Editorial: "From the Animals' Point of View"

By Robert Ellwood

George Orwell's famous short novel, Animal Farm, is generally, and rightly, considered a satire of the Russian revolution and its subsequent takeover by bureaucratic elites of the Communist party. These ruthless officials then maintained themselves in a privileged position through police-state tactics mixed with rousing propaganda, leaving the masses about as enslaved as before, except they could now sing about their freedom. (It goes without saying, at least for those who know much about George Orwell, that this remarkably honest and independent thinker was just as telling against institutions of his own ancestral England; he despised cant and hypocrisy whether from East or West, North or South.)

In the story the animals of Manor Farm join together and overthrow the exploitative regime of Farmer Jones, and begin operating the farm themselves under the name Animal Farm. But step by step the pigs, considered the most capable and intellectual of the new stakeholders, concern themselves with filling out endless forms and other paperwork rather than physical labor, take the best food for themselves because of their need for intellectual vigor, betray and destroy the heroes of the revolution, and finally don clothes and move into Farmer Jones' own house, restoring the name Manor Farm.

Animal Farm was written in 1943. Orwell had a hard time finding a publisher, because Britain was then allied with the Soviet Union against Hitler, and the satire was sensitive. Four leading publishers turned it down; one, though their readers were enthusiastic, ran it by the Ministry of Information. A Ministry official responded:

Another thing: it would be less offensive if the predominant caste in the fable were not pigs. I think the choice of pigs as the ruling caste will no doubt give offence to many people, and particularly to anyone who is a bit touchy, as undoubtedly the Russians are.

The book was finally published in August 1945, three months after the end of the war in Europe, and as the Cold War was just beginning to appear on the horizon.

Orwell himself looked at the parable in a somewhat different light from the Information Ministry official, though others have also regretted the choice of pigs as the "heavies." He said, in a later preface intended for an émigré Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm:

I proceeded to analyze Marx's theory from the animals' point of view. To them it was clear that the concept of a class struggle between humans was pure illusion, since whenever it was necessary to exploit animals, all humans united against them: the true struggle is between animals and humans.

This comment is reminiscent of the Animal Kinship Committee's booklet "Are Animals Our Neighbors? Taking the View From Below." The question is not "How do those in power see the situation" but "How do the victims see it?" They will be honest. As the story begins, Old Major, pig and revolutionary prophet to the animals, could not have put it more plainly:

Now comrades, what is the nature of this life of ours? Let us face it, our lives are miserable, laborious and short. We are born, we are given just so much food as will keep the breath in our bodies, and those of us who are capable of it are forced to work to the last atom of our strength; and the very instant that our usefulness has come to an end we are slaughtered with hideous cruelty. No animal in England knows the meaning of happiness or leisure after he is a year old. No animal in England is free. . .

Man is the only creature that consumes without producing. He does not give milk, he does not lay eggs, he is too weak to pull the plough, he cannot run fast enough to catch rabbits. Yet he is lord of all the animals. He sets them to work, he gives back to them the bare minimum that will prevent them from starving, and the rest he keeps for himself. . .You cows that I see before me, how many thousands of gallons of milk have you given during this last year? And what has happened to that milk which should have been breeding up sturdy calves? Every drop of it has gone down the throats of our enemies. . .

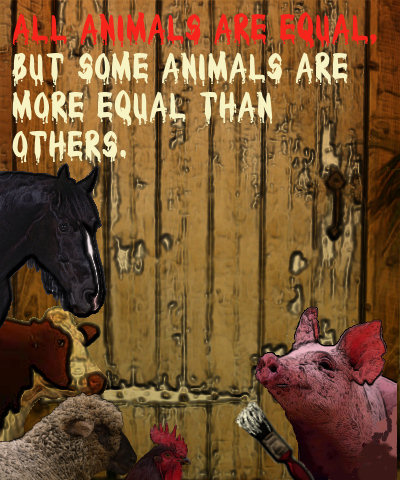

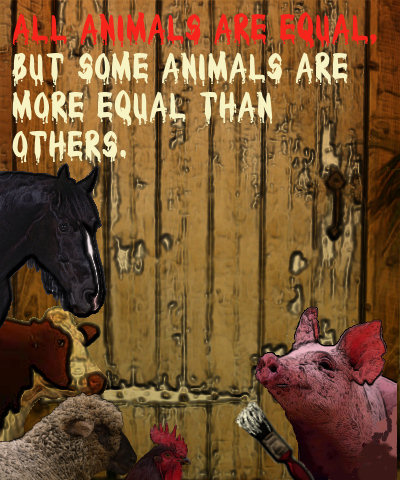

And much more in the same vein. All is summarized in the animals' Seven Commandments which the pigs write up after the successful Revolution. They include: 1, Whatever goes upon two legs in an enemy; 2, Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend; and finally, 7, All animals are equal.

