Editorial: "Don't Tell Me What to Do!"

Most of us who have urged--or mildly encouraged--others to stop eating animals, and given reasons, have at some time met with resistance of the "Don't tell me what to do" sort. It may range from a world-weary "You can't legislate morality" or "No Food Police, please," to a brusque "Mind your own business!" In all such cases, the protester is appealing to Freedom, which the lapel-grabbing, brother-are-you-saved vegevangelist is infringing.

Shades of the Prison House

And it's all very ironic, because the incensed defender of Liberty has little idea how much s/he is in fact manipulated in her menu choices. To begin with--in early childhood--did a parent explain the relevant facts to her, and then give her a choice in the matter? Imagine a dinner table scene: "This brown chunk on your plate comes from the body of a cow. Here's how it got here: the cow was standing in a meadow with her family and friends eating grass (or standing deep in poop eating grain mixed with drugs and dead cats and dogs), then she was pushed into a truck crowded with other scared cows, . . ." (et cetera, ad nauseam). "The pieces of her body have been heated up, which kills the dangerous germs, and spiced and salted, so they taste quite good now. Of course, if you don't want any, that's fine too; you can have a peanut butter sandwich. In fact, then you're more likely not to get a heart attack when you grow up, as Grandma did, or a painful kidney stone as Uncle Jerry did . . ."

The actual scenario in nearly all cases is only too well known. The parent spoons pureed flesh into the infant's mouth; when the child is old enough to ask where it comes from, she will hear a highly sanitized and conscience-numbing answer. If she still shows any disturbing vegetarian inclinations, the parent will probably pressure her to give them up via one or more of what Melanie Joy calls "the Three Ns": eating meat is Normal, Natural, and Necessary. Growing up, the child will find the Three Ns reinforced from every side.

The actual scenario in nearly all cases is only too well known. The parent spoons pureed flesh into the infant's mouth; when the child is old enough to ask where it comes from, she will hear a highly sanitized and conscience-numbing answer. If she still shows any disturbing vegetarian inclinations, the parent will probably pressure her to give them up via one or more of what Melanie Joy calls "the Three Ns": eating meat is Normal, Natural, and Necessary. Growing up, the child will find the Three Ns reinforced from every side.

Invisible Fetters: "It is a Ponderous Chain! "

Normal, says Joy, means that society carves out a road for us, a path of least resistance, rewarding us when we follow it and punishing us when we resist. Take restaurant fare. When vegans sit down in an all-vegan restaurant and look at a menu in which we can choose anything, that happy sense of breadth and liberation makes us sharply aware of the way in which most restaurant menus push us out onto a narrow margin. When we are to be guests at private dinners, often we must choose between betraying our principles or making our hosts and fellow-guests uncomfortable (if not hostile). A perusal of a newspaper's food section, or a walk through the average supermarket, assaults us with a stream of hurtful language and images. Critics with a turn for amateur psychol0gy pathologize us, or sometimes--more recently--regard our lifestyle as admirable but superhumanly ascetic. By contrast, those who are obedient to the norms can float through these areas of life on autopilot, and most do.

Natural means that the way things are, and have been for centuries, is the way they ought to be; they accord with the laws of Nature or the laws of God, or both. But it turns out that the people who set forth these laws are nearly always those at the top of the hierarchy, and, by remarkable coincidence, benefit from them. This is typical of cultural forms of oppression. Likewise, nearly all literary texts for centuries declared that women were by nature weak and fickle and inferior to men, designed by Nature and God to submit to the Stronger Sex. What unanimity! But "these", as a Jane Austen character astutely remarks, "were all written by men."

It is a small step from Natural to Necessary; thus, to defy natural and divine laws by abstaining from meat is tantamount to suicide. Without it, human beings--especially males--will be weak, unhealthy. "Where do you get your protein?" Ill health is not the only calamity many expect. Just as in past centuries slavery defenders claimed that the economy would collapse without the "peculiar institution," today one sometimes hears gloomy predictions that the economy would fall apart without the animal-food system. Another dire prediction is that the world would be overrun with "farm" animals, which are, after all, here to be eaten.

Comfortable Bedfellows

Cracks are opening in the Necessary category of this ideology regarding meat--it is still concrete-hard regarding dairy--but it is kept going both by the unthinking habits of consumers, and by the active control of powerful and enormously rich multinational firms and their bedfellows in the U.S. government. Few consumers know how tight and pervasive this control is. For example, unless a congressional or presidential candidate is very rich, s/he will need the campaign dollars of mega-corporations to win. Especially in farm states, this means agribusiness firms, related food corporations, and chemical companies like Monsanto. After s/he wins, their lobbyists will exert heavy pressure on her. And if she is so conscientious as to vote for laws that favor human health and animal welfare over corporate interests, she will find re-election steep uphill work.

Another way in which agribusiness controls consumers is via the revolving door onto influential food/farm committees: food corporation executives, certain research scientists, and government representatives regularly trade places. For example, government committees whose purpose theoretically is to promote the public's good health via dietary guidelines are usually staffed by those with financial links to the dairy, egg, and meat industries. Thus the soundness of their recommendations just might be questionable.

On the state level, pressure from agribusiness has led to passing of the notorious "food libel" laws, which make activists and scientists vulnerable to massive lawsuits if they publicize dramatic claims, however well researched, that major commercial food products are unhealthy. Under one of these laws a rich Texas cattleman brought a twenty-million-dollar lawsuit against Oprah Winfrey and Howard Lyman. Had Oprah not been a multimillionaire herself, I doubt that she and Lyman could have contested this suit successfully. The laws especially stifle the freedom of speech of persons who are not rich, and the freedom of the public to learn from them

Effective "Education"

Animal corporations also wield their influence apart from government. In Diet for a New America John Robbins shows that by giving out advertisements called "educational materials" to schools, the dairy, meat and egg boards brainwash virtually all citizens, from kindergarten on, into believing that their animal products are foundational to good health. Another example: the American Dietetic Association gives representatives of the dairy industry a major say in the formation of its dietary guidelines, which may have something to do with its recommendation to drink three glasses of cow milk per day. (Most persons of color are dairy-intolerant, but too bad.)

