Editorial: The Prophet From Nazareth

Jesus and the Vegetarian Question

One of the issues debated among religious vegetarians and animal-eaters is the question "Was Jesus was a vegetarian?" It is true that for some animal defenders, the question is unimportant; Jesus has played little or no role in their lives, and there are other looming contemporary issues that take up their time and attention. But in fact the question matters for all of us who care about our animal cousins, because the figure of Jesus is pivotal for millions of Christians. How we interpret the texts about him dealing with this issue makes a difference to the progress of our Concern.

For Christians who hold that every part of the Bible gives us models for our own lives, the answer to the question is a confident no. They find scenes in the gospels that show Jesus helping some of his followers to make a successful catch of fish, or multiplying fish (and bread) to feed thousands of people in the wilderness, or eating a piece of fish during a Resurrection appearance. They conclude that because Jesus ate fish and encouraged his followers to do so, the Bible gives a stamp of approval to meat-eating.

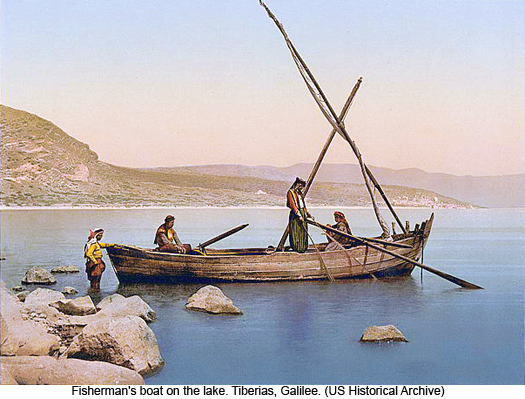

But those from the Christian tradition who do not see every passage of the Bible as necessarily authoritative for our lives may come to different conclusions. In a past issue of PT, it was suggested that even if Jesus did in fact accept fish-eating, his stance was not necessarily applicable to us because of major cultural differences between his situation and ours. He was ministering to peasants who were near the edge of subsistence or being pushed over it as a result of heavy taxation by Roman authorities and the Temple priesthood; in many instances they were losing their family farm plots as a result of crushing tax debt. If those living near the lake could catch some fish for their family, it might help them survive. (Those who earned a living by fishing were also being exploitatively taxed.)

Our situation as middle-class people in the twenty-first century is entirely different. We have many kinds of plant foods available; not only do we not need to fish (or hunt) to survive, we should know that commercial fishing and fish-farming are decimating the oceans at an alarming rate, just as factory-farming of land animals is bringing havoc to soils, groundwater, streams, lakes, and the atmosphere. Thus Jesus' stance regarding fish is no more binding on us than is his manner of dress. In fact, the pervading biblical theme that the world belongs to God, whose tender mercies are over all God's works, would rather require that we abstain from foods that threaten the earth and cause unnecessary suffering to animals.

Another view derives from the fact that a number of early Christians were vegetarian, specifically the Ebionites (meaning "the Poor,") who survived for several centuries and claimed Jesus' brother James as their spiritual forebear and the designated leader of the church after Jesus' departure. The Ebionites traced their vegetarian discipline to James, and quoted him as deriving it from the teachings of Jesus himself, whom they viewed as primarily a Hebrew prophet concerned with justice to the oppressed, both human and animal. (For more on this issue, see the Pioneer essay on James in PT 10 , May 2005.)

Jesus' Focus

In the canonical gospels, Jesus occasionally speaks caringly of animals; he says that God is conscious of the fall of every sparrow; he compares God's (and/or his own) longing to renew disordered Jerusalem with a hen's desire to gather her chicks under her wings. The fourth gospel includes a discourse in which he uses the ancient shepherd-sheep image to express the depths of divine love: "The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep." But Jesus' preaching and actions are mostly concerned with human beings. He denounces oppression; he has good news for the poor and exploited; he teaches listeners to be compassionate as God is compassionate. His central theme is that the Kingdom of God is in their midst. Thus animals are not really the objects in his prophetic message; however, it does have important implications for animals, as we shall see.

