Editorial: Jesus and Animals

By Robert Ellwood

Stories and sayings involving animals do not surround the figure of Jesus as much as, say that of St. Francis of Assisi or the Buddha, especially in the latter's previous lives, or even the Prophet Muhammad and his beloved cat, Muezza. Yet they are there, and some are very significant. We will here just present a representative sampling, saving fuller discussion for later.

Accounts in the Canonical Gospels

"Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? And not one of them will fall to the ground without your Father knowing it." (Matt. 10:29) "It [the Kingdom of God] is like a grain of mustard seed which a man took and sowed in his garden; and it grew and became a tree, and the birds of the air made nests in its branches." (Luke 13:19) These sayings tell us that that which is small and little-regarded by society nevertheless has value to God, potential for greatness.

"I am the Good Shepherd. The Good Shepherd lays down his life for the sheep." (John 10:11) By society's standards, it is almost always the sheep whose life the owner takes to benefit himself; but God is working to turn our upside-down world right.

And, in congruence with this statement, we have the parable of the lost sheep: a shepherd with a hundred sheep goes after one that was lost, "and when he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders, he calls together his friends and his neighbors, saying to them, 'Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep which was lost.'" (Luke 15: 3-7)

And the seemingly ungracious metaphorical words of Jesus to the Greek Syrophoenician woman who had asked him to heal her daughter: "Let the children first be fed, for it is not right to take the children's bread and throw it to the dogs,"But she replies, "Yes, Lord; yet even the dogs under the table eat the children's broken pieces." And Jesus' more gracious reply: "For this saying you may go your way; the demon has left your daughter." (Mark 7:27-29) Jesus seems to have been willing to learn a great lesson from this woman about the breadth of God's love for humans; perhaps for animals also?