In the early days of liberty, these principles are really and joyfully lived out, though not always in a self-aware manner. For example, the sheep, like true believers in many a cause, reduced these words to thoughtless cant, and "often as they lay in the field they would all start bleating 'Four legs good, two legs bad! Four legs good, two legs bad!' and keep it up for hours on end, never growing tired of it." This mindlessness puts their new liberty in danger.

We see the animals' point of view. But let us, for just a moment, recall Farmer Jones' viewpoint. In his own mind, he does not murder the animals for their flesh, he slaughters, or perhaps harvests their meat. He does not sell or eat the flesh of pigs, cows, or sheep, but rather he dines on, or trades in, pork, beef, mutton, and their subvariants such as hams and steaks. His language expressed his numbness and self-deception. Unfortunately, these traits can return, for the animals' honest language can morph into its opposite. The clever pigs, by the time they re-established a tyrannical regime very like the original one, had also taken up Jones' viewpoint, though veiling their words with the language of liberation (and, of course, unconsciously showing their own bad faith): they changed the last Commandment to "All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others."

Orwell himself was very interested in the way in which language, in particular choices of words and the employment of euphemisms for unpleasant topics, affects not only how we communicate with others but, more profoundly, how we think in the privacy of our own minds. For the language we use easily becomes interiorized, so that we talk to ourselves also in whatever degree of bluntness or euphemism we wish, and forget how to think in any other way. Orwell's best-known novel of all, 1984, is about a dystopia that communicates in Newspeak, a language so cunningly devised that it was impossible not only to talk, but even to think, anything contrary to the official ideology. In it, propaganda is always truth, and war is always peace.

Newspeak may not yet have taken hold everywhere, even though it is now decades after 1984, but its footprints are more than evident in many spheres. In a fine 1946 essay, "Politics and the English Language," Orwell made such observations as that, "The inflated style is itself a kind of euphemism. A mass of Latin[ate] words falls upon the facts like soft snow, blurring the outlines and covering up all the details." We are familiar with such military and bureaucratic expressions as "surgical strikes," "soft targets," "enhanced interrogation techniques," "pacification," "acceptable losses," and the unforgettable "mistakes were made." Those who carry out or support the goals of the military or bureaucracies in question do not talk, even to themselves, about the massacres or torture they are committing or defending.

I would however suggest that nowhere is Newspeak more active today, as it has been for a long time, than in the relationship of the English language to farmed animals and the products stolen from them. One can think to oneself as well as tell others -- especially one's children -- that packaged and processed meat is something in a Food Group, and not think at all about the quivering flesh with its streaming gore hanging up on the hook. One can go through life without really knowing, because one does not really want to know, that beef is taken from the corpse of a brutally killed dead cow, or pork from a dead (or dying) pig. Our dual English heritage makes it easy: the names of several of the flesh products on our table are from Norman French, while the corresponding animals bear Anglo-Saxon names. But the real point is that the Newspeak euphemism makes it easier--even "natural"--to eat them, just as it is easier to "pacify" or "liquidate" humans we consider enemies than to murder them.

Orwell was far-sighted. We ought to look at things from the animals' point of view, and turn Newspeak back into honest Plain Speech.

For a review of "Are Animals Our Neighbors?" click on View . This booklet is available cost-free from the editor. For larger quantities, donations are encouraged. See small print below for address.

