Juli was profiled in "My Pilgimage" PT July '07

News Notes

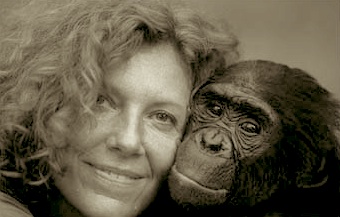

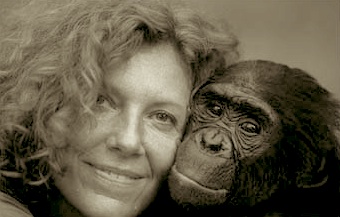

Sanctuary for the Bonobos

The April 21, 2008 issue of Time features an article, on pages 52-55, "Eden for the Peaceful Apes," by Alex Perry, with photos by Cyril Ruoso and Alexis Lewles. Located in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Sankuru Reserve - which provides refuge for bonobos, for ten other species of primates, for elephants, and for okapi-- is the result of the wise and valiant efforts of one Andre Tusumba. This great man has arranged matters so that the protection of the bonobos and the other jungle creatures serves to provide a hospital, a school, and roads for the local humans. This has won the enthusiastic cooperation of the surrounding people. The Sankuru Sanctuary spreads over 30,750 square kilometers (11, 803 square miles), about the size of Massachusetts. Bonobos, who may be our closest relatives, are similar to chimpanzees but more apt at finding peaceful ways to resolve tensions. The article concludes with these words: "There are plenty of reasons to save the Congo Basin, but teaching the highest species on the planet the value of a little peace and love is one more very good one." If we can learn to follow bonobos' peace-loving ways, perhaps we will become truly worthy of being called the "highest" species.

- Contributed by Benjamin Urrutia

Essay Review: "Minds of their Own"

The March 2008 National Geographic contains a milestone article on animal intelligence, written by Virginia Morell with photographs by Vincent J. Musi. It examines some important research that has been going on in the last several decades on the mental capacities of several species. It also quietly demolishes and dismisses some arguments used by the Dogmatic Deniers.

The March 2008 National Geographic contains a milestone article on animal intelligence, written by Virginia Morell with photographs by Vincent J. Musi. It examines some important research that has been going on in the last several decades on the mental capacities of several species. It also quietly demolishes and dismisses some arguments used by the Dogmatic Deniers.

Some important facts I learned from reading this article:

-Alex the African Grey Parrot not only learned many words and how to use them but also creatively invented new words.

-Betsy, a border collie, understands over 330 words; she will retrieve named objects, link photos with the objects they depict.

-Every time a new mental ability is found in non-human animals, the Dogmatic Deniers change the definition of intelligence. (In fact, I knew a man who, in order to deny intelligence to animals, developed a definition of intelligence so restrictive that it would have excluded most humans-- including me.)

-The ability to imitate the behavior of another, long used as a ploy to deny intelligence ("Oh, it's just monkey see, monkey do.") actually is itself a skill that requires high intelligence and a developed image of self. The imitator needs to form a mental image of the Other and then adjust his or her own self accordingly. Neither is as simple or easy as popularly imagined.

-Dolphins have a strong grasp of syntax, and a creative vein.

However, in my opinion the most powerful statement for non-human intelligence in the article is not any array of facts, but the close-up photograph of Kanzi the bonobo (above). Anyone who can look into Kanzi's brilliant and deeply penetrating eyes, and still deny he is an intelligent person, has an outrageous capacity for Denial.

I needed no convincing of the reality of animal intelligence. On the other hand, I suspect a Dogmatic Denier would not be convinced even if whole encyclopedias full of data were presented. But is comforting and encouraging that such a reputable and widely read publication as National Geographic is addressing the many people somewhere between, and doing so in an elegant and effective manner.

--Benjamin Urrutia

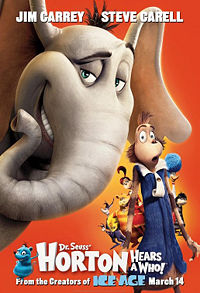

Film Review: Horton Hears a Who!

An animated film based on the classic book by Theodore "Dr. Seuss" Geisel. Jim Carrey as Horton, Steven Carrell as the Mayor of Whoville. Carol Burnett as the Sour Kangaroo. Jesse McCartney as Jojo Who.

Horton the elephant, our hero, discovers an entire microcosmic civilization existing in a clover. The narrow-minded society of jungle animals around him does not believe such a microcosm can exist; they persecute Horton and, in various hair-raising adventures, threaten to destroy the clover.