Animal corporations also wield their influence apart from government. In Diet for a New America John Robbins shows that by giving out advertisements called "educational materials" to schools, the dairy, meat and egg boards brainwash virtually all citizens, from kindergarten on, into believing that their animal products are foundational to good health. Another example: the American Dietetic Association gives representatives of the dairy industry a major say in the formation of its dietary guidelines, which may have something to do with its recommendation to drink three glasses of cow milk per day. (Most persons of color are dairy-intolerant, but too bad.)

Animal industry also wields influence over consumers via the media. The public has long been eager for news of scientific research into food and health, especially if it is "good news about our bad habits," as John McDougall is wont to say. But many people have become cynical about these media reports, because they so often contradict one another. One reason for this situation, as Colin Campbell points out in The China Study, is that research funded by agribusiness and other food corporations is likely to be presented to the public in seriously misleading ways with details regarding particular nutrients taken out of context. Another reason, says Campbell, is that authors of industry-friendly reports can muddy the media waters to create artificial controversy if independent research unfavorable to agribusiness gets published. Thus issues about unhealthy food are seldom settled in the public mind, and the dollars can keep rolling into the corporate till.

"Low-Priced Specials!"

Still another way in which agribusiness bamboozles the public is in the (apparently) very low prices of animal products. According to the Consumer Price Index rates, during the last fifty years while inflation has climbed dizzily--the cost of a new car has risen 1400% and typical housing nearly 1500%--meat prices have risen very much less, and the prices of eggs and chicken flesh, in particular, have not even doubled! It looks like a great boon for the consumer.

But the boon is an illusion; animal product prices are high too, but have only become invisible. The low figures on the price tag are made possible by increased efficiencies that must be called demonic, especially manipulative breeding practices that hasten growth, factory-farm crowding and automation, and high-speed slaughterhell procedures. The real costs are spread out widely. The animals, as we know, pay most dearly of all in miserable, painful lives and premature, agonizing deaths. Small farmers pay; they are either driven out of business or reduced to "sharecroppers" under the control of the megacorporations, taking the risks and losses without sharing in the bonanza. Slaughterhell workers, especially on the killing floor, pay through low wages, denied benefits, denied unionization, high injury rates, and psychological trauma caused by the violence they perpetrate. Stress leads some to vent by sadistic abuse of the animals.

Consumers also pay, more invisibly: in infections from contaminated products, in high rates of degenerative diseases fostered by eating so many cheap animal products, in high health insurance rates, in the danger of pandemics created by antibiotic-resistant germs. Consumers also pay in higher taxes. The visible price of cow flesh, in particular, would be many times higher if US cattlemen did not receive "welfare" in the form of cheap water rights and cheap grazing rights on public lands. The planet pays in hastened global warming, water pollution, rangeland degeneration, and rainforest devastation. Wild life pays in massacres by ranchers and the USDA's Wildlife Services, daily extinctions, and stripping of the oceans. Far from being as low as it looks, the price tag on factory-farmed animal products is astronomical.

The Courage to Become Free

The Courage to Become Free

Freedom of choice is largely illusory unless it is informed choice. But to become informed, one must turn off the autopilot and say goodbye to some familiar comforts. It means (to mix the metaphors) leaving the wide road of least resistance, and camping out on the narrow margins of our culture. There the invisible can be seen; the views are breathtaking, but not in the usual sense of the word; they are painful and frightening. (Camping on the margins does provide spiritual benefits--when deadened areas of one's heart come back to life, they bring new joys--but that blessing is usually discovered only later.) In effect, "Don't tell me what to do" most often translates into "I don't want to know all that uncomfortable stuff. It's easier to go on letting the system make my choices for me."

Only if we gather courage to open our hearts and minds to the truth can the truth set us free.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

Sources: Meat Market by Erik Marcus, Diet for a New America by John Robbins, Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows by Melanie Joy, The China Study by T. Colin Campbell

Unset Gems

"Forgiveness liberates the soul. That is why it is such a powerful weapon."--Nelson Mandela in the film Invictus

"Now at last I can look at you in peace. I don't eat you anymore."

--Franz Kafka, speaking to fish in a Berlin aquarium, overheard by his friend Max Brod

News Notes

Academic Action Against Obesity

It is well known that obesity has reached epidemic proportions in the US. Lincoln University in Pennsylvania is taking pioneering action to help students deal with this health challenge. In order to graduate, students must have a relatively healthy weight. According to a requirement instituted in 2006, university students with a body mass index (BMI) over 30 will have to take a physical education class as part of the "Fitness for Life" program in order to receive their diploma. Arguably, private universities have the right to set such requirements, but Lincoln does receive some public funding. To read the full article please see Fitness .

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

Food Linked to Mental Health

The Whitehall II study in the UK, which involved 3,486 participants, shed light on the link between our mental health and the food we eat. Scientists compared the incidence of depression among individuals consuming a diet high in fruits, vegetables and fish to that of individuals whose diet contained a high proportion of high-fat dairy food, processed meat, fried food, refined grains, and sugar-laden desserts. The results showed that a whole food diet was consistent with a 26 per cent lower risk for depression while a high processed diet was associated with a 58 percent chance of depression. To read the full article see Depression/Diet .

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

Cetacean Persons

An article summarizing recent scientific reports on dolphins gives examples of their intelligence, including the capacity to recognize themselves in mirrors (joining humans, apes, and elephants) and to share newly acquired skills and techniques with one another. Some claim they should be treated as non-human persons.

See Dolphins Leaping

--Contributed by Richard S. L. Ellwood

Letters

Dear Peaceable Friends,

My thanks to Sr. Faith Bowman for her "Beatitudes for a New Era." In this poem she has reached a new high level of prophetic inspiration . . . I dare say that Yeshua/Jesus himself would be glad to have these Beatitudes next to his own.