Unset Gems

"In a time of deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act." --George Orwell

"The human body has no more need for cows’ milk than it does for dogs’ milk, horses’ milk, or giraffes’ milk."--Michael Klaper, MD

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

"There will come a time...when civilized people will look back in horror on our generation and the ones that preceded it: the idea that we should eat other living things running around on four legs, that we should raise them just for the purpose of killing them! . . ." --Dennis Weaver (1924 –2006), American actor

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

"God has created a multi-eyed and multi-feeling world that is, as it were, felt by the Spirit from within." --Andrew Linzey

News Notes

Green Foods Resolutions

In October 2009, the small town of Signal Mountain, Tennessee, became the first community in the country to pass a Green Foods Resolution. It encouraged increased commitment to vegetarianism as well as other ecological measures relating to diet. Alexandria, Virginia became the second community to pass a Green Foods Resolution in March 2010. Additional resolutions are now pending in New York city, where Farm Sanctuary is a key member of the Foodprint Alliance, and in several other municipalities across the nation.

--Farm Sanctuary website

Pro-Bull Protest in Madrid

On the 28th of March 2010 there was a march of several thousand protesters (most of them young) in Spain's capitol, demanding the abolition of bull "fighting." The marchers shouted the slogan "La tortura no es cultura," "Torture is not culture." The regional government of Catalonia, the northeastern region of Spain, has already restricted bullfighting and is seriously considering the complete abolition of the bull ring. All this would have seemed incredible just a few decades ago. See Madrid March

- Contributed by Benjamin Urrutia

Eat Beef, Kill Horses

Tens of thousands of wild mustangs and other horses are rounded up through cruel and deadly drives, and then locked in tiny pens where they waste away in captivity, to clear grassland for cattle raising. Moreover, pregnant mares and young foals are vulnerable to these round-ups and often die. To watch footage and learn more about this issue, see Roundups .

Letters

Dear Peaceable Friends,

Dear Peaceable Friends,

The meat-heavy diet common in the U.S. today is deeply rooted in our history (though the present factory-farming system is relatively new).

The main food eaten by Americans in the 1800s was meat, & the most common drinks were coffee & whiskey. Most men drank hard liquor; this was a strong custom, with those who refrained from alcohol usually being members of the temperance movement. A common breakfast consisted of eggs, corn meal cakes, meat stew, & fried potatoes. Dinner, served in the early afternoon, was the main meal. A typical menu was a meat and/or fish dish, potatoes, sometimes a stewed vegetable, and a dessert of pudding. Supper was lighter than dinner, but similar in menu. The abundance of "game," fish, and fowl in America allowed this kind of meat-heavy diet in rural areas, especially on the frontier. Interestingly, sourdough bread was a staple among the gold miners in California. Sometimes dried fruit was taken on the trail.

Of course, food varied in different locations and among social classes. Wealthy Victorian-era folk in cities ate a rich diet of meat, carbohydrates, stewed and boiled vegetables, desserts, cheese, and dried fruit. Poor city dwellers ate lots of potatoes & bread. Diet also varied amongst ethnic groups, especially in methods of preparation. New Englanders tended to boil meat and vegetables, Southerners to fry them. Slave diets usually consisted of pork fat, bacon, & corn meal. (When this is taken together with the severe stresses of their lives, it is no wonder that their life expectation was only about thirty.)

Vegetarianism existed in nineteenth-century America, but was not common. The Rev. William Metcalfe and other members of the vegetarian Bible Christian Church immigrated from England in 1817 and established themselves in Philadelphia. The New England Transcendentalists, including the Alcotts, usually practiced vegetarianism (Louisa May's father Bronson was strongly committed to a nonviolent diet, but her mother Abba sometimes ate meat). Many Shakers also refrained from eating meat. Shaker communes left the choice to the individual; their dining halls were divided into those who ate a "bloodless" diet & those who had a "regular" diet. For the most part, their meals were very nutritious with lots of fresh fruit & vegetables, which they grew themselves. As a testament to their balanced way of eating, most Shakers lived into their seventies & many into their nineties.

Outside of communes, vegetarianism was practiced sparsely, because most people thought that they would die if they did not eat meat. However, an American Vegetarian Society was formed in 1850 by Sylvester Graham, a convert of William Metcalfe and creator of the Graham cracker (originally made with coarse flour and little sweetening). From about mid-century onward, the Seventh Day Adventist church, under the leadership of Ellen G. White, required their members to refrain from meat consumption, for reasons both of compassion and health. (About half of Adventists are vegetarian today.)

This is only a brief overview of American diets in the nineteenth century; its actual history is long and complex.