Horton the elephant, our hero, discovers an entire microcosmic civilization existing in a clover. The narrow-minded society of jungle animals around him does not believe such a microcosm can exist; they persecute Horton and, in various hair-raising adventures, threaten to destroy the clover.

His plight is reminiscent of the situation of animal defenders, whose open hearts and sympathetic imaginations let us share the intelligence and feelings in nonhuman animals, resulting in the conviction that they must be protected from mistreatment and slaughter. In both cases, defenders of the status quo reject the message and often attack the messenger. But the courageous Horton holds firm: "A person's a person, no matter how small." To this we may add: Or how big. No matter what color or shape. No matter how much hair or how many legs.

The movie has expanded Horton's adventures, and also added a parallel plot about how the Mayor of Whoville strives to convince his fellow Whos that the macrocosm exists, and what a danger it presents to them. I was moved to tears when Jojo Who - a very quiet (though very creative) young Who - finally invents a word, opens his mouth, and saves his world from destruction. Hey, if we find the right words and open our mouths we may just save not only many animal persons but our world from destruction.

All the characters in the book and film are talking animals, but the Whos, though subtly furry, are virtually human compared to the jungle animals in the macrocosm. Ironically, here it is the animal persons who are in power and are polarized over whether to save or destroy the humanoid persons.

Don't miss the movie; and by the way, if you have not read the book, please do not deprive yourself any longer of such a treat. If your heart is open and your sympathetic imagination is alive and well, I promise you you will enjoy it even if you are as big a grown-up as Horton.

- Review by Benjamin Urrutia

Recipes

Oven Baked Falafel

Serves 4

2 cups chickpeas, soaked and cooked tender

2 cups chickpeas, soaked and cooked tender

½ yellow onion, chopped

2 T. fresh Italian flat leaf parsley, chopped

1 tsp. sea salt (or to taste)

small pinch cayenne

½ tsp. chili powder

3 – 4 cloves garlic, chopped

1 tsp. ground coriander

1 tsp. ground cumin

1 tsp. baking powder

½ tsp. baking soda

¼ cup whole wheat flour

Preheat oven 375° F.

Place the drained, cooked chickpeas and the onion in the bowl of a food processor fitted with a steel blade. Add the parsley, salt, cayenne, chili powder, garlic, coriander and cumin. Process until blended but not entirely puréed. Sprinkle in the baking powder, soda and whole wheat flour. Use the pulse option on the processor to mix thoroughly. Dough should form a ball. Using a spoon to scoop, shape the chickpea mixture into thick patties, about 2 -3 inches in diameter

Place on well oiled baking sheets. Drizzle additional extra–virgin olive oil over the falafel patties. Bake 12 minutes; remove from oven, turn over and bake another 8 -10 minutes or until golden.

Delicious with a lemon tahini sauce (below) in pita bread. Also be sure to serve with fresh tomatoes, salad greens and sweet onion.

--- Angela Suarez

Lemon Tahini Sauce

Makes about ½ cup

½ cup tahini (ground sesame seed paste)

juice of 1 fresh lemon

2 tsp. extra virgin olive oil

1 T. spring water

½ tsp. sea salt

½ tsp. evaporated cane juice (or organic sugar)

freshly ground black pepper, to taste

Whisk all ingredients together in a small-medium bowl. Serve with Oven Baked Falafel (above).

-- Angela Suarez

Tsimmes

Part 1:

2 pounds sweet potatoes

2 large carrots, sliced

1 large tart apple, sliced

1 heaping cup chopped onion

20 large pitted prunes

juice of one large lemon

1 tsp. salt

½ tsp. cinnamon

2/3 cup orange juice

Part 2:

1 cup apple juice, or soy milk, or rice milk (formerly 2 eggs, but the substitutes work well)

¼ cup wheat germ, matzo meal or fine crumbs

½ tsp. salt

3 Tbl. margarine, cold, in thin slices

Grate half the sweet potatoes and set aside.

Cut the other half of the potatoes into bite-sized chunks. Combine this with all the other ingredients of Part 1 in a large deep casserole dish (spray first). Toss.

Mix grated potato with items in List 2. Pat onto top of first mixture. Dot with margarine slices.

Cover tightly and bake one hour at 350 F. Remove cover and bake another hour.

--Contributed by Virginia Holmes

Apple Spice Snaps for Canine Companions

Makes about 4 - 5 dozen cookies, depending on size of cookie cutters and thickness of dough.