--Benjamin Urrutia

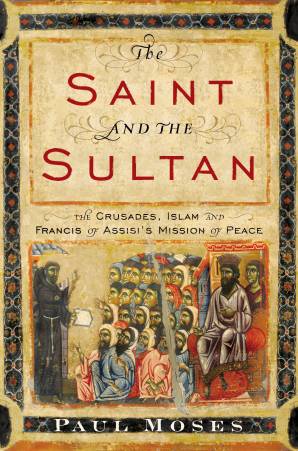

Book Review: The Saint and the Sultan

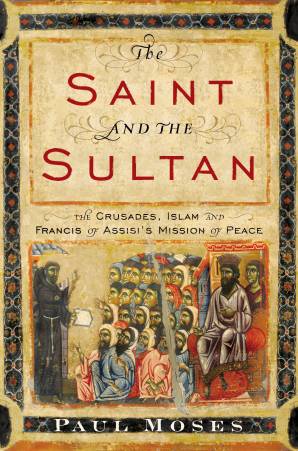

Paul Moses, The Saint and the Sultan: The Crusades, Islam, and Francis of Assisi's Mission of Peace. New York: Doubleday, 2009. 302 pages. $26.00 hardcover.

Francis of Assisi, usually portrayed in garden statuary as an obliging  human bird roost, is frequently sentimentalized into a medieval hippie who wandered about shoeless, preaching to avians and wolves. Certainly he was a lover of animals, and a strong advocate of peace between humans and the rest of God's creation. But he no less favored peace between human factions in a violent age; even more significantly, he saw the connection between peace on both these fronts. He knew that the war of humans against animals, and wars between humans, ultimately stem from the same source; we will not have peace in one without peace in the other.

human bird roost, is frequently sentimentalized into a medieval hippie who wandered about shoeless, preaching to avians and wolves. Certainly he was a lover of animals, and a strong advocate of peace between humans and the rest of God's creation. But he no less favored peace between human factions in a violent age; even more significantly, he saw the connection between peace on both these fronts. He knew that the war of humans against animals, and wars between humans, ultimately stem from the same source; we will not have peace in one without peace in the other.

In the year 1219, at the height of the crusader wars of Christian Europe against the Islamic world, Sultan Malik al-Kamil of Egypt received an unexpected visitor. At that moment the Fifth Crusade, attempting to retake Jerusalem overland by way of Egypt, was besieging the key Nile Delta city of Damietta. This crusade was more directly under the pope's control than the earlier efforts, as Europe's secular rulers had gradually lost interest in the frustrating venture. The commander of the armies in Egypt was, in fact, was none other than the papal legate, Cardinal Pelagius Galvani, whose status as a presumptive apostle of Jesus did nothing to mitigate his crusade's savagery. He reduced the tragic city by starvation and disease to little more than a graveyard, and rejected even the most generous offers of peace from the other side.

But on his ships sailing for the East had traveled another "legate"--who, though not even a priest, has very widely been considered among the most Christlike of all Christians. Francis, who had long believed he had a call from God to speak in peace with leaders of an Islam that most Europeans believed understood only the language of war, finally after much importunity won the Cardinal's grudging permission to cross the lines. The prelate seems to have believed he was sending the little Assisian to his death. Accompanied by one brother, carrying no weapons or even letters of introduction, Francis made his way to the sultan's splendid tent at his forward location just below the lines.

Malik al-Kamil was actually a man of more wisdom than nearly all captains on either side of the struggle. (Another exception was the remarkable Emperor Frederick II, with whom he later became good friends; they discussed mathematics and philosophy together while the two, theoretically enemies, enjoyed a prolonged truce.) The Muslim ruler was more familiar with Christians than most Christians were with Muslims, having a sizable minority of Egypt's Coptic Christians under his rule. He had known and respected Coptic monks; the Qur'an itself spoke favorably of those Christians who followed the priestly or monastic life sincerely (Qur'an 5:85). The scruffy, barefoot little man who now appeared before him, he assumed, was probably in the same category, or was like the Sufi mystics he also favored.

The friar and the sultan talked congenially at some length. While there is no exact record of all their conversation, certainly Francis endeavored the convert the other to Christianity, saying according to the most reliable chronicle, "We are ambassadors of the Lord Jesus Christ," and "If you wish to believe us, we will hand over your soul to God." But this was free and open dialogue. By his approach the saint was rejecting the Crusader's way of representing the Lord Jesus sword in hand. He asked only to be heard, convinced that if the ruler could be converted, any need for violence would vanish.

The sultan, who among other things had founded religious schools, was a staunch Sunni Muslim. He was not convinced, but neither does he seem to have been offended by the poor man's presentation of the Christian gospel. Indeed, he persuaded the unusual visitors to stay with him for several days, and offered them costly gifts on their departure. These Francis refused, but was willing to take a meal with his host. Author Moses comments of this: "It is a strange request coming from Francis, who had no problem with going hungry. But Francis must have had something else in mind besides slaking his hunger before the trip back to the Crusader camp. He always tried to imitate Jesus, who sought to realize the kingdom of heaven on earth through table fellowship -- by dining with people society despised." (p. 146) So he did dine in the house of Islam, and the monarch fed him and his companion abundantly.

Francis returned to Europe discouraged by the continuing warfare, above all by his Christian brethren's barbarism and their inability to see the Islamic foe except as demons who could be dealt with only through bloodshed. He himself retained a deep respect for Malik al-Kamil, and was even influenced by Muslim prayer and Sufi mysticism in his own spiritual life thereafter. But, as Paul Moses makes clear, even Franciscan writers sought very much to downplay this episode in the saint's life out of deference to the pope and his crusade. Most later biographies of Francis alter the peace mission grotesquely so as to make the Sultan a monster, sometimes reducing him to an infidel who spared his guest's life out of spite in order to deprive him of a martyr's crown.