Barbara Booth

Barbara Booth, pictured in one of her period costumes, teaches history at Santa Ana College in California, where she uses photos and videos of period dances and historical re-enactments as visual aids. For her Pilgrimage story in the January, '09 PT, see Barbara B

Dear Peaceable Friends,

. . . . The letter from Linda Terry about the risks of hugging adult tigers did indeed point out an aspect of the kinship of human with beast which must be considered at all times. The recent death of a trainer at Sea World Florida at the "hands" of a killer whale underscores the point perfectly.

I always enjoy the book reviews. Making Rounds With Oscar sounds like a real tearjerker, and it explores a remarkable phenomenon as well. It does make one wonder, though: what about when Oscar decides just to spend an afternoon with a person? How long does it take before his visit is seen as the death knell? Maybe I'd not be so comfortable having him visit me!

The cream of beet soup sounds great. I love beets, which are generally an underappreciated vegetable. . . . .

--Carl Sheppard

David Dosa, the author of the Oscar book, explains that Oscar is generally not an affectionate kitty. He visits all the residents on his ward, but sits coolly on a chair or windowsill. Only when a person is dying does he curl up next to her or him and stay until after death. In these cases, when Oscar begins his vigil the person is already in an altered state of consciousness. Thus there is, fortunately, no confusion or apprehension about the meaning of Oscar's visits.

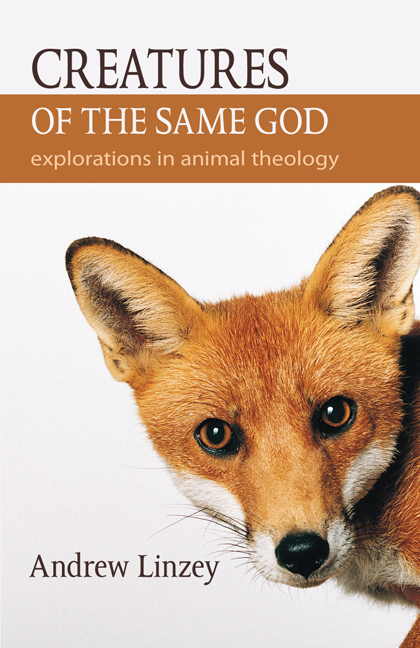

Book Review: Creatures of the Same God

Creatures of the Same God: Explorations in Animal Theology by Andrew Linzey. NY: Lantern Books, 2007, 2009. xx & 139 pp. $20.00 paperback.

This book presents eight of Linzey's recent essays on animal themes, together with an Introduction, "They're Only Animals, for Heaven's Sake!" It also includes an appendix, "An Open Letter to the Bishops on Hunting," originally published in 2002.

This book presents eight of Linzey's recent essays on animal themes, together with an Introduction, "They're Only Animals, for Heaven's Sake!" It also includes an appendix, "An Open Letter to the Bishops on Hunting," originally published in 2002.

The titles of the essays are: "Religion and Sensitivity to Animal Suffering," "Theology as If Animals Mattered," "Animal Rights and Animal Theology," "The Conflict Between Ecotheology and Animal Theology," "Responding to the Debate About Animal Theology," "Jesus and Animals: A Different Perspective," "Animals and Vegetarianism in Early Chinese Christianity," "On Being an Animal Liturgist," and "Summing Up: Towards a Prophetic Church for Animals."

All these essays carry forward in some way Linzey's basic theological theme, that we are to model our dealings with animals on the Divine generosity manifest in the Incarnation. As God pours Godself out in service to the weak, the wounded, and the needy, we are to serve, protect, and heal animals, rather than treating them as existing to serve our needs and wants. "The Good Shepherd lays down his life for the sheep." In fact we owe animals more than compassion: as creatures of God and recipients of God's care, they are owed our respect as well. He accepts the language of animal rights, calling them "theos-rights."

To highlight just three of these essays: In the Introduction, Linzey sketches the incredulous response of his teachers and fellow students--"They're only animals!"-- to his concern with animal issues during his theological studies in the 1970s. This general incomprehension moved him to explore the rational basis of the animal concern, an important dimension he might not have emphasized otherwise. The Introduction also reflects on the animal movement today. While there is far greater awareness of the issues than in the 1970s, there are also serious flaws in the movement, such as a tendency to self-righteousness on the part of many. Linzey urges that we all acknowledge that we have participated in animal exploitation, and must make our appeals to the rest of the world with humility. He particularly deplores the small but highly visible minority who threaten or engage in violence, thereby undercutting the moral high ground which is so important to our message, and giving the media an excuse to condemn us all. Indeed, the violent approach is self-contradictory, for the heart of our appeal is to compassion for and kinship with all.