4 cups organic whole wheat flour

½ cup organic cornmeal

2 T. safflower oil

2 tsp. cinnamon

1 cup grated fresh apple, or unsweetened applesauce

1 ½ cups spring water

Preheat oven to 350° F

In a large bowl, combine flour, cornmeal, safflower oil, and cinnamon. Using a wooden spoon, stir in water and grated apple. Stir well until a stiff dough forms. Turn out onto a lightly floured surface. Knead until dough is smooth. Roll out on a lightly floured surface to a ¼ inch thickness. Cut with cookie cutters. Bake until golden brown and crunchy. Baking time depends on thickness of the cookie. Check after 20 minutes; continue to bake as needed. Cool on racks and store in airtight containers.

A yummy treat for your canine friend.

--Angela Suarez

My Pilgrimage: An Idea of Equality

By Lee Hall

. . . . When I was growing up, my parents had a business in Mexico and I was once taken to a bullfight in which three bulls were killed. It affected me in a profound way. (Equally disturbing was the fact that the scene did not affect others similarly.) My parents tried to "snap me out of it" by telling me the meat of the dead bulls fed the poor. In retrospect, I don't know why I didn't stop eating meat there and then. I think there was some vague sense of having no choice. Generally, the Great They [my parents] said that humans had to eat meat or we'd die. Specifically, the issue of where the bull meat went seemed irrelevant; it failed to address my feelings about the bulls before they were meat. The suffering I witnessed could only be described as deliberate, slow torture.

. . . . When I was growing up, my parents had a business in Mexico and I was once taken to a bullfight in which three bulls were killed. It affected me in a profound way. (Equally disturbing was the fact that the scene did not affect others similarly.) My parents tried to "snap me out of it" by telling me the meat of the dead bulls fed the poor. In retrospect, I don't know why I didn't stop eating meat there and then. I think there was some vague sense of having no choice. Generally, the Great They [my parents] said that humans had to eat meat or we'd die. Specifically, the issue of where the bull meat went seemed irrelevant; it failed to address my feelings about the bulls before they were meat. The suffering I witnessed could only be described as deliberate, slow torture.

. . . . I spent time traveling with my parents, and other times away at school. When I was at home, I lived with two beautiful dogs, Rom and Monty. Rom was eventually stolen and Monty was killed by a kennel keeper in a botched attempt to force him to breed. Monty's death hurt me in the way any loss of a human friend or relative would.

. . . . When I began my university studies, I led a group that campaigned for the Equal Rights Amendment. The idea of equality dawned on me as something real and personal and essential. I began to understand that equality was not an academic theory; it was not sameness; it was not the relinquishment of individuality. It was not being "like" someone else or getting as much as others had. It was pure respect, and, as such, it couldn't be mathematically measured out and compared.

In 1983, I was living in England and attended a concert in Brixton, South London. Someone had placed leaflets on every fold-up chair. I read one of the leaflets carefully. It explained the effect of the holiday season on nonhuman animals. How many puppies were bought for children and later discarded, the number of furs sold, the number of geese and turkeys who ended up on platters, etc. I decided I should find the person who placed the flyers on the seats. Something about going to a concert with such a serious purpose was impressive.

That person was Robin and I met him and talked in the hall outside the concert arena. Robin had recently finished a prison term for a break-in at a chicken factory. He was not at the break-in, he told me, but he knew the people who were. As they had jobs and families, and he did not, he told the police he had done the break-in. In jail, the guards had taunted him for being a vegan. They had placed bets on when he would eat a ham sandwich, and they had given him no other food. This game had continued until he had suffered serious health consequences.

I could not imagine being as kind as this person was--it wasn't a matter of animals, it wasn't a matter of humans. Robin was completely kind in a way that bypassed categories and transcended measured amounts of what he could "afford."

I told him I would become a vegetarian. He invited me to see The Animals Film, a really stunning project in which Peter Singer makes an appearance. I believe at that time it had been shown once on the BBC and then banned. A newer documentary by Jennifer Abbot, called A Cow at My Table, uses some of its footage, but without the detailed indictment of several government agencies, pharmaceutical giants, and the enormous vested interest of both groups in biomedical research and in the livestock industry. I stopped eating animal products and was sick for three weeks, running to the toilet, it seemed, every few minutes. So, I ate fish and cheese for one more year, and in 1984 I successfully left animal products to the animals. I read Animal Liberation by Peter Singer and the nexus of racism, sexism, and speciesism became clear.