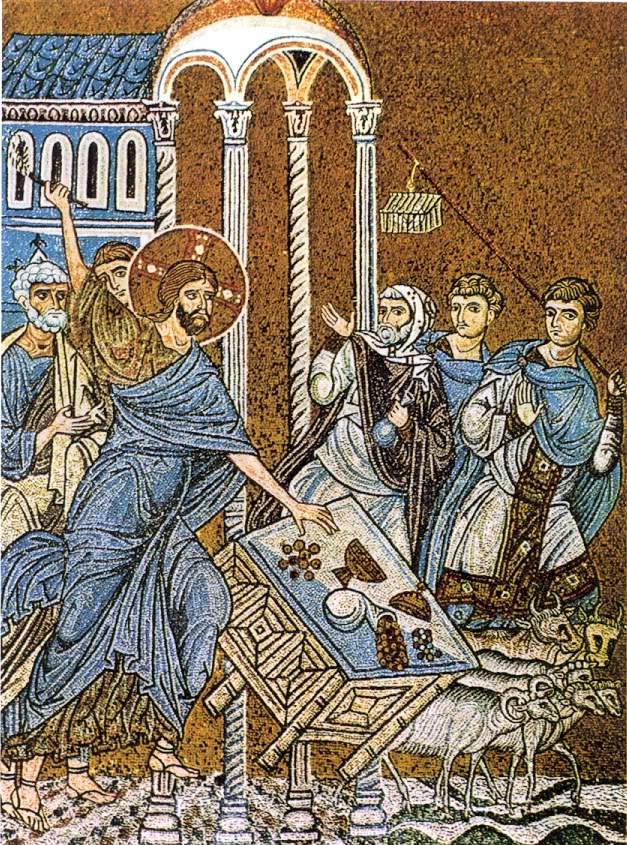

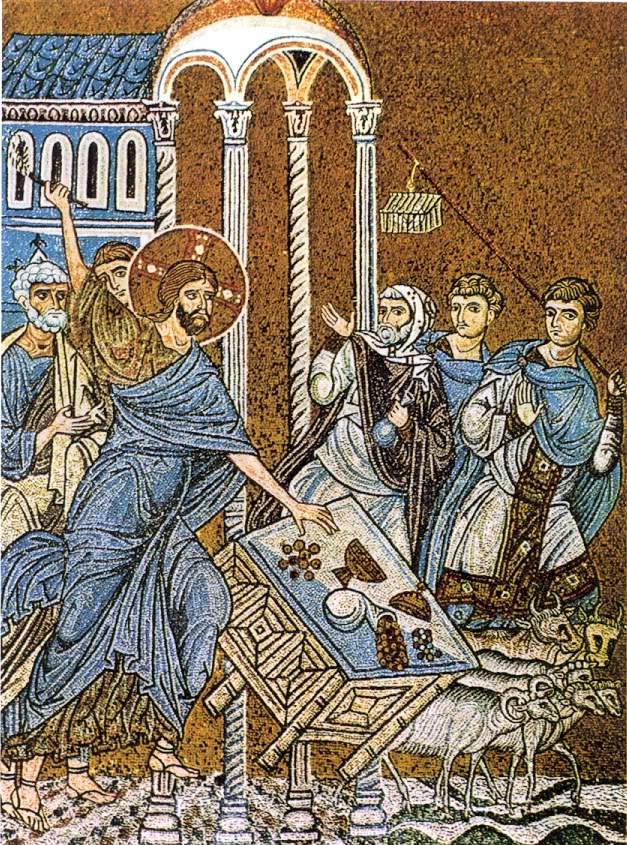

Then, in his Jerusalem ministry, we see the overturning of the tables of the moneychangers, and the chairs of those who sold pigeons for sacrifice (notice that he doesn't knock over the tables with the confined birds on them!)-- (Mark 11:15) -- and climatically, the entry in the Holy City on the back of a donkey. Matthew tells us "this took place to fulfill what was spoken by the prophet (Zechariah, 9:9), saying

Tell the daughter of Zion

Behold, your king is coming to you.

humble, and mounted on an ass,

and on a colt, the foal of an ass."

G.K. Chesterton wrote a fine poem, which has always been a favorite of mine, put in the mouth of that donkey. The narrator describes him- or her-self as born under strange omens, as monstrous, but as having a wondrous secret: there was an hour, fiercely sweet, when he bore the Christ. (See The Donkey .

These sayings and narratives all have in common an implicit recognition of subjective feeling on the part of the bird or animal -- the sparrow's fate is known to God, the dogs are fed -- whether or not that is the main point. The Good Shepherd image is even revolutionary. Against them must be set others in which that is not the case. Interestingly all these latter cases involve larger bodies of water, and a farming and fishing society's instrumental view of animals is presupposed. Possibly the ultimate background is the ancient Near-Eastern tendency to view the sea-- including fresh-water seas like Galilee -- as representing chaos, as it were creation not yet fully formed, and potentially threatening to swallow up that which has form. These latter incidents are all miracle-stories, generally involving nature as well as healing; some might consider them parables acted out by Jesus.

The first and perhaps most important symbolically is the incident in the country of the Gerasenes, where Jesus met a man possessed of many demons called "Legion"--significantly, the name of a basic detachment of Roman troops. Jesus cast them out, liberating the man; whereupon the demons begged him not to send them into the abyss, but to let them enter a herd of swine nearby. He gave them leave to do so, and then "the herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake and were drowned." (Luke 8:26-33) Thus, like Pharaoh's horsemen in the Exodus, the Legion is swallowed by the sea as the oppressed victim is liberated. As we have pointed out before in PT, this story need not be taken as history, one reason being that in fact pigs can swim.

Another cluster of incidents, all having to do with fish as caught for food: in debate over whether Jesus should pay taxes, the teacher implied that he need not, but so as "not to give offense," told Peter to catch a fish from the sea, "and when you open its mouth you will find a shekel; take that and give to them for me and for yourself." (17: 24-27). (Most mainline New Testament scholars agree that this story is also nonhistorical.) Then there is the famous story of feeding the five thousand in the wilderness with five loaves and two small fish (Matt. 14:17 ff.), echoing Israel's extended founding story of being fed in the wilderness by God. Lastly, in the final chapter of the Gospel of John, we find the account the miraculous draught of fishes. The resurrected Lord, standing at daybreak on the banks of the Sea of Tiberias, called out to the disciples who were fishing in a boat, asking if they had caught anything. When they said they had not, Jesus told them to throw their net on the other side of the boat. It was suddenly so full of fish they could not haul it on board, but had to drag it to shore, "full of large fish, a hundred and fifty-three of them." (Commentators suppose that number must have some significance, but to the best of my knowledge no one is sure what it is.) There they met Jesus, with bread and frying fish over a charcoal fire for their breakfast--a story that echoes and affirms pre-Resurrection accounts, such as Luke 5: 3-7, of Jesus helping his fisherman disciples. (John 21: 4-13)

Apocryphal Accounts

We may now turn to animal narratives in apocryphal literature about Jesus. Some of these are quite interesting. The Infancy Gospel of Thomas, for example, tells us that as a small child, Jesus made sparrows out of clay, then gave them life so that the flew away. This story, with its allusion to the Creation acount, incidentally, is picked up by the Qur'an even though it is not in any of the canonical Christian gospels: "I have come to you with a sign from your Lord. I will create for you out of clay as the likeness of a bird; then I will breathe into it, and it will be a bird, by the leave of God." 1

The Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, which was popular in the Middle Ages, perhaps influencing the placement of domestic animals in Christmas Nativity scenes, tells us that when the newborn Jesus was placed in the stable, the ox and the ass continually adored him. Later, while traveling, Mary and Joseph with Jesus and other children met a dragon, which caused the other children to flee. But Jesus was unafraid and met the dragon, who worshiped him. Jesus said to his fearful parents, "Do not be afraid; and do not consider me to be a child, for I am and always have been perfect; and all the beasts of the forest must needs be docile before me." 2

Most impressive of all is a story from a Coptic fragment, of unknown background but certainly from ancient times. It is worth recording in full: "It happened that the Lord left the city and walked with his disciples over the mountains. And they came to a mountain, and the road which led up it was steep. There they found a man with a pack-mule. But the animal had fallen, because the man had loaded it too heavily, and now he beat it, so that it was bleeding. And Jesus came to him and said, 'Man, why do you beat your animal? Do you not see that it is too weak for its burden, and do you not know that it suffers pains?' But the man answered and said, 'What is that to you? I may beat it as much as I please, since it is my property, and I bought it for a good sum of money. Ask those who are with you, for they know me and they know about this.' And some of the disciples said, 'Yes, Lord, it is as he says. We have seen how he bought it.' But they Lord said, 'Do you then not see how it bleeds, and do you not hear how it groans and cries out?' But they answered and said, 'No, Lord, that it groans and cries out, we do not hear.' But Jesus was sad and exclaimed, 'Woe to you, that you do not hear how it complains to the Creator in heaven and cries out for mercy. But threefold woes to him about whom it cries out and complains in its pain.' And he came up and touched the animal. And it stood up and its wounds were healed. But Jesus said to the man, 'Now carry on and from now on do not beat it any more, so that you too may find mercy.' " 3

Andrew Linzey, in Creatures of the Same God, opines that though this story is not from the first century, it may well contain a genuine historical core. It is in keeping with the spirit of the gospels, presenting Jesus as compassionate and a healer of those in pain; furthermore, it presupposes his Jewishness, for it echoes the traditional Jewish precept that an animal fallen under his or her burden must be helped. Alluding to the Exodus, it tells us that God hears the cries not only of enslaved and suffering human beings, but also of beasts of burden, to whom most bystanders remain deaf--and takes action to deliver them.

Much more material could be gathered from other scriptural and apocryphal sources, including Islamic legends of Jesus and the long-lost Chinese "Jesus sutras" with their vegetarian Christianity (See Creatures of the Same God), but these must suffice for now.

No Single Picture

What can be learned from this survey?

It cannot be said that these varied accounts, from numerous sources over several centuries, offer an entirely consistent view of an attitude toward animals. Like the Hebrew scriptures / Old Testament, the Christian scriptures / New Testament and related sources do not present a totally God-suffused view of life, but rather portray life at least partly as we see it in this world, with all its confusion and ambiguity. Yet at the same time it is capable of receiving and bearing the grace of God -- even though the full import of grace received and borne within one may not always be understood.

Theologians such as Andrew Linzey who are concerned with animals rightly affirm, in my view, two principles which get at the heart of the gospel message, even if they were not always full comprehended at the start. These are that there is hope beyond despair even as we hear the whole creation, animals included, groaning and praying in anticipation of the consummation of all things; and that gospel ethics starts from universal unconditioned love, including love for all those who groan and pray even if not with human tongue.

Echoes of those principles can be heard in the limited source material here presented. Coherent or not, what does emerge at first glance is a picture of animals, from fish to fowl, from sheep to donkeys and fish: though lowly, and valued mostly for their economic benefit in a traditional rural society, nonetheless they can be bearers of crucially important messages about God and the world, about hope and neglect--and, supremely, about the importance of "the least of these" to a compassionate Creator.

1. Andrew Linzey, Creatures of the Same God. New York: Lantern Books, 2009, pp. 64. A.J. Arberry, The Koran Interpreted. New York: Macmillan, 1955, p. 80.

2. Linzey, Creatures of the Same God, pp. 66-67.

3. Linzey, Creatures of the Same God, pp. 60-61; Laura Hobgood-Oster, The Friends We Keep. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2010, pp. 108-09.

Unset Gems

“Even in the worm that crawls in the earth there glows a divine spark. "--Isaac Bashevis Singer, 1902-1991

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

You are my sister

Even when I hardly know you

You are my brother

Even when I may not show you

You're in my family

In Christ you're kin to me

One Light in me and thee--

Shall we learn to be Friends? . . . .