In the essay dealing with the conflict between ecotheology and animal theology, Linzey points out that, though the two movements have common areas, the conflicts are serious. One important one is that ecotheologists tend to affirm and celebrate all aspects of nature, including predation, as good; this is the way things ought to be. For example, Matthew Fox calls predation "the Eucharistic law of the Universe, even Divinity gets eaten in this world." We humans are not to question killing, but learn to "kill reverently." (Linzey points out that he doesn't apply this maxim to killing other humans.) One practical result is that many ecologists either do not adopt vegetarianism at all, or adopt it for environmental rather than ethical and compassionate reasons.

Besides Matthew Fox and one other thinker, Linzey cites Jay B. McDaniel as an example of an ecotheologian who affirms predation as God's will, the way things ought to be. However, in choosing McDaniel (with whom I am personally acquainted) to illustrate these problems of ecotheology, I am sure Linzey errs. McDaniel is an ethical/compassionate vegetarian; far from celebrating predation, he emphasizes its tragic nature, God's participation in all suffering, and God's work of inspiring or "luring" us to compassionate action toward transforming this world-tragedy to peace and unity. I venture to say that Linzey's and McDaniel's theologies share crucially important emphases, and that they are definitely allies. (For some quotations from McDaniel in an earlier issue of PT, see McDaniel .)

One of the most revelatory of Linzey's essays is "Animals and Vegetarianism in Early Chinese Christianity," which first appeared as an introduction to a Chinese edition of his Animal Gospel. Linzey describes a little-known Christian movement in western China during the Tang dynasty of the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries. The evidences of this movement appear in a stele or upright inscribed stone describing a Religion of Light in which God the creator took human form; a pagoda excavated in 1999 with, among other things, a depiction of the Nativity; and a number of manuscripts found in a cave early in the twentieth century, some of which (the "Jesus Sutras") allude to or even quote passages in the Gospels. Remarkably, one or another of the manuscripts refers to the Sacred Spirit's compassion for all beings, and to John the Baptist as a vegetarian; they urge respect for all living beings, forbidding taking the life of any. The language of this movement includes concepts clearly derived from Taoism and Buddhism, but that is not more surprising than that early Christians expressed aspects of their faith in concepts from Greek philosophy. It is encouraging to animal-caring Christians to see these signs that their concern is not, as some claim, the latest fad from the secular world, but has been shared by spiritual sisters and brothers far distant in time and space.

One of the most revelatory of Linzey's essays is "Animals and Vegetarianism in Early Chinese Christianity," which first appeared as an introduction to a Chinese edition of his Animal Gospel. Linzey describes a little-known Christian movement in western China during the Tang dynasty of the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries. The evidences of this movement appear in a stele or upright inscribed stone describing a Religion of Light in which God the creator took human form; a pagoda excavated in 1999 with, among other things, a depiction of the Nativity; and a number of manuscripts found in a cave early in the twentieth century, some of which (the "Jesus Sutras") allude to or even quote passages in the Gospels. Remarkably, one or another of the manuscripts refers to the Sacred Spirit's compassion for all beings, and to John the Baptist as a vegetarian; they urge respect for all living beings, forbidding taking the life of any. The language of this movement includes concepts clearly derived from Taoism and Buddhism, but that is not more surprising than that early Christians expressed aspects of their faith in concepts from Greek philosophy. It is encouraging to animal-caring Christians to see these signs that their concern is not, as some claim, the latest fad from the secular world, but has been shared by spiritual sisters and brothers far distant in time and space.