Roots of the Kingdom of God

Many readers may not know how far back in Hebrew tradition the Kingdom of God theme is rooted. Its seeds are found in the account of the establishment of the Covenant between God and Israel at Sinai, and beyond that in the Exodus, Israel’s foundational story. God is the Liberator who brings Israel out of Egypt, out of the house of bondage to a foreign emperor; and this God, who cares for the lowly and the oppressed, is to be Israel’s only ruler. The nature of the Covenant is complicated, with laws of many sorts, not all of them life-giving, formulated at various times. But the provisions that were almost surely central in the oral scriptures of the poor villagers aimed at economic justice: to safeguard each family’s inherited plot, and prevent families from being ruined by indebtedness and exploitation. They were based on God's loving and liberating compassion for the least among God's people.

In a later century, the prophet Samuel speaks out of this theme when the elders of the people ask for a king to lead them in war against the invading Philistines. Samuel resists, reiterating that God is to be their only monarch, and warning them that a king will become an exploiter: “He will take your sons . . . he will take your daughters . . . he will take your fields . . . he will take a tenth of your produce . . .” (I. Sam. 8:11-15) But God, with evident reluctance, tells him to give the petitioners what they request. (However, it is likely that many of the people were suspicious of this risky innovation.)

The second king, David, is described as “a man after God’s own heart,” and a royal/messianic theme arises in which justice is established through human kingship (as seen, for example, in some of the Psalms), a theme naturally promoted in royal and aristocratic circles. But this theme exists in tension with many of the common people’s commitment to the original state of affairs, a realm ruled by God only. And with good reason; already with David's son Solomon, who established a mini-empire, oppression had returned. Samuel’s warning that “he will take. . . he will take . . . he will take . . . ” in fact characterizes many of the kings as they are described by the chroniclers: they become the new Pharaohs of their day. In such situations, prophets arise to denounce, among other things, the oppression of the poor by the ruling royal and aristocratic powers of their time, and call the king and the people to return to God. The alternative will be disaster.

The second king, David, is described as “a man after God’s own heart,” and a royal/messianic theme arises in which justice is established through human kingship (as seen, for example, in some of the Psalms), a theme naturally promoted in royal and aristocratic circles. But this theme exists in tension with many of the common people’s commitment to the original state of affairs, a realm ruled by God only. And with good reason; already with David's son Solomon, who established a mini-empire, oppression had returned. Samuel’s warning that “he will take. . . he will take . . . he will take . . . ” in fact characterizes many of the kings as they are described by the chroniclers: they become the new Pharaohs of their day. In such situations, prophets arise to denounce, among other things, the oppression of the poor by the ruling royal and aristocratic powers of their time, and call the king and the people to return to God. The alternative will be disaster.

The disasters that do in fact befall Israel, namely, being conquered and exploited by one rising empire after another, are interpreted by later prophets as the result of earlier sins. They seek to find meaning in these catastrophes and sufferings by tracing them to covenant-breaking acts; they call the people to return to God. In certain passages they denounce the imperial oppressor, promising a new Exodus and a renewal of broken Israel. In some cases this renewal is to take place under an ideal Davidic king, sometimes under the compassionate and just rule of God only.

Jesus' Renewal of the Kingdom Proclamation

Jesus’ ministry must be seen as a part of this long kingdom-of-God tradition. He appears as a prophet in a situation in which the Roman rulers, their governors or client-kings such as Herod Antipas, and the collaborating priests of the Jerusalem temple (the High Priest was the Roman governor’s appointee) all demanded shares of the of the subsistence farmers who made up perhaps ninety percent of the population. Under this crushing triple tax burden, the village life in which most Galileans and Judeans lived was disintegrating. Unable to pay mounting tax debts, pursued by anxiety, many formerly self-subsistent families were losing their farm plots to the Romans and becoming day-laborers or worse.

Many of Rome's oppressed subjects may have fallen into despair and apathy, but because of the Jews' tradition of a compassionate and liberating God, there was strong resistance: this situation was not simply the Way Things Are. Festering frustration and rage were expressed in various ways, some covert, the most conspicuous being banditry and periodic violent revolts. These the dreaded Roman goon squads, the Legions, smashed with merciless ferocity: burning villages and even whole cities, enslaving or crucifying the fleeing inhabitants. Rome’s glorious empire was based on a protection racket.