Author Paul Moses, a former Newsday city editor, comments, "Spectacular as it was, Francis's journey to Damietta plays little role in the timeworn portrayal of the saint as a pious, miracle-working mystic and quaintly impoverished friend to animals and nature. As a journalist for some three decades, I'll just say, in the language of the newsroom, that the truth about Francis and his relationship to Islam and the Crusades was covered up. The key early biographies of Francis were written under the influence of powerful medieval popes -- the same men who organized the Crusades and used the battering ram of excommunication. . ." (p. 3) Author Moses seeks to extract the real story from alternative sources, including Muslim texts and Francis' own writings. In this, although not a specialist himself, he seems to have the best recent scholarship on his side.

Moses is well aware this is a timely moment for a reconstruction of Francis' relation with Islam. The more things change, the more they stay the same; there are those today in the Christian West who look at the Muslim world far more in the Crusader than the Franciscan way. But in the end the Crusades were futile, and indeed sowed centuries of enmity that has yet to die down. Moses discusses these issues insightfully, and ends with an account of small but significant groups -- one called Assisi Pax --which today are endeavoring the bring Christians and Muslims together in the spirit of reconciliation rather than confrontation, supported by mutual prayer and dialogue, explicitly in the spirit of the great saint and his meeting with the sultan.

Again, the little poor man's courageous search for human peace through love rather than the sword was intimately related to his view of animals. Moses writes:

Much as Francis's life of poverty flowed from his thirst for peace, so too did his celebrated compassion for animals. The early Franciscan accounts chronicled how he extended his compassion to hooked fish, caged rabbits, lambs bound for the slaughter, worms on the path, and birds. Francis taught the principles of nonviolence through his astonishing compassion for every creature. "The wild beasts harmed by others used to flee to him," Thomas of Celano wrote, ". . . What love do you think he bore toward the salvation of human beings, since he was so compassionate towards even the lower creatures?" (p. 38)

Little more need be said. This very timely, fascinating, and well-written book deserves a very wide readership.

--Robert Ellwood

Film Review: The Princess and the Frog

The Princess and the Frog. Walt Disney, 2009. Based on The Frog Princess by E. D. Baker. Written and directed by John Musker and Ron Clements. Starring Anika Noni Rose as Tiana, Bruno Campos as Naveen, Keith David as Facilier, and Oprah Winfrey as Eudora. Rated G.

This animated dramatization of the fairy tale takes a number of liberties with the Grimms' narative, bringing home its message of illusion and true worth in new and refreshing ways. This princess (Tiana) is not a spoiled brat but an obscure figure doing a lowly job, saving to realize a dream. The prince (Naveen) is the one who is spoiled and has to learn a lesson. Each can help the other grow.

This animated dramatization of the fairy tale takes a number of liberties with the Grimms' narative, bringing home its message of illusion and true worth in new and refreshing ways. This princess (Tiana) is not a spoiled brat but an obscure figure doing a lowly job, saving to realize a dream. The prince (Naveen) is the one who is spoiled and has to learn a lesson. Each can help the other grow.

But in other ways, this story is in keeping with the original tale. Frogs are often looked upon with disgust and contempt; alligators (not, of course, present in the original scenario) are feared as big, dangerous, sharp-toothed predators. Well, one should not be so quick to judge. Maybe that scary saurian is really a talented musician. That frog there is a graceful dancer, the other one is a fine vegan cook with big dreams. (She is a frog because her kiss, instead of turning the enchanted frog back into a prince, instead turned her into an amphibian too.)

There is a lot of cooking going on in this film, all of it vegan, with the mincing of mushrooms and other vegetables fostering character development. Three dimwitted human hunters try to catch the two frogs in order to cook and feast on their legs, but they are defeated and humiliated. Once again, there is no pre-eminence of a human above a beast--although, of course, the amphibious pair are really enchanted humans. However, this fact reinforces rather than weakens the anti-hunting message. Few will seriously consider that the animals hunters want to kill and eat might be enchanted or reincarnated humans, but at least viewers will be more inclined to look at matters from the victims' point of view.

There are other important messages. The poor but hard-working Black waitress who dreams of being a chef is more worthy of honor than the lazy aristocrat who's had everything handed to him on a platter all his life and wasted it, until now, disinherited, he aims to marry for money. Loyalty and determination are more important than success and wealth and power. The best True Love is built on friendship. Skin color - whether a golden light brown, a rich mahogany brown, a rosy peach, or green - is unimportant; it's what is inside that counts. Even the lowliest firefly is worthy of Love.

There are other important messages. The poor but hard-working Black waitress who dreams of being a chef is more worthy of honor than the lazy aristocrat who's had everything handed to him on a platter all his life and wasted it, until now, disinherited, he aims to marry for money. Loyalty and determination are more important than success and wealth and power. The best True Love is built on friendship. Skin color - whether a golden light brown, a rich mahogany brown, a rosy peach, or green - is unimportant; it's what is inside that counts. Even the lowliest firefly is worthy of Love.

These reflections do not mean, however, that this story is top-heavy with Important Messages. It is a funny entertainment, a musical delight (jazz in 1912 New Orleans, Cajun music in the bayou), an adventure bordering on other worlds, an uplifting romance. There are also some scary shadow-demons that could prove too much for timid little ones (I know they would have sent me diving under the seats when I was a small kid). Anxious conservative types --the kind who want to ban Harry Potter--will probably be offended by all the magic and witchcraft, both evil (Facilier the sorcerer who turns the prince into a frog) and good (Mama Odie the Vodun priestess who succeeds in uniting the lovers, and thus facilitates the bridal kiss that returns them to human shape).

The Grimm brothers' story never explain how or why the prince was enchanted into a frog in the first place. This one does. Facilier transformed him for malignant, selfish reasons--but he would not have been able to do it had not the prince been an indolent, rather arrogant wastrel. Yet even Naveen had good qualities and was able to teach the heroine some important lessons that helped her to become a better human being (not to mention that he enabled her to become a princess).

We recommend this movie especially to those who love jazz and good-versus-evil stories with happy endings--in fact everybody except the rigid and the timid. The rest of us will be gifted with a good time and a new appreciation for frogs and fireflies.