I am tempted to cite more treasures in this volume, such as a wonderful early Coptic account of Jesus healing a mule, but lack space. Overall, I recommend this book for all persons of faith who defend animals. Christians from evangelical and mainstream denominations will find it particularly supportive.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

Recipes

Peas and Corn Salad with Fresh Ginger

Serves 4

2 T. extra virgin olive oil

2 scallions, sliced

6 thin slices fresh ginger, peeled

1 clove garlic, minced

3 cups green peas, fresh or frozen (if using frozen, thaw first)

3 cups yellow corn, fresh or frozen (if using frozen, thaw first)

½ tsp. reduced sodium soy sauce

½ tsp. sea salt, or to taste

freshly ground black pepper, to taste

2 – 3 T. pine nuts, lightly toasted

1 T. chopped fresh cilantro

dash toasted sesame oil

In large skillet, warm olive oil. Sauté scallion and fresh ginger slices for one minute (medium-high heat); then add garlic and continue to cook for one more minute. Add peas, carrots, soy sauce, sea salt, and black pepper. Reduce heat, cover and cook until vegetables are tender – about 10 minutes. Remove from heat, stir in pine nuts, cilantro and toasted sesame oil. Serve over Jasmine rice or orzo pasta.

This is a cooked salad that is wonderfully refreshing with flavors of fresh ginger and cilantro. It’s perfect for a light springtime lunch or dinner. It is easy to toast pine nuts in a dry skillet over medium-low heat. Being careful not to burn the pine nuts; it only takes a minute or two to lightly toast them. Do not let them brown, or they will have a burnt flavor. Heat just until fragrant.

--- Angela Suarez

Adzuki Bean Salad

Serves 4 – 6

1 ½ cups adzuki beans, rinsed and soaked overnight

½ sweet onion (such as Mayan or Walla-Walla), finely chopped

1 carrot, grated

2 T. freshly snipped chives

2 T. chopped fresh parsley or cilantro

1 small clove garlic, minced

1 cup corn (fresh or thawed)

3 – 4 T. extra virgin olive oil

1 T. grated fresh ginger

1 T. fresh squeezed lemon juice

2 tsp. agave nectar

2 tsp. reduced sodium soy sauce

½ tsp. sea salt, or to taste

2 – 3 dashes toasted sesame oil

1 tsp. water

1 – 2 tsp. sesame seeds

cilantro, chives and/or chives for garnish

In 2 quart saucepan, cover adzuki beans with water; bring to boil. Reduce heat and cook until tender-- about 35 – 40 minutes. Remove from heat; drain and pour into serving bowl. Allow to cool for a few minutes. Then add onion, carrot, chives, parsley or cilantro, garlic and corn. Toss gently to mix ingredients well.

In a small bowl, whisk together olive oil, ginger, lemon juice, agave, soy sauce, sea salt, sesame oil and water. Pour over adzuki bean and corn mixture. Toss well to coat beans with dressing mixture. Garnish with sesame seeds and herbs. Serve over baby greens if desired.

This is a delicious recipe for using fresh cilantro and chives. The adzuki beans are sweet and nutty in flavor. They are a healthy component of a vegan diet: a good source of protein, iron and potassium. For more more information about this very tasty bean, see Adzuki .

--- Angela Suarez

Pioneer: Albert Einstein (1879-1955)

Albert Einstein is universally regarded as among the most eminent mathematicians and physicists of all time for his theory of relativity, his equation of mass and energy (e=mc2) and other epoch-making contributions to our knowledge of the universe.

Albert Einstein is universally regarded as among the most eminent mathematicians and physicists of all time for his theory of relativity, his equation of mass and energy (e=mc2) and other epoch-making contributions to our knowledge of the universe.

But Einstein was far more than a laboratory-bound scientist. He was an outspoken man of the world, becoming a deeply committed Gandhian pacifist (except for the war against Hitler with its attempted extermination of the Jewish people), a Zionist concerned about fairness for Palestinians, an opponent of capital punishment, and a defender of political and academic freedom. Not only that, but with his eccentric yet appealing character, rumpled clothes, wild hair, bicycling, and towering genius (exaggerated, if possible, in popular lore), he emerged in his post-1930 American years as a legendary figure, virtually a byword.

And throughout his life he was increasingly concerned about the issue of eating animal flesh, becoming a vegetarian in his last year or two. Here are the quotations. In a letter of Dec. 27, 1930:

Although I have been prevented by outward circumstances from observing a strictly vegetarian diet, I have long been an adherent to the cause in principle. Besides agreeing with the aims of vegetarianism for aesthetic and moral reasons, it is my view that a vegetarian manner of living by its purely physical effect on the human temperament would most beneficially influence the lot of mankind.

By August 3, 1953, in another letter, he could say:

I have always eaten animal flesh with a somewhat guilty conscience.