In late 1996, I entered law school and spent most of my time connecting everything I was taught, for better or worse, to the history of slavery. I see no boundary line between the enslavement of humans and enslavement of other animals. I see slavery as very much alive; the line separating owner from property has merely inched over a bit. Our legal literature admits to only a limited number of mistakes at once.

. . . . I am an associate at an immigration law firm and often notice similarities between the treatment of non-citizens and the treatment of nonhumans--more so than one might guess. . . .

From Voices From the Garden, edited by Sharon Towns and Daniel Towns. Used by permission of the editors. Attorney and abolitionist Lee Hall is the legal director of Friends of Animals; one of her recent works is Capers in the Churchyard: Animal Rights Advocacy in the Age of Terror. An extended interview with Ms. Hall may be found at

www.abolitionist-online.com/ _07hall.shtml.

Pioneer: Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso (43 B.C.E. - 17 C.E.), among the best-loved of Latin poets, lived most of his life during the long reign of the Emperor Caesar Augustus, the same ruler under whom Jesus was born. Like the Nazarene, he too suffered in the end from the harsh edge of imperial authority, though because of his class his punishment was not the hideous torture (and government terrorism) of the cross, but genteel exile. Unlike the impoverished Jew of a distant province, proclaimer of the Kingdom of God, Ovid was a clever, skeptical wordsmith at home in the stylish society of the great Roman capital, and his love was not the Reign of God but poetry. Yet, like certain other thinkers of his time, he may have been a vegetarian.

After two brief marriages that ended in divorce, Ovid's third union was relatively stable. But in his worldly circles, divorce, seduction, and infidelity seem to have have been taken for granted, and such a way of life was laid out for all to see in his exceedingly witty, and notorious, Ars Amatoria, (The Art of Love), of 1 C.E.

The much-talked-about writer then went on to pen other works of greater depth and variety of feeling, above all the famous Metamorphoses (8 C.E.), a retelling in elegant and amusing Latin verse of numerous classical myths. (This book, the best known source of such tales in medieval and renaissance Europe, greatly influenced Shakespeare and other later writers.) It is not likely Ovid believed very deeply in the Gods and heroes, with their various magical adventures and amours, of which he wrote so engrossingly; clearly his main passion was creating enchantments of mood and plot through his incomparable skill with words. But then, at the very end of this book, he got more serious.

First, though, we must note how disaster struck. The same year that Metamorphoses was finished, 8 C.E., the poet was summoned to a dressing-down from Caesar Augustus himself. After a hurried, perfunctory trial, presided over by the sovereign personally, Ovid was exiled from Rome to Tomi, a rough frontier outpost of Empire on the faraway banks of the Black Sea.

Although he was allowed to travel and live in reasonable comfort, and was even welcomed as a celebrity by the rustic Tomians, for someone like Ovid this was a grievous blow. A sophisticated urbanite if there ever was one, Ovid loved the vibrant city and the scintillating conversation of its cultivated classes; his wit, and willingness to read from his latest verse, always made him welcome at fashionable soirées. For him, exile from Rome was practically exile from life.

He sent verse back from his bleak refuge, to be published under the title Tristia (Sorrow). He wrote poignant letters describing his loneliness to his wife, who had stayed in the capital to manage their property in hope of his return some day. The deportee also penned elegant missives to the Emperor, pleading for reprieve. No answers were ever received, and Ovid never again saw Rome. (Many of these letters to wife and sovereign, and others to friends, have survived and are collected as Epistolae ex Ponto (Letters from the Black Sea).

What was Ovid's crime? Neither the exile himself nor any other source is explicit about this. What seems clear first, is that the debonair poet had fallen foul of a preoccupation of Caesar Augustus' later years, a campaign to reverse Rome's increasing moral laxity and decadence. The ruler was determined to restore the stern traditional values, celebrated by better-favored poets like Virgil, that had made the imperial race "great." In this new atmosphere, a book like Ars Amatoria would hardly have been well received in the highest quarters; indeed, Ovid's books were subsequently removed from public libraries. Yet one would think there must have been something more, something that offended the imperial family directly and personally, to call forth such sudden and draconian retribution – yet, puzzlingly, not until eight years after the book's issuance.

We can only speculate. However, it is a fact that Caesar's own grand-daughter, Julia, was involved in a sexual scandal that same year -- accused of having an affair with a senator -- and was herself being exiled to an Italian island, together with the infant born of the illicit union. What if the sovereign had found a copy of Ars Amatoria in her chamber, and with an outraged paterfamilias' wrath, had come down hard on the author and all his works?