-Benjamin Urrutia

Book Review: Eating Animals

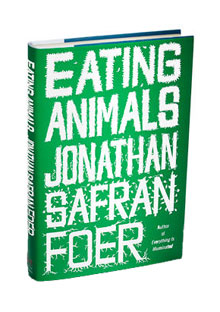

Jonathan Safran Foer. Eating Animals. New York: Little, Brown & Co. 342 pages (including 61 pages of annotated references). Hardcover. $25.99

Jonathan Foer, who has won prizes, critical acclaim and international popularity with his novels, now turns to nonfiction with a book that is a powerful indictment of the evils that factory farming inflicts on animals, on humans, and on planet Earth. His two-word title already uncovers truth not usually faced, reminding readers that we are unthinkingly devouring living creatures. "We have waged war, or rather let a war be waged, against all of the animals we eat. The war is new and has a name: factory farming." (p.33). It is also a war against the environment, against our health, against our children, against future generations. (And yet it is only a new, intensified version of a very old war, as William Cowper's 1785 poem The Task declared: "Earth groans beneath the burthen of a war / Waged [against] defenseless innocence.")

Jonathan Foer, who has won prizes, critical acclaim and international popularity with his novels, now turns to nonfiction with a book that is a powerful indictment of the evils that factory farming inflicts on animals, on humans, and on planet Earth. His two-word title already uncovers truth not usually faced, reminding readers that we are unthinkingly devouring living creatures. "We have waged war, or rather let a war be waged, against all of the animals we eat. The war is new and has a name: factory farming." (p.33). It is also a war against the environment, against our health, against our children, against future generations. (And yet it is only a new, intensified version of a very old war, as William Cowper's 1785 poem The Task declared: "Earth groans beneath the burthen of a war / Waged [against] defenseless innocence.")

As part of his self-introduction, Foer describes the obsession of his grandmother, a survivor of the Holocaust/Shoah, with food: even in her nineties she saves coupons, hoards quantities of food she could never consume, asks anxiously about every grandchild's weight. During the Nightmare she had fled interminably, alone, always with Nazis hovering around and behind; eating what scraps she could beg or find, getting weaker and sicker. When she was near death on one of the final days, a kind Russian offered her a piece of pig meat. But she turned it down. For all she knew, it might save her life, but "If nothing matters, there's nothing to save." (p. 17) Foer was raised in an extended family in which we tell stories and remember, we don't kick the dog, we care for one another. Things do matter. But the family also ate animals, and for years he participated, rather uncomfortably, most of the time. When he became a father, he knew he had to find out the truth, tell the story, and live by what he learned.

The book gives the reader a chance to "look aside" and see that which has been made invisible. If it's all right to eat animals, why not dogs? There are countless unwanted ones around. But, as Foer reflects, he himself wouldn't eat his beloved dog George, and it's safe to assume that none of his readers would do such a thing. Yet people in other nations do. Does it make sense, he asks, that we kill millions of unwanted dogs and cats and "render" them into food for cows and pigs that we do eat--pigs that are just as intelligent, affectionate, and playful as dogs?

The book gives the reader a chance to "look aside" and see that which has been made invisible. If it's all right to eat animals, why not dogs? There are countless unwanted ones around. But, as Foer reflects, he himself wouldn't eat his beloved dog George, and it's safe to assume that none of his readers would do such a thing. Yet people in other nations do. Does it make sense, he asks, that we kill millions of unwanted dogs and cats and "render" them into food for cows and pigs that we do eat--pigs that are just as intelligent, affectionate, and playful as dogs?

In one of the most memorable stories in the book, the author describes an adventure in company with a heroic woman, a converted slaughterhouse worker, who carries out nonviolent raids on factory farms, little compassionate sorties in the great war. The two of them crept one night into a poultry factory, finding many sheds locked. Why? Birds cannot turn doorknobs . . . The pair finally found an unlocked shed full of turkey chicks perhaps two weeks old, many living, many already dead. She rescued a few who were suffering badly but could survive; one, who was clearly too far gone to be moved, she quickly killed. This she does only rarely, and it always hurts her. She welcomed the chance to have her story told; she wants the public to know why so many of the doors are locked, why the horrors we pay for are kept out of sight.

Foer has other, very different figures he admires, such as two small-firm farmers who try diligently to keep life decent for their pigs and chickens until they send them to the killing floor. But they can't control every aspect, or avert the final grief and terror, and still make a living. Ironically, one of them was recently kicked out of the mini-firm he headed because his colleagues decided that his humane policies were cutting too much into profits. Foer does not condemn those who conscientiously take this path, but finds it inherently contradictory to take care for the feelings of beings one is ultimately treating as things to be eaten. The more consistent path--the path he himself chooses--is vegetarianism.

Prominent rabbis, we learn, have spoken out strongly against the abuses of the factory farm system, especially after the news broke of cruelties at a kosher plant in Iowa. Anyone involved in such atrocities while claiming to be kosher is committing nothing less than blasphemy (page 69). That these rabbis have thus protested is much to their credit. At the same time, the reader is aware that many rabbis have not wanted to know such things, and most Jews still eat flesh without asking questions. The situation is perhaps even worse with Christian clergy; those who speak up are few, though one or two, like the Rev. Andrew Linzey, have had a considerable influence. The vast majority of Christians not only eat (factory-farmed) flesh, but when challenged defend their practice with scripture. What right do we of this tradition have to call ourselves followers of the compassionate Christ while eating food which, we could easily learn, was produced with abysmal and systematic cruelty?

This book has already had great impact, as reflected in TV interviews and reviews in major periodicals. If it were up to me (Benjamin), it would be read in synagogues and temples every Shabbath and in churches every Sunday. It should be required reading for every adult carnivore and omnivore and all those on the fence. However, I do not recommend some chapters for young children, for vegetarians of tender sensibilities, or for people who are eating - no matter what they are eating.

Much of the data in this book is available elsewhere, but Foer offers new insights worthy of reflection. He also contributes much new knowledge. One gem: "Half a century before Plymouth, early American settlers celebrated a Thanksgiving with the Timicua Indians in what is now Florida . . . " These settlers were of course from Spain. The Spanish and the Timicua dined on bean soup for this first celebration (p. 250). We would do well to imitate them, if we want our Thanksgivings to be historically authentic!