Jesus’ prophetic renewal of the ancient message that a compassionate and just God is Israel’s only king is thus politically and economically subversive. It means that Caesar, who takes . . . and takes . . . and takes . . . and claims he is Son of God and therefore divinely authorized, is neither god nor king. Jesus message was that the kingdom of God comes by the unfaithful-faithful finding Immanuel, God’s giving, forgiving, and liberating presence, in their midst. By implication, they need not resort to the corrupted Temple, no longer a house of prayer but (as in Jeremiah's day) a den of robbers. Where the stresses of hunger and anxiety have led to alienation, abuse, and in-fighting in the villages, he calls for renewal of Covenant principles: share your bread (in communal meals); forgive the debts your neighbor owes you; lend to your neighbor in trouble; embarrass the hostile neighbor who insulted you with a slap on the face by turning the other cheek. Reach out even to the Roman soldier who demands that you carry his gear for a mile by carrying it for two miles.

The stories of Jesus' actions also proclaim the Kingdom of God. When he casts out multiple demons called Legion (!) from a homeless, psychotic man, and the Legion flees into pigs who rush into the water and drown, his hearers would understand that God would cause the shock-troops of the new Pharaoh to meet the same fate as those of the Exodus. (Since pigs can in fact swim, the details of this story need not be taken as literal history.) Stories of sea-crossings followed by the feeding of thousands in the wilderness also proclaimed that their one and only Monarch, who had once brought them out of bondage, fed them in the wilderness on manna, and given them the land, was at work through a new Moses. Stories of healings and a raising of the recently dead proclaim the presence of a new Elijah, renewing God’s rule in a time of apostasy and royal tyranny. (In confirmation, Moses and Elijah appear together with Jesus in the Transfiguration story).

The Cost of the Kingdom Proclamation

During his traveling ministry among the peasant villages of Galilee Jesus has skirmishes with the scribes and experts in the written Scriptures who function as retainers for the wealthy Temple elite (Jesus' message is probably based on the oral Scriptures of the illiterate poor). But when he goes to Jerusalem and makes a public, symbolic attack on the corrupted Temple itself, he is speaking Truth to Power--loudly. As a result, the chief priests and their bedfellows the Romans put him to the torturous death of a subversive: public crucifixion, Rome’s form of state terrorism. Some authorities think that the fact that no attempt was made to round up his followers is probably because Jesus’ message was nonviolent.

One of the reasons the political-economic dimensions of this message are hard to discern in the gospels is that the oral traditions that preserved it were probably not recorded until after the huge, hellish catastrophe, the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, that crushed the Judean revolt of

66-70 C.E. (Mark was perhaps written down just around 70). During the succeeding years, Rome used its shining victory over the uppity Judeans in a blame-the-victim propaganda campaign. In this paranoid atmosphere, it became dangerous to identify with or support anything Judean; and the message of a crucified Jew was highly suspect by its very nature. Thus the subversive nature of the Kingdom of God proclamation was muted and downplayed, and some victim-blaming becomes part of the gospel story. For example, the brutal, ruthless Pilate (eventually recalled by Rome for ill-judged force) is presented as a well-meaning sort who wanted to release Jesus, and a Judean mob easily manipulated by the chief priests is shown demanding his crucifixion--both very unlikely. Needless to say, this dishonest defensive strategy was to bear poisonous fruit for many centuries.

The Prophetic Principle and Animals

The concept of the Kingdom of God was preached to villagers who might have been more or less capable of governing themselves, if only the gougers would leave them alone. But though their small, partially self-subsistent communities would then have been much better off than under the heel of Empire, they would still have been oppressive to women; and some might still have depended on animals as tools.