--Ken Medema (alt)

News Notes

Teen Saves Chicken Friend

A brave high school student named Whitney Hillman sneaked out of her class with a chicken tucked under her arm in order to save his or her life when the students were required to kill the chickens they had raised as part of an Animal Science and Food Production class. (Parents had not been informed.) Whitney had always liked animals, but had never connected the killing process to the food on her plate. After she saved Chicklett, however, she couldn't eat chicken again. To read the full article see Teen Hero .

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

Quaker School Teaches Turkey Killing

At mostly vegetarian Arthur Morgan School in N. Carolina, a program was introduced in which students raised and killed turkeys to eat at Thanksgiving. It was voluntary, but most of the eligible students signed on. A great deal of controversy has resulted. See Turkeys .

Milestone for Indonesian Wild Life

Greenpeace announces an important interim victory in its global campaign to save the forest dwellers, both human and wild life, especially orangutans, in the Paradise Forest of Indonesia. This area is being decimated by palm oil planters. Thanks to widespread protest organized by Greenpeace, the huge Nestlé company, a major buyer of palm oil from this area, has released a broad forest-protection policy, committing the company to make sure that its products have no deforestation footprint. This promise is a big step toward Greenpeace's goal of ending deforestation in this area by 2015.

--Contributed by Robert Ellwood

A Glimpse of the Peaceable Kingdom

--Contributed by Virginia Iris Holmes

This photo is one of several showing a happy meeting between a human couple, their two dog friends, and a young deer. If any readers know who the photographer is, please let us know.

Letter: Peter Opa

Dear Peaceable Friends,

I'm a Christian vegan who cares deeply about animals. One of the criticisms leveled against us vegans and vegetarians, which I have heard repeatedly in the course of my animal rights activism, is this: Our compassion for animals is self-serving and hypocritical because we don't seem to care about human suffering. While I disagree with this kind of blanket assessment, I must admit that it is often found that people who love animals will spend any amount of money to care for a pet, but are very indifferent to human suffering.

I'm a Christian vegan who cares deeply about animals. One of the criticisms leveled against us vegans and vegetarians, which I have heard repeatedly in the course of my animal rights activism, is this: Our compassion for animals is self-serving and hypocritical because we don't seem to care about human suffering. While I disagree with this kind of blanket assessment, I must admit that it is often found that people who love animals will spend any amount of money to care for a pet, but are very indifferent to human suffering.

To win hearts and minds to our cause, I believe our compassion for animals should be extended to vulnerable people. Having the reputation of "mean-spirited, out-of-touch animal lovers" doesn't serve our movement very well. I'm writing a book about this subject and I would like to hear your opinion. Do you agree that as vegans / vegetarians, our compassion should also go to fellow human beings? If so, how should we divide our time and resources between human and animal needs?

Please send your answers to peteropa@rethinkafrica.org . (If you'd like your letter considered for inclusion in PT, cc to graciafay@gmail.com .)

Peter Opa, from Benin in west Africa, has been residing in California for the last sixteen years. His Pilgrimage story will appear in the January PT. His concern about poverty and suffering in his country led him to form the non-profit organization Rethink Africa. See RethinkAfrica.org and AjaraProjects.org .

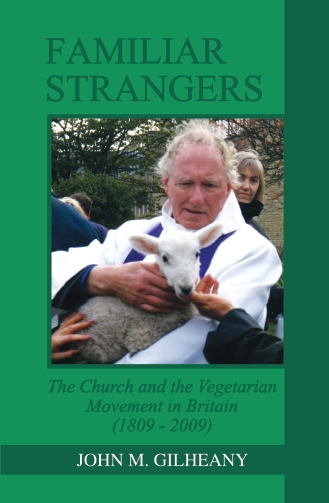

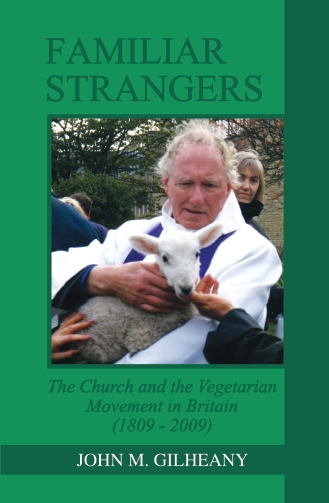

Book Review: Familiar Strangers

John M. Gilheany, Familiar Strangers: The Church and the Vegetarian Movement in Britain (1809 - 2009). Cardiff, Wales: Ascendant Press, 2010. Available in U.S. from Lulu Enterprises, Inc. www.lulu.com. 265 pages, $15.09.