The sixty-one pages of references contain much additional information; they should be skimmed, if not studied.

--Benjamin Urrutia and Gracia Fay Ellwood

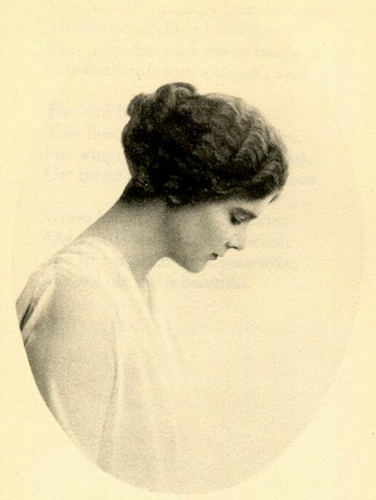

Pioneer: Gustav Holst, 1874-1934

Gustavus Theodore von Holst was born in Cheltenham, England, in 1874, to a musical family of Swedish descent. His mother Clara was a pianist and singer; his father Adolph was a piano teacher, organist, and choirmaster. Gustav's early life was unhappy. Clara, a sweet, gentle person, died when he was only eight, and Adolph, absorbed in his piano, neglected the sensitive boy's emotional needs and multiple health problems. Gustav studied piano and violin, but a neurological disorder in his right hand made prolonged practice painful. (Later he gave up both instruments in favor of the trombone, which he could play in bands and orchestras for a living).

Gustavus Theodore von Holst was born in Cheltenham, England, in 1874, to a musical family of Swedish descent. His mother Clara was a pianist and singer; his father Adolph was a piano teacher, organist, and choirmaster. Gustav's early life was unhappy. Clara, a sweet, gentle person, died when he was only eight, and Adolph, absorbed in his piano, neglected the sensitive boy's emotional needs and multiple health problems. Gustav studied piano and violin, but a neurological disorder in his right hand made prolonged practice painful. (Later he gave up both instruments in favor of the trombone, which he could play in bands and orchestras for a living).

When Gustav was ten or eleven his father married his former piano student Mary Stone. Holst's later practice of vegetarianism and interest in  Hinduism may have been influenced by Mary, a member of the then-new movement of Theosophy, which draws heavily upon Hinduism and other Eastern religions. Gustav listened as Mary and others talked of reincarnation. Quite possibly he first heard of vegetarianism from her, because Theosophy encourages it as an expression of its ideal of harmlessness toward all beings.

Hinduism may have been influenced by Mary, a member of the then-new movement of Theosophy, which draws heavily upon Hinduism and other Eastern religions. Gustav listened as Mary and others talked of reincarnation. Quite possibly he first heard of vegetarianism from her, because Theosophy encourages it as an expression of its ideal of harmlessness toward all beings.

Gustav began composing in his teens. Thanks to the critical success of one of these early compositions, his father borrowed money to send him to the Royal College of Music in London when he was nineteen. As soon as he left home he became a vegetarian; in hopes of improving his health, his daughter tells us. She takes little interest in vegetarianism, and does not tell us if his motivation later deepened, or indeed if he sustained it throughout his life. But there are reasons to suspect that both were the case. In London he soon made connections that would have supported a compassionate diet. He joined the Hammersmith Socialist Society led by William Morris, and for a time directed the society's choir. A number of those in the British Socialist movement were concerned not only about class injustice but gender and species injustice as well, and consequently ate no meat. Thus when he listened to lectures by George Bernard Shaw, who was outspokenly vegetarian (See the "Pioneer" column in GBS PT issue 24) it seems likely that Gustav was sometimes enlarging his mind regarding the animal concern. He also became an ardent enthusiast for Wagner's music, and so may have become acquainted with Wagner's concern for animal suffering; the issue appears both in Wagner's writings and in the plot of Parsifal. The Wikipedia article on Holst describes him as having "a passion for vegetarianism," suggesting that the commitment was lasting. In any case, there is no doubt that he was a very caring person of powerful and sometimes embarrassing integrity. One of his student friends wrote "I feel that the evil and scandal in the world must put its tail between its legs when it meets you."

Actually, Holst's vegetarian lifestyle at first worsened his health problems, both his weak vision and his painful hand, because the cheap-boarding-house meals he was served as a student were already inadequate, and he (like Gandhi in his London student days a few years earlier) did not get enough nourishing food. But Holst was unworldly and paid little attention to the problem; money was scarce, and he made do with nuts.

He made a rather odd-looking figure. He was shy, thin, anemic, and very nearsighted; he had grown an unfashionable beard; and his rather unfortunate wardrobe included a "preposterous Inverness coat" that was far too big for him. Yet he was brilliant, and deeply interested in people as well as music and unconventional ideas.  Considering his peculiar appearance, when he fell in love with a new member of the Socialist choir, a very young and beautiful soprano named Isobel Harrison, is is to the credit of both that she perceived the fine jewel in the odd setting, and responded to his love. They became engaged. Expensive gifts were out of the question, but he wrote her a new love song every week. She persuaded him to eat better, shave off his beard, and dress more acceptably. Gustav loved

visiting Isobel's family, who, unlike his own self-absorbed father, were as warm-hearted and generous as she was. (Marriage had to wait until 1901 when he became a teacher and their finances improved somewhat. In 1907 they had one daughter, Imogen, who was to become her father's biographer as well as a fine composer and conductor.)

Considering his peculiar appearance, when he fell in love with a new member of the Socialist choir, a very young and beautiful soprano named Isobel Harrison, is is to the credit of both that she perceived the fine jewel in the odd setting, and responded to his love. They became engaged. Expensive gifts were out of the question, but he wrote her a new love song every week. She persuaded him to eat better, shave off his beard, and dress more acceptably. Gustav loved

visiting Isobel's family, who, unlike his own self-absorbed father, were as warm-hearted and generous as she was. (Marriage had to wait until 1901 when he became a teacher and their finances improved somewhat. In 1907 they had one daughter, Imogen, who was to become her father's biographer as well as a fine composer and conductor.)