However, the work of the prophets, and in this case that of Jesus, does contain the seeds of liberation for both women and animals nonetheless. An important prophetic principle is illustrated by the Kingdom teaching in Matt. 23:9, " call no man your father on earth, for you have one Father, who is in heaven; neither be called masters . . . ", which implies a profound critique of patriarchy not clearly evident in earlier prophetic writings. The prophetic principle in question is that all social interactions are to be judged by the criteria of God's justice and compassion for all. But no single prophet can speak to all situations. Any one prophet may denounce a pattern of injustice and its attendant violence without seeing or acknowledging others. As we noted in the April 07 PT, "in the Exodus narrative the Israelites' lambs, and the horses of the Egyptions, are seen as disposable. Yet the core of the prophetic critique remains, a divine gift out of which later prophets are called to develop, correct, and deepen the message of earlier ones." See Slaves to Pharaoh .

By calling for the enactment of God's justice and compassion for our oppressed animal cousins, and especially when we demonstrate compassion as we call for it, we are showing ourselves to be true daughters and sons of the prophets--for Christians, especially of the prophet from Nazareth.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

Sources: The Prophetic Imagination by Walter Brueggeman; Jesus in Context by Richard Horsley; God and Empire by John Dominic Crossan; Jesus by Marcus Borg; Sexism and God-Talk by Rosemary Radford Ruether; The Lost Religion of Jesus by Keith Akers, and other works.

The picture of King David is a detail from a stained-glass window by William Morris.

Unset Gems

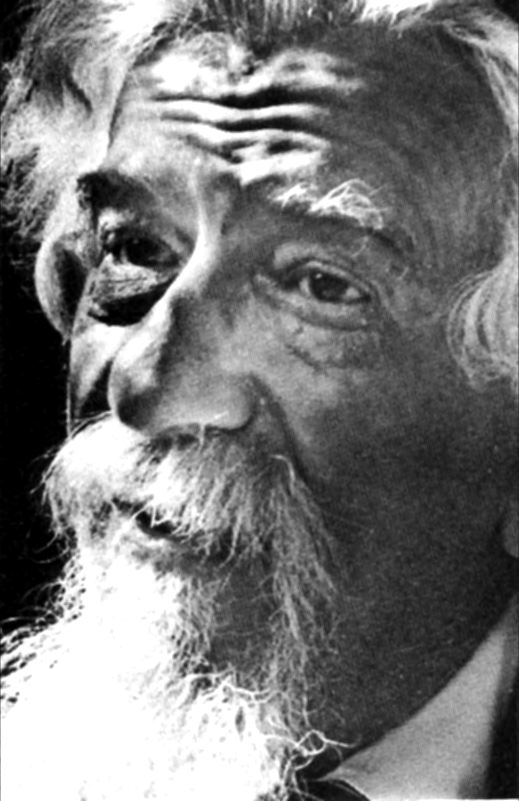

"Few are guilty; all are responsible . . . The prophet's word is a scream in the night. While the world is at ease and asleep, the prophet feels the blast from heaven "--Abraham J. Heschel, The Prophets

"Few are guilty; all are responsible . . . The prophet's word is a scream in the night. While the world is at ease and asleep, the prophet feels the blast from heaven "--Abraham J. Heschel, The Prophets

"Sin, like some powerful astringent, contracted [the human] soul to the very small dimensions of selfishness; and God was forsaken, and fellow-creatures forsaken, and man retired within himself . . . ." --Jonathan Edwards, 1703-1758

"To [C.S. Lewis], all animals were "who," not "that," and either "he" or "she," never "it, writes Katrelyn Angus in the April 2010 Reader's Digest. (This is not invariably true; animals are sometimes "it" in The Horse and His Boy.) Rudyard Kipling also treated animals with grammatical respect. Mother Wolf, and all female animals, are always "she," while Father Wolf and all male animals are always "he." Even the villain Shere Khan is "the tiger who [not "that"] lived by the Waingunga River."

--Contributed by Benjamin Urrutia

The photo is of Biblical scholar and civil rights activist Abraham Heschel.