This careful, well-documented chronology will be of immense benefit to all future researchers in this field. The narrative begins with the founding of the Bible Christian Church, an offshoot of the Swedenborgian "New Church," by the Rev. William Cowherd, formerly an Anglican priest and Swedenborgian minister. Unlike the mainline New Church, the Bible Christians -- following what seems to have been Emanuel Swedenborg's personal practice rather than formal doctrine -- insisted on vegetarianism, holding that flesh-eating was a result of the fall of humanity and therefore incongruous for those who professed to share in redemption and the resurrection life. It was Cowherd's successor as minister of the Bible Christian church in Salgate, Joseph Brotherton, who presided at a meeting in Ramsgate organizing the Vegetarian Society in 1847. Brotherton was also a reforming Member of Parliament who actively opposed child labor and evil factory conditions.

This careful, well-documented chronology will be of immense benefit to all future researchers in this field. The narrative begins with the founding of the Bible Christian Church, an offshoot of the Swedenborgian "New Church," by the Rev. William Cowherd, formerly an Anglican priest and Swedenborgian minister. Unlike the mainline New Church, the Bible Christians -- following what seems to have been Emanuel Swedenborg's personal practice rather than formal doctrine -- insisted on vegetarianism, holding that flesh-eating was a result of the fall of humanity and therefore incongruous for those who professed to share in redemption and the resurrection life. It was Cowherd's successor as minister of the Bible Christian church in Salgate, Joseph Brotherton, who presided at a meeting in Ramsgate organizing the Vegetarian Society in 1847. Brotherton was also a reforming Member of Parliament who actively opposed child labor and evil factory conditions.

Though Gilheany's tale opens with the 1847 event, he gives due attention to Cowherd and Brotherton's eighteenth-century predecessors in vegetarian concerns, such as the Anglican priest Humphrey Primatt and John and Charles Wesley of Methodism. The story continues after 1847 with the fairly well known London Vegetarian Society in the days when Mohandas K. Gandhi (as a young student from India) and Josiah Oldfield were among its officers.

This book is generally well-balanced, though one or two chapters devoted to otherwise obscure clergymen may seem disproportionate. So also might a chapter dedicated to the dismal waverings of Ralph Inge, the "Gloomy Dean" of St. Paul's Cathedral. The "debate" between George Bernard Shaw and G.K. Chesterton on vegetarianism, sporadic as it was, perhaps was not as influential as the attention given it here would suggest. But the summary of that confrontation, with quotes, is well worth reading nonetheless.

Here we listen in on a battle of wits between two of the wittiest writers of the century. Chesterton, provocatively exuberant defender of Christian orthodoxy as he understood it, first as an Anglican then Roman Catholic, is one writer I enjoy reading even when I disagree with him, as I often do, simply for his never-dull style, his paradoxical arguments, and his tremendous enthusiasm for words and ideas. That lay apologist's basic point regarding vegetarianism seems to have been that Christians ought to follow the Pauline model of cultural accommodation and concern for the weaker brethren in such non-essentials as diet, the better to work for Christ in and through the culture with festive joy, rather than coming across as priggish. Shaw was more concerned with final values. For the great playwright, vegetarianism was better for the health of the planet, the animals, and himself. The svelte Shaw may have finally won the argument by living to be 94 as over against the grossly obese Chesterton's 62; Shaw liked to say he had outlived all the doctors who told him he could never survive on a vegetarian diet.

Another unforgettable figure, of a few years later, was Air Marshall Lord Dowding, head of the Royal Air Force Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain. Dowding's masterly deployment of very limited personnel and plane resources saved the island kingdom during its darkest, and finest, hour; it was of his pilots that Churchill said, "Never . . . was so much owed by so many to so few." Dowding was also a firm vegetarian, who after the war gave more than fifty speeches in the House of Lords on behalf of vegetarianism and animal welfare. His no less committed wife, Muriel, Lady Dowding, founded the still-active firm Beauty Without Cruelty, an enterprise dedicated to cosmetic products free of animal ingredients or testing.

Other chapters present various colorful Victorian and later organizations which have promoted vegetarian ideals, such as the Order of Danielites, the Order of the Cross, the Order of the Golden Age, the International League of St. Hubert, the Guild of St. Francis. As the names suggest, most were loosely Anglican, sometimes combining theatrical rituals with mystical teaching in the spirit of the "Christian Mysteries" perspective popular in the Church of England around the turn of the twentieth century. But groups like these had their rise and fall, while more prosaic but more firmly denominationally-based bodies, such as the Anglican Society for the Welfare of Animals, Catholic Concern for Animals, Quaker Concern for Animals, Friends Vegetarian Society, and the Methodist Animal Welfare Group, if not all strictly vegetarian, have done much to raise awareness and have showed staying power and some growth in the later decades of the twentieth and the early twenty-first centuries. Friends may be particularly interested in a quote from George Fox here given: [The Lord desires] "not that you should spend the creatures upon your lusts, but to do good with them. . . for nothing brought you into the world, nor nothing you shall take out of the word, but leave all creatures behind you as you found them." (p. 147)