Also during this student period Holst developed a profound and long-lasting interest in India and Hindu religion, especially its basic affirmation of ultimate oneness, which undergirds the widespread Hindu practice of vegetarianism. This interest very likely supported his commitment to his own diet. He studied Sanskrit and gained enough facility to translate some hymns of the Rig Veda, for which he wrote musical settings. He wrote several other Hindu-themed works as well, including an opera.

Holst's world was one in which supernormal powers and reincarnation were as real as the most everyday sights and sounds. Around 1912 he became absorbed in astrology, which, although it is part of the Hindu worldview, only came alive for him in its Western form, thanks to his friend Clifford Bax. It made very good sense to Holst that human lives and everything else on earth are intertwined with the rest of the universe, and that one way this would manifest is in the planets' influence on us. He enjoyed casting his friends' horoscopes, which he found insightful. But of course the great  fruit of Holst's astrology is his 1914-1916 suite The Planets. Especially in "Neptune, the Mystic," he presents us with what has been called "one of the most awe-inspiring intimations of the Infinite ever registered." As Holst once wrote to a friend, "Everything in this world . . . is just one big miracle. Or rather, the universe itself is one."

fruit of Holst's astrology is his 1914-1916 suite The Planets. Especially in "Neptune, the Mystic," he presents us with what has been called "one of the most awe-inspiring intimations of the Infinite ever registered." As Holst once wrote to a friend, "Everything in this world . . . is just one big miracle. Or rather, the universe itself is one."

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

Sources: Gustav Holst: A Biography by Imogen Holst, and online essay by Ian Lace.

The actual scenario in nearly all cases is only too well known. The parent spoons pureed flesh into the infant's mouth; when the child is old enough to ask where it comes from, she will hear a highly sanitized and conscience-numbing answer. If she still shows any disturbing vegetarian inclinations, the parent will probably pressure her to give them up via one or more of what Melanie Joy calls "the Three Ns": eating meat is Normal, Natural, and Necessary. Growing up, the child will find the Three Ns reinforced from every side.

The actual scenario in nearly all cases is only too well known. The parent spoons pureed flesh into the infant's mouth; when the child is old enough to ask where it comes from, she will hear a highly sanitized and conscience-numbing answer. If she still shows any disturbing vegetarian inclinations, the parent will probably pressure her to give them up via one or more of what Melanie Joy calls "the Three Ns": eating meat is Normal, Natural, and Necessary. Growing up, the child will find the Three Ns reinforced from every side. Animal corporations also wield their influence apart from government. In Diet for a New America John Robbins shows that by giving out advertisements called "educational materials" to schools, the dairy, meat and egg boards brainwash virtually all citizens, from kindergarten on, into believing that their animal products are foundational to good health. Another example: the American Dietetic Association gives representatives of the dairy industry a major say in the formation of its dietary guidelines, which may have something to do with its recommendation to drink three glasses of cow milk per day. (Most persons of color are dairy-intolerant, but too bad.)

Animal corporations also wield their influence apart from government. In Diet for a New America John Robbins shows that by giving out advertisements called "educational materials" to schools, the dairy, meat and egg boards brainwash virtually all citizens, from kindergarten on, into believing that their animal products are foundational to good health. Another example: the American Dietetic Association gives representatives of the dairy industry a major say in the formation of its dietary guidelines, which may have something to do with its recommendation to drink three glasses of cow milk per day. (Most persons of color are dairy-intolerant, but too bad.)  The Courage to Become Free

The Courage to Become Free

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke  human bird roost, is frequently sentimentalized into a medieval hippie who wandered about shoeless, preaching to avians and wolves. Certainly he was a lover of animals, and a strong advocate of peace between humans and the rest of God's creation. But he no less favored peace between human factions in a violent age; even more significantly, he saw the connection between peace on both these fronts. He knew that the war of humans against animals, and wars between humans, ultimately stem from the same source; we will not have peace in one without peace in the other.

human bird roost, is frequently sentimentalized into a medieval hippie who wandered about shoeless, preaching to avians and wolves. Certainly he was a lover of animals, and a strong advocate of peace between humans and the rest of God's creation. But he no less favored peace between human factions in a violent age; even more significantly, he saw the connection between peace on both these fronts. He knew that the war of humans against animals, and wars between humans, ultimately stem from the same source; we will not have peace in one without peace in the other.

This animated dramatization of the fairy tale takes a number of liberties with the Grimms' narative, bringing home its message of illusion and true worth in new and refreshing ways. This princess (Tiana) is not a spoiled brat but an obscure figure doing a lowly job, saving to realize a dream. The prince (Naveen) is the one who is spoiled and has to learn a lesson. Each can help the other grow.

This animated dramatization of the fairy tale takes a number of liberties with the Grimms' narative, bringing home its message of illusion and true worth in new and refreshing ways. This princess (Tiana) is not a spoiled brat but an obscure figure doing a lowly job, saving to realize a dream. The prince (Naveen) is the one who is spoiled and has to learn a lesson. Each can help the other grow.  There are other important messages. The poor but hard-working Black waitress who dreams of being a chef is more worthy of honor than the lazy aristocrat who's had everything handed to him on a platter all his life and wasted it, until now, disinherited, he aims to marry for money. Loyalty and determination are more important than success and wealth and power. The best True Love is built on friendship. Skin color - whether a golden light brown, a rich mahogany brown, a rosy peach, or green - is unimportant; it's what is inside that counts. Even the lowliest firefly is worthy of Love.