However that may be, the last section of Metamorphoses exhibits moral concern of a very different kind from his earlier work. The poet evokes the noble Pythagoras (see PT 11, June 2005), whom he obviously greatly admired. After all the charming stories, the sage of Krotona is made to deliver a closing speech in favor of vegetarianism and harmlessness toward animals. The philosopher asks what harm the beasts had ever done to us to deserve slaughter, or why, with all the wonderful abundance of the fruits of the earth, we need meat besides. How, he inquires, could one who had fed a bird or beast with his own hands then turn and kill the trusting creature? Even worse, if possible, is the killing of richly bedecked animals at the altars, as though taking innocent life could somehow do the Gods service. After his appeal for compassion for animals, the poet has Pythagoras go on to describe another strong conviction of his, transmigration of souls, one reason why all conscious beings are kin.

Did Ovid really believe in these tenets, or were they mere fine language put in the mouth of another for literary effect? It is significant, perhaps, that it with with such strictures as these that he ends a book that is mostly fantasy. They somehow strike a different note, as though to say, "You don't have to regard all of religion very deeply, and certainly some of it, like animal sacrifice, is pretty bad. But now let the revered Pythagoras of old tell you what does matter: reverence for your fellow creatures, whose souls like your own circle through life and death." To this day no one knows Ovid's own heart in this matter. But the final section of Metamorphoses, Book XV, is worth pondering by anyone who is serious about the philosophical issues of diet, compassion, life, and death.

--Robert Ellwood

Krotona, Ojai, California

Poetry: Publius Ovidius Naso

Unlike the later Proclus, who was committed to vegetarianism but accepted animal sacrifices as something the Gods willed, Ovid's narrator voices a powerful critique not only of all killing of animals for food, but especially of sacrificing the innocent beasts whose very labor had produced the ceremonial grains.

Parcite, mortales, dapibus temerare nefandis

corpora! Sunt fruges, sunt deducentia ramos

pondere poma suo tumidaeque in vitibus uvae,

sunt herbae dulces, sunt quae mitescere flamma

mollirique queant; nec vobis lacteus umor

eripitur, nec mella thyme redolentia flore:

prodiga divitias alimentaque mitia tellus

suggerit atque epulas sine caede et sanguine praebet. . . .

Victima labe carens et praestantissima forma

(nam placuisse nocet) vittis insignis et auro

sistitur ante aras auditque ignara precantem

imponique suae videt inter cornua fronti

quas coluit, fruges percussaque sanguine cultros

inficit in liquida praevisos forsitan unda.

Protinus ereptas viventi pectore fibras

inspiciunt mentesque deum scrutantur in illis:

unde (fames homini vetitorum tanta ciborum!)

audetis vesci, genus o mortale? Quod, oro,

ne facite, et monitis animos advertite nostris!

Cumque boum dabitis caesorum membra palato,

mandere vos vestros scite et sentite colonos.

Mortals, refrain from defiling your bodies with sinful

feasting, for you have the fruits of the earth and of arbors,

whose branches bow with their burden; for you the grapes ripen;

for you the delicious greens are made tender by cooking;

milk is permitted you too, and thyme-scented honey:

Earth is abundantly wealthy and freely provides you

Her gentle sustenance, offered without any bloodshed . . . .

Since that which makes him so pleasing is what will most harm him,

a victim distinguished in figure and quite without blemish,

his horns gilded, trailing bright ribbons, is led to the altar,

where he, without comprehending them, listens to prayers,

and observes the barley he helped to cultivate sprinkled

between his horns: perhaps even sees in the basin,

held under his head by the priest, the knife blade reflected

a moment before his blood is spilled into the water. . .

So great is the human hunger to eat what's forbidden,

you mortals will dare even to feed upon this! Don't you do it,

I beg you! Pay close attention to my admonition,

and when you devour this flesh of your fresh-butchered cattle,

taste it and know you are eating your labor's companion!

Credits:

The Peaceable Table is

intended to resume the witness of that excellent vehicle of the Friends

Vegetarian Society of North America, The Friendly

Vegetarian, which appeared quarterly between 1982 and

1995. Following its example, and sometimes borrowing from its

treasures, we publish articles for toe-in-the-water

vegetarians as well as long-term ones, poetry, letters, book

and film reviews, and recipes.