Final chapters present a mixed but generally encouraging picture of the vegetarian movement in Britain today. As one might expect, the nation is still of two minds on the subject of animals for food: it is the land of the hearty roast beef of old England and the "full English breakfast" involving bacon and kippers, and at the same time the home of passionate animal lovers and countless humane societies. In such a country Chesterton could earlier write with terrible vividness of the searing death of a small feathered creature from a high-speed metal projectile sent on its way by an English gentleman, who considers what he is doing "sport," --then go on to point out that the hunter is not really a bad sort, given his social environment, and that outright condemnation of him would not only be bearing false witness, but would do no good.

Likewise, the verbiage emanating from British church assemblies and leaders in recent decades has tended to wobble awkwardly between regard for the public's increasing awareness of animal abuse, and concern for the church's rural base and economic necessities. Understandably, many Christians with serious animal concerns have put their main energies into separate organizations like those just named. Nonetheless, all the evidence points to a gradual but discernible growth in animal concern and in vegetarianism in Britain, as in other comparable countries, at the present time. More and more vegetarian food on market shelves, more restaurants, more publications, more groups and meetings, more celebrities embracing the cause, meet the eye and bespangle the media as the twenty-first century advances.

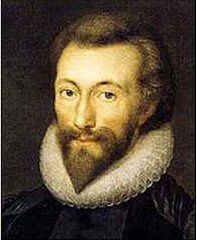

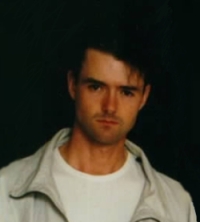

Readers of all nations with serious vegetarian concerns should read this important volume. Not only was Britain the home of some of the earliest and most influential pro-animal activity in the modern West, but the rhetoric here presented well sums up many of the major issues. Furthermore, by giving special attention -- as not all such histories do -- to the relationship of vegetarianism and the Christian church, a valuable perspective is offered. Some have given up too easily on vegetarianism and Christianity, as though that faith were the enemy. John Gilheany (pictured) shows that it also has been, and can still be, an ally. Read this book and find out when, how, and why.

Readers of all nations with serious vegetarian concerns should read this important volume. Not only was Britain the home of some of the earliest and most influential pro-animal activity in the modern West, but the rhetoric here presented well sums up many of the major issues. Furthermore, by giving special attention -- as not all such histories do -- to the relationship of vegetarianism and the Christian church, a valuable perspective is offered. Some have given up too easily on vegetarianism and Christianity, as though that faith were the enemy. John Gilheany (pictured) shows that it also has been, and can still be, an ally. Read this book and find out when, how, and why.

--Robert Ellwood

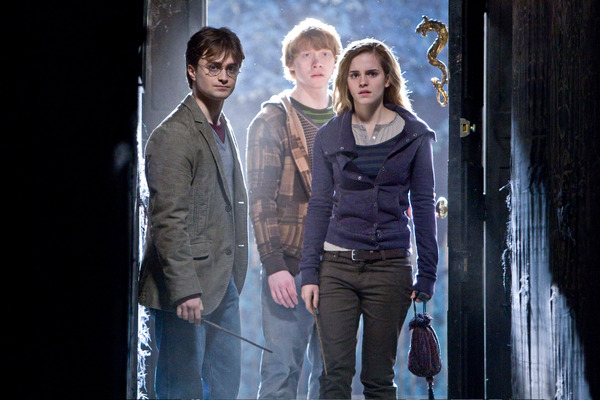

Film Review: Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part I

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part One. A Warner Brothers Film, based on the novel by J. K. Rowling, directed by David Yates. Starring Emma Watson as Hermione Granger, Daniel Radcliffe as Harry Potter, Rupert Grint as Ron Weasley, Helena Bonham Carter as Bellatrix Lestrange. Rated PG-13. 2011.

In this, the seventh Harry Potter film, based on the first half of the seventh novel of the series, Harry is on the run. He must flee from his unhappy but safe home before he turns seventeen and is captured or killed by the forces of evil, who have taken over the Ministry of Magic and Hogwarts. He tries to go off by himself, but his best friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger insist on sharing his hardships in the search for the Horcruxes, the seven magical objects in which the One who must not be named has hidden pieces of his soul.