There are other important messages. The poor but hard-working Black waitress who dreams of being a chef is more worthy of honor than the lazy aristocrat who's had everything handed to him on a platter all his life and wasted it, until now, disinherited, he aims to marry for money. Loyalty and determination are more important than success and wealth and power. The best True Love is built on friendship. Skin color - whether a golden light brown, a rich mahogany brown, a rosy peach, or green - is unimportant; it's what is inside that counts. Even the lowliest firefly is worthy of Love.  Jonathan Foer, who has won prizes, critical acclaim and international popularity with his novels, now turns to nonfiction with a book that is a powerful indictment of the evils that factory farming inflicts on animals, on humans, and on planet Earth. His two-word title already uncovers truth not usually faced, reminding readers that we are unthinkingly devouring living creatures. "We have waged war, or rather let a war be waged, against all of the animals we eat. The war is new and has a name: factory farming." (p.33). It is also a war against the environment, against our health, against our children, against future generations. (And yet it is only a new, intensified version of a very old war, as William Cowper's 1785 poem The Task declared: "Earth groans beneath the burthen of a war / Waged [against] defenseless innocence.")

Jonathan Foer, who has won prizes, critical acclaim and international popularity with his novels, now turns to nonfiction with a book that is a powerful indictment of the evils that factory farming inflicts on animals, on humans, and on planet Earth. His two-word title already uncovers truth not usually faced, reminding readers that we are unthinkingly devouring living creatures. "We have waged war, or rather let a war be waged, against all of the animals we eat. The war is new and has a name: factory farming." (p.33). It is also a war against the environment, against our health, against our children, against future generations. (And yet it is only a new, intensified version of a very old war, as William Cowper's 1785 poem The Task declared: "Earth groans beneath the burthen of a war / Waged [against] defenseless innocence.")  The book gives the reader a chance to "look aside" and see that which has been made invisible. If it's all right to eat animals, why not dogs? There are countless unwanted ones around. But, as Foer reflects, he himself wouldn't eat his beloved dog George, and it's safe to assume that none of his readers would do such a thing. Yet people in other nations do. Does it make sense, he asks, that we kill millions of unwanted dogs and cats and "render" them into food for cows and pigs that we do eat--pigs that are just as intelligent, affectionate, and playful as dogs?

The book gives the reader a chance to "look aside" and see that which has been made invisible. If it's all right to eat animals, why not dogs? There are countless unwanted ones around. But, as Foer reflects, he himself wouldn't eat his beloved dog George, and it's safe to assume that none of his readers would do such a thing. Yet people in other nations do. Does it make sense, he asks, that we kill millions of unwanted dogs and cats and "render" them into food for cows and pigs that we do eat--pigs that are just as intelligent, affectionate, and playful as dogs?  2 cups organic unbleached flour

2 cups organic unbleached flour Gustavus Theodore von Holst was born in Cheltenham, England, in 1874, to a musical family of Swedish descent. His mother Clara was a pianist and singer; his father Adolph was a piano teacher, organist, and choirmaster. Gustav's early life was unhappy. Clara, a sweet, gentle person, died when he was only eight, and Adolph, absorbed in his piano, neglected the sensitive boy's emotional needs and multiple health problems. Gustav studied piano and violin, but a neurological disorder in his right hand made prolonged practice painful. (Later he gave up both instruments in favor of the trombone, which he could play in bands and orchestras for a living).

Gustavus Theodore von Holst was born in Cheltenham, England, in 1874, to a musical family of Swedish descent. His mother Clara was a pianist and singer; his father Adolph was a piano teacher, organist, and choirmaster. Gustav's early life was unhappy. Clara, a sweet, gentle person, died when he was only eight, and Adolph, absorbed in his piano, neglected the sensitive boy's emotional needs and multiple health problems. Gustav studied piano and violin, but a neurological disorder in his right hand made prolonged practice painful. (Later he gave up both instruments in favor of the trombone, which he could play in bands and orchestras for a living).  Hinduism may have been influenced by Mary, a member of the then-new movement of Theosophy, which draws heavily upon Hinduism and other Eastern religions. Gustav listened as Mary and others talked of reincarnation. Quite possibly he first heard of vegetarianism from her, because Theosophy encourages it as an expression of its ideal of harmlessness toward all beings.

Hinduism may have been influenced by Mary, a member of the then-new movement of Theosophy, which draws heavily upon Hinduism and other Eastern religions. Gustav listened as Mary and others talked of reincarnation. Quite possibly he first heard of vegetarianism from her, because Theosophy encourages it as an expression of its ideal of harmlessness toward all beings.  Considering his peculiar appearance, when he fell in love with a new member of the Socialist choir, a very young and beautiful soprano named Isobel Harrison, is is to the credit of both that she perceived the fine jewel in the odd setting, and responded to his love. They became engaged. Expensive gifts were out of the question, but he wrote her a new love song every week. She persuaded him to eat better, shave off his beard, and dress more acceptably. Gustav loved

visiting Isobel's family, who, unlike his own self-absorbed father, were as warm-hearted and generous as she was. (Marriage had to wait until 1901 when he became a teacher and their finances improved somewhat. In 1907 they had one daughter, Imogen, who was to become her father's biographer as well as a fine composer and conductor.)

Considering his peculiar appearance, when he fell in love with a new member of the Socialist choir, a very young and beautiful soprano named Isobel Harrison, is is to the credit of both that she perceived the fine jewel in the odd setting, and responded to his love. They became engaged. Expensive gifts were out of the question, but he wrote her a new love song every week. She persuaded him to eat better, shave off his beard, and dress more acceptably. Gustav loved

visiting Isobel's family, who, unlike his own self-absorbed father, were as warm-hearted and generous as she was. (Marriage had to wait until 1901 when he became a teacher and their finances improved somewhat. In 1907 they had one daughter, Imogen, who was to become her father's biographer as well as a fine composer and conductor.)  fruit of Holst's astrology is his 1914-1916 suite The Planets. Especially in "Neptune, the Mystic," he presents us with what has been called "one of the most awe-inspiring intimations of the Infinite ever registered." As Holst once wrote to a friend, "Everything in this world . . . is just one big miracle. Or rather, the universe itself is one."

fruit of Holst's astrology is his 1914-1916 suite The Planets. Especially in "Neptune, the Mystic," he presents us with what has been called "one of the most awe-inspiring intimations of the Infinite ever registered." As Holst once wrote to a friend, "Everything in this world . . . is just one big miracle. Or rather, the universe itself is one." SHE has danced for leagues and leagues,

SHE has danced for leagues and leagues,