It is not often that a physician writes a book about a feline as a respected colleague, indeed a colleague who is by now undoubtedly more famous as a caregiver than he. But that is the case with Oscar, resident cat at the Steere House Nursing Center in Providence, Rhode Island, where he holds court on the ward dedicated to patients with Alzheimer's and other forms of serious senile dementia, many of whom were approaching life's closure. Oscar was the subject of a flurry of media articles and presentations three years ago, celebrating the animal's seemingly uncanny ability to sense when a patient was about to die. The furry attendant insisted on being with that person, cuddling up to him or her and purring in the last hours, not leaving until the mortician came to remove the body. (See the NewsNote

It is not often that a physician writes a book about a feline as a respected colleague, indeed a colleague who is by now undoubtedly more famous as a caregiver than he. But that is the case with Oscar, resident cat at the Steere House Nursing Center in Providence, Rhode Island, where he holds court on the ward dedicated to patients with Alzheimer's and other forms of serious senile dementia, many of whom were approaching life's closure. Oscar was the subject of a flurry of media articles and presentations three years ago, celebrating the animal's seemingly uncanny ability to sense when a patient was about to die. The furry attendant insisted on being with that person, cuddling up to him or her and purring in the last hours, not leaving until the mortician came to remove the body. (See the NewsNote  companion only increasing. Dr. Dosa was at first skeptical, inclined to make light of staff members who reported their observation of the cat's unusual activity. But as he observed patients over time he too could not help noticing how often Oscar was on target in knowing when his unique mission was called for, often before medical personnel had detected that the end of life was imminent. As Dosa interviewed a number of survivors of Oscar's earlier ministrations, in every case he found confirmation of the cat's remarkable ministry.

companion only increasing. Dr. Dosa was at first skeptical, inclined to make light of staff members who reported their observation of the cat's unusual activity. But as he observed patients over time he too could not help noticing how often Oscar was on target in knowing when his unique mission was called for, often before medical personnel had detected that the end of life was imminent. As Dosa interviewed a number of survivors of Oscar's earlier ministrations, in every case he found confirmation of the cat's remarkable ministry.

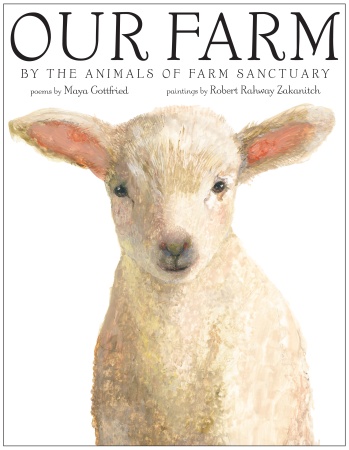

Maya Gottfried imaginatively and empathetically gives voice to her friends at Farm Sanctuary in a collection of poems, each featuring its "author:" Maya, a cow, also known as Grandmama Moo, the kind matriarch. Mayfly, a gentlebird of a rooster, whose motto is "ladies first." J. D., a piglet who loves to run. Gabriella, an open-minded hen. Clarabell, a nanny goat who likes to roam and wander. Four lively ducklings. Ramsey, a cautious ram. Whisper, a turkey who loves to dance. Bonnie, a peace-loving donkey. Violet, a pig who believes she is a flower. Ari and Alicia, twin kids (goat-type). Whitaker, a friendly calf. Diego, an incredibly beautiful duck.Cece and Barnaby, rabbits. Hilda, a very sweet sheep. Her poem is my favorite of the book. It feels like a prayer: "Thank you to the wind that cools..."

Maya Gottfried imaginatively and empathetically gives voice to her friends at Farm Sanctuary in a collection of poems, each featuring its "author:" Maya, a cow, also known as Grandmama Moo, the kind matriarch. Mayfly, a gentlebird of a rooster, whose motto is "ladies first." J. D., a piglet who loves to run. Gabriella, an open-minded hen. Clarabell, a nanny goat who likes to roam and wander. Four lively ducklings. Ramsey, a cautious ram. Whisper, a turkey who loves to dance. Bonnie, a peace-loving donkey. Violet, a pig who believes she is a flower. Ari and Alicia, twin kids (goat-type). Whitaker, a friendly calf. Diego, an incredibly beautiful duck.Cece and Barnaby, rabbits. Hilda, a very sweet sheep. Her poem is my favorite of the book. It feels like a prayer: "Thank you to the wind that cools..." Serves 8 (serving size about ¾ cup)

Serves 8 (serving size about ¾ cup) . . . . More things are wrought by prayer

. . . . More things are wrought by prayer