Less than a year later (and about a year before his death), he wrote in a letter of March 30, 1954:

So I am living without fats, without meat, without fish, but am feeling quite well this way. It almost seems to me that man was not born to be a carnivore.

Alice Calaprice, editor of The New Quotable Einstein (Princeton University Press, 2005, pp. 281-82), from which these lines are taken, asserts after the last that "Einstein was probably not a vegetarian by choice," but as a consequence of lifelong stomach problems. But it is odd that she should say this. Although the digestive issues may have been the initiating factor, both the temper and the content of several of his comments make it clear that more was involved. Clearly, the great man was also drawn to the ethical and, in his term, aesthetic, aspects of a plant-based diet. To him, even before he practiced it consistently, vegetarianism was a cleaner-feeling and more attractive way of life.

The word relativity, employed in Einstein's General and Special Theories of Relativity, is sometimes confused with moral relativism. But of course they are quite different. The former refers (to put it briefly and simplistically) to the apparent motion and gravitational pull of objects relative to the speed of light (the "cosmological constant" designated "c" in the famous equation), and to each other.

The word relativity, employed in Einstein's General and Special Theories of Relativity, is sometimes confused with moral relativism. But of course they are quite different. The former refers (to put it briefly and simplistically) to the apparent motion and gravitational pull of objects relative to the speed of light (the "cosmological constant" designated "c" in the famous equation), and to each other.

Moral relativism, the idea that one should derive one's ethical principles wholly from circumstances and "When in Rome, do as the Romans do," is entirely different. Einstein was not such a relativist, even though he recognized there are circumstances that demand hard choices and, occasionally, subordination of a valued principle to an even higher one. He renounced German citizenship and went to Switzerland as early as 1896 because of his dislike of German militarism. He continually opposed war and warlike preparations. But he came to allow that in the world as it is, war can sometimes be prevented only by organized opposition to warlike power, and by persuasive deterrence, ideally but not always that of Gandhian non-violence (Calaprice, 168-69). He wrote in 1953,

"I am a dedicated but not an absolute pacifist; this means that I am opposed to the use of force under any circumstances except when confronted by an enemy who pursues the destruction of life as an end in itself." (Calaprice, 161)

His 1939 letter to President Roosevelt warning, on the basis of information received from scientists in Europe, that Germany might soon develop an atomic bomb, is well known.

It is possible that throughout much of his life Einstein's stance toward the ideal of vegetarianism was somewhat similar. One may debate whether human war and consumption of animal flesh are really comparable, or whether some degree of moral relativism applies in hard cases. The quandary may appear one way to the front-line soldier in line of fire or the German Jew facing the "final solution," and another to an academic ethicist or a parliamentarian debating whether a particular war is "just." It may be one kind of issue to an ordinary vegetarian facing a difficult family Thanksgiving, and have been another to the turkey in the slaughterhouse.

In such a world, Einstein's great moral stature and willingness to confront the hard points honestly, whether or not one always agree, is an inspiration. He was not perfect. But he was a servant of truth as he saw it, whether scientific or social; he was willing to live his convictions, and he ended up vegetarian.

--Robert Ellwood

Our thanks to Virginia Iris Holmes for bibliographic guidance in the vast sea of Einstein studies.

Poetry: Mary Oliver

The Swan

Did you too see it, drifting, all night, on the black river?

Did you see it in the morning, rising into the silvery air -

An armful of white blossoms,

A perfect commotion of silk and linen as it leaned

into the bondage of its wings; a snowbank, a bank of lilies,

Biting the air with its black beak?

Did you hear it, fluting and whistling

A shrill dark music - like the rain pelting the trees - like a waterfall

Knifing down the black ledges?

And did you see it, finally, just under the clouds -

A white cross Streaming across the sky, its feet

Like black leaves, its wings Like the stretching light of the river?

And did you feel it, in your heart, how it pertained to everything?

And have you too finally figured out what beauty is for?

And have you changed your life?

The Peaceable Table is

a project of the Animal Kinship Committee of Orange Grove Friends Meeting, Pasadena, California. It is intended to resume the witness of that excellent vehicle of the Friends

Vegetarian Society of North America, The Friendly

Vegetarian, which appeared quarterly between 1982 and

1995. Following its example, and sometimes borrowing from its

treasures, we publish articles for toe-in-the-water

vegetarians as well as long-term ones.