The journal is intended to be

interactive; contributions, including illustrations, are

invited for the next issue. Deadline for the June issue

will be May 29, 2008. Send to graciafay@mac.com

or 10 Krotona Hill, Ojai, CA 93023. We operate primarily

online in order to save trees and labor, but hard copy

is available for interested persons who are not online.

The latter are asked to donate $12 (USD) per year if their means allow. Other

donations to offset the cost of the domain name, server, and

advertising notices are welcome.

Website www.vegetarianfriends.net

Photo of Kanzi by Vincent J. Musi

Editor: Gracia Fay Ellwood

Book and Film Reviewers: Benjamin Urrutia & Robert Ellwood

Recipe Editor: Angela Suarez

NewsNotes Contributors: Marian Hussenbux & Lorena Mucke

Technical Architect: Richard Scott Lancelot Ellwood

I went over to pick him up and fell instantly in love with him. I named him Sobe, after the iced tea with the lizards on the bottle. Over the years I had taken in various homeless cats, dogs, and birds, but I knew iguanas had rather different needs from those of my furry and feathered friends. After a quick search on the internet regarding the essentials of iguana care, and a phone call to Manhattan reptile rescuer Robert Shapiro, I went out to buy the necessary materials: an enclosure, ultraviolet lights, humidifier, ceramic heaters.

I went over to pick him up and fell instantly in love with him. I named him Sobe, after the iced tea with the lizards on the bottle. Over the years I had taken in various homeless cats, dogs, and birds, but I knew iguanas had rather different needs from those of my furry and feathered friends. After a quick search on the internet regarding the essentials of iguana care, and a phone call to Manhattan reptile rescuer Robert Shapiro, I went out to buy the necessary materials: an enclosure, ultraviolet lights, humidifier, ceramic heaters.  Photo of Rina and Sobe by Julian Deych. Photos of Johann and Sobe by Rina Deych. The lead photo won PETA's 2005 contest for pictures of rescued animals.

Photo of Rina and Sobe by Julian Deych. Photos of Johann and Sobe by Rina Deych. The lead photo won PETA's 2005 contest for pictures of rescued animals.

The March 2008 National Geographic contains a milestone article on animal intelligence, written by Virginia Morell with photographs by Vincent J. Musi. It examines some important research that has been going on in the last several decades on the mental capacities of several species. It also quietly demolishes and dismisses some arguments used by the Dogmatic Deniers.

The March 2008 National Geographic contains a milestone article on animal intelligence, written by Virginia Morell with photographs by Vincent J. Musi. It examines some important research that has been going on in the last several decades on the mental capacities of several species. It also quietly demolishes and dismisses some arguments used by the Dogmatic Deniers. Horton the elephant, our hero, discovers an entire microcosmic civilization existing in a clover. The narrow-minded society of jungle animals around him does not believe such a microcosm can exist; they persecute Horton and, in various hair-raising adventures, threaten to destroy the clover.

Horton the elephant, our hero, discovers an entire microcosmic civilization existing in a clover. The narrow-minded society of jungle animals around him does not believe such a microcosm can exist; they persecute Horton and, in various hair-raising adventures, threaten to destroy the clover. 2 cups chickpeas, soaked and cooked tender

2 cups chickpeas, soaked and cooked tender . . . . When I was growing up, my parents had a business in Mexico and I was once taken to a bullfight in which three bulls were killed. It affected me in a profound way. (Equally disturbing was the fact that the scene did not affect others similarly.) My parents tried to "snap me out of it" by telling me the meat of the dead bulls fed the poor. In retrospect, I don't know why I didn't stop eating meat there and then. I think there was some vague sense of having no choice. Generally, the Great They [my parents] said that humans had to eat meat or we'd die. Specifically, the issue of where the bull meat went seemed irrelevant; it failed to address my feelings about the bulls before they were meat. The suffering I witnessed could only be described as deliberate, slow torture.

. . . . When I was growing up, my parents had a business in Mexico and I was once taken to a bullfight in which three bulls were killed. It affected me in a profound way. (Equally disturbing was the fact that the scene did not affect others similarly.) My parents tried to "snap me out of it" by telling me the meat of the dead bulls fed the poor. In retrospect, I don't know why I didn't stop eating meat there and then. I think there was some vague sense of having no choice. Generally, the Great They [my parents] said that humans had to eat meat or we'd die. Specifically, the issue of where the bull meat went seemed irrelevant; it failed to address my feelings about the bulls before they were meat. The suffering I witnessed could only be described as deliberate, slow torture.