In this, the seventh Harry Potter film, based on the first half of the seventh novel of the series, Harry is on the run. He must flee from his unhappy but safe home before he turns seventeen and is captured or killed by the forces of evil, who have taken over the Ministry of Magic and Hogwarts. He tries to go off by himself, but his best friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger insist on sharing his hardships in the search for the Horcruxes, the seven magical objects in which the One who must not be named has hidden pieces of his soul.

Amidst great danger and suffering, the three young heroes manage to find and retrieve one Horcrux, and then to destroy it after even greater danger and more suffering. To complicate matters even further, they learn of the existence of the three Deathly Hallows: an invincible magic wand, a stone that can bring back the dead (not necessarily a good thing!), and a cloak of invisibility. In this movie, we learn of the fate of only the first of these - the wand, which falls into the hands of the great enemy.

The atmosphere throughout is one of dread and gloom. The world of witches and wizards, as it increasingly succumbs to the power of the enemy, becomes something very much like the Third Reich and the world of Orwell's 1984. Those suspected of "racial impurity" are cruelly persecuted; suspicion and betrayal are the order of the day.

The film is a very close and faithful adaptation of the novel. There are are a couple of scenes omitted which I would have preferred to see: Harry and his cousin Dudley becoming reconciled at long last (after 16 years); Hermione persuading Harry to treat Kreacher (called an "Elf," but he looks more like a hobgoblin to me) with kindness--which works like a charm.

There is a scene that is in the film but not in the book: Before making his escape from Privet Drive, Harry sets Hedwig - his beloved messenger owl - free. Perhaps he is thinking something like the

famous saying: "If you love someone, set them free. If they love you, they will come back. If not, they were never really yours." Maybe not. Maybe Harry is worried that Hedwig would be harmed, and he is setting her free to ensure her life and safety. Alas, using her magic abilities to find whomever she seeks, Hedwig reappears and intercepts Harry's flight, and catches a death-bolt meant for Harry. So her death is not prevented, but it is at least ennobled. Instead of dying as a helpless victim in a cage, Hedwig dies a hero, defending the human she loves. I cried. This is about the only animal reference, but it speaks well for all feathered beings.

Her death is one of seven in the film. One is a happy death of ripe old age, one is a suicide, five are horrible murders (though quick and painless). In addition to the deaths, there is a plethora of fear, torture, and violence. Of course, to some people those would be selling points rather than deal-breakers, so I can recommend the movie to them without hesitation. I also recommend it to those of us who love Hermione, Harry and Ron. If you are in this group, of course you must see this movie. But you already know that, and wild unicorns could not keep you away.

-Benjamin Urrutia

Recipes

Oatmeal-Coconut Cookies

Makes about 18 - 24 cookies

1 stick Earth Balance

1 stick Earth Balance

½ cup light brown sugar

2 T. agave nectar

1 cup quick cooking oats

¾ cup unbleached flour

¼ cup shredded or grated coconut (unsweetened)

¼ tsp. sea salt

1 tsp. baking soda

Preheat oven 325° F. Line two baking sheets with parchment paper.

In small saucepan, place Earth Balance, brown sugar, and agave nectar over medium- low heat. Melt Earth Balance and dissolve brown sugar.

In a medium sized bowl, stir together oats, flour, coconut, and sea salt. Stir in melted Earth Balance mixture.

In a small bowl or cup combine 1 tsp. soda with 1 tsp. warm water, then stir into oat mixture. When dough is cool enough to handle, scoop tablespoonfuls of dough to form small balls. Place on the baking sheet at least 2 inches apart. Lightly press each ball to very slightly flatten.

Bake 10 - 12 minutes until golden. Remove from baking sheet and cool on racks. Serve with afternoon tea or coffee.

-- Angela Suarez

Curried Butternut Squash Soup

serves 6

1 yellow onion, finely chopped

2 T. extra virgin olive oil

1 medium-large butternut squash

8 cup vegetable broth

2 tsp. curry powder, or to taste

sea salt, to taste

freshly ground black pepper, to taste

In a large saucepan sauté onion in olive oil until translucent. Add butternut squash along with ½ cup spring water and curry powder; cook until squash is tender. Place butternut squash and onion in the bowl of a food processor and process until puréed. This may need to be done in 2 or more batches, depending on size of food processor bowl. Return butternut squash purée to saucepan; add vegetable broth. All 8 cups may not be needed. Allow the soup to remain fairly thick. Season to taste with sea salt and freshly ground black pepper.

Cook on low heat until evenly heated and hot. Ladle into bowls, and serve immediately.