The journal is intended to be

interactive; contributions, including illustrations, are

invited for the next issue. Deadline for the June issue

will be May 29, 2010. Send to graciafay@gmail.com

or 10 Krotona Hill, Ojai, CA 93023. We operate primarily

online in order to conserve trees and labor, but hard copy

is available for interested persons who are not online.

The latter are asked, if their funds permit, to donate $12 (USD) per year. Other

donations to offset the cost of advertising (in The Christian Century) are welcome.

Website: www.vegetarianfriends.net

Editor: Gracia Fay Ellwood

Book and Film Reviewers: Benjamin Urrutia & Robert Ellwood

Recipe Editor: Angela Suarez

NewsNotes Editors: Lorena Mucke and Marian Hussenbux

Technical Architect: Richard Scott Lancelot Ellwood

Dear Peaceable Friends,

Dear Peaceable Friends,

This book presents eight of Linzey's recent essays on animal themes, together with an Introduction, "They're Only Animals, for Heaven's Sake!" It also includes an appendix, "An Open Letter to the Bishops on Hunting," originally published in 2002.

This book presents eight of Linzey's recent essays on animal themes, together with an Introduction, "They're Only Animals, for Heaven's Sake!" It also includes an appendix, "An Open Letter to the Bishops on Hunting," originally published in 2002. One of the most revelatory of Linzey's essays is "Animals and Vegetarianism in Early Chinese Christianity," which first appeared as an introduction to a Chinese edition of his Animal Gospel. Linzey describes a little-known Christian movement in western China during the Tang dynasty of the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries. The evidences of this movement appear in a stele or upright inscribed stone describing a Religion of Light in which God the creator took human form; a pagoda excavated in 1999 with, among other things, a depiction of the Nativity; and a number of manuscripts found in a cave early in the twentieth century, some of which (the "Jesus Sutras") allude to or even quote passages in the Gospels. Remarkably, one or another of the manuscripts refers to the Sacred Spirit's compassion for all beings, and to John the Baptist as a vegetarian; they urge respect for all living beings, forbidding taking the life of any. The language of this movement includes concepts clearly derived from Taoism and Buddhism, but that is not more surprising than that early Christians expressed aspects of their faith in concepts from Greek philosophy. It is encouraging to animal-caring Christians to see these signs that their concern is not, as some claim, the latest fad from the secular world, but has been shared by spiritual sisters and brothers far distant in time and space.

One of the most revelatory of Linzey's essays is "Animals and Vegetarianism in Early Chinese Christianity," which first appeared as an introduction to a Chinese edition of his Animal Gospel. Linzey describes a little-known Christian movement in western China during the Tang dynasty of the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries. The evidences of this movement appear in a stele or upright inscribed stone describing a Religion of Light in which God the creator took human form; a pagoda excavated in 1999 with, among other things, a depiction of the Nativity; and a number of manuscripts found in a cave early in the twentieth century, some of which (the "Jesus Sutras") allude to or even quote passages in the Gospels. Remarkably, one or another of the manuscripts refers to the Sacred Spirit's compassion for all beings, and to John the Baptist as a vegetarian; they urge respect for all living beings, forbidding taking the life of any. The language of this movement includes concepts clearly derived from Taoism and Buddhism, but that is not more surprising than that early Christians expressed aspects of their faith in concepts from Greek philosophy. It is encouraging to animal-caring Christians to see these signs that their concern is not, as some claim, the latest fad from the secular world, but has been shared by spiritual sisters and brothers far distant in time and space. Albert Einstein is universally regarded as among the most eminent mathematicians and physicists of all time for his theory of relativity, his equation of mass and energy (e=mc

Albert Einstein is universally regarded as among the most eminent mathematicians and physicists of all time for his theory of relativity, his equation of mass and energy (e=mc The word relativity, employed in Einstein's General and Special Theories of Relativity, is sometimes confused with moral relativism. But of course they are quite different. The former refers (to put it briefly and simplistically) to the apparent motion and gravitational pull of objects relative to the speed of light (the "cosmological constant" designated "c" in the famous equation), and to each other.

The word relativity, employed in Einstein's General and Special Theories of Relativity, is sometimes confused with moral relativism. But of course they are quite different. The former refers (to put it briefly and simplistically) to the apparent motion and gravitational pull of objects relative to the speed of light (the "cosmological constant" designated "c" in the famous equation), and to each other.