-- Angela Suarez

Quick and Easy Christmas Fudge

Makes about 16 pieces

1/2 cup Earth Balance "butter," plus a little extra

1/2 cup Earth Balance "butter," plus a little extra

1/2 cup soymilk

1 12-oz package Fair Trade semi-sweet chocolate chips

4 cups powdered sugar

1 teas. vanilla

1/2 cup chopped walnuts, or dried fruit such as currants or cherries (optional)

"Butter" an 8-inch square pan with small amount of Earth Balance. Combine rest of Earth Balance, soymilk, and chocolate chips in large saucepan, preferably non-stick. Cook and stir over low heat until melted. Stir in powdered sugar; add vanilla; beat with hand-held mixer at medium speed until smooth. Remove from heat; stir in walnuts or dried fruit if desired. Spread in 8-inch pan, cover, and refrigerate until firm, about 2 hours.

This fudge is a little creamier than the traditional kind, much easier to make, and tastes just as good. Because of the slightly softer texture, you may want to wrap the pieces individually if they are to be served to guests.

--GFE

My Pilgrimage: Franceen Neufeld

A Crack in the World

It is like there is a crack in the world, and I am in danger of falling through. Over the past few years, the crack has opened wider and wider, and new fissures have spread out from it, until in every direction there it stretches to my visible horizon.

The crack is the pain of everything around me. I who feel the pain of others, don't know what to do, don't know how to stop it happening, don't know how to avoid falling in at every turn. And so I have tried standing still and hiding but I can't find myself that way. So now I try to find words for my silence, and for the screaming going on all around me.

Why must we hurt anything--everything?--merely to satisfy our hunger? Is our craving that imperative? Our senses so dull that all we feel is what goes on in our own small truth? What if we let in the truth of others? Of you the "other" whose life is in our hands.

And so I make my eyes lock with your eyes, and the vulnerability there is like a knife to my soul. How can we steal from you? Rip away from you everything that matters to you? Who told us we could do that?

And for those who do that, are there any words that would make a difference?

I used to be able to do that. Not in person, but through an agent, someone who did the processing. And then one day the intermediary fiction dropped away as I sat in a car behind a truck, the back door open and your bodies--things stripped of you--hanging there in all the horrible truth that was yours to endure at my hands. My hands, though I had ceded the guilt to others for so long. Now it was my guilt and I looked it straight in its blood and bones and sinews, and the rest of my life would be a sorrow for it.

And so the crack in your world became the crack in mine, and I walk down grocery aisles with tears coursing through my veins. And I desperately shield my mind from monstrous stories that begin with playful babies who don't know how few weeks they have before their torture begins. The thirst, the heat, the cold, the starvation, the fear. And you, helpless against violence, still a screaming baby, billions of screaming babies. Someone's baby, ripped from her side to be stripped of life to feed the stomachs of others who don't even care what was stolen from you.

So how does this story ever end? How do I go on with the blood of innocents pulsing through my consciousness in every meal I share with meat-eaters across from me? With the screams hollowing out my conscience every time I avert my eyes rather than speak of my grief for you.

Billions and billions. And me, with nothing for your agony but my tears.

I'm sorry.

Franceen Neufeld lives near Kingston, Ontario (Canada) with her husband Ron and their two great-hearted Leonberger dogs, Kazan and Beowulf. Franceen and Ron have four grown children and six grandchildren. Franceen's interests include theology, writing, and caring for others.

Poetry: John Donne, 1572 - 1631

Sonnet XII

Why are wee by all creatures waited on?

Why are wee by all creatures waited on?

Why doe the prodigall elements supply

Life and food to mee, being more pure than I,

Simple, and further from corruption?

Why brook'st thou, ignorant horse, subjection?

Why dost thou bull, and bo[ar] so seelily*

Dissemble weaknesse, and by one mans stroke die,

Whose whole kinde, you might swallow and feed upon?

Weaker I am, woe is mee, and worse than you,

You have not sinn'd, nor need be timorous.

But wonder at a greater wonder, for to us

Created nature doth these things subdue,

But their Creator, whom sin, nor nature tyed,

For us, his Creatures, and his foes, hath dyed.

*Seely/silly: weak, defenseless (archaic)

Opinions of some of the staff are divided about this poem. One interpretation is that the line beginning "Created Nature" legitimizes the human enterprise of enslaving and eating animals. The other view is that, whatever the literal assertion of that line, the tone of the first ten lines strongly condemns our treatment of animals, while the last two proclaim a marvelous transcending of the present state of affairs.

What does thee think, Friend?

The Peaceable Table is

a project of Quaker Animal Kinship / Animal Kinship Committee of Orange Grove Friends Meeting, Pasadena, California. It is intended to resume the witness of that excellent vehicle of the Friends

Vegetarian Society of North America, The Friendly

Vegetarian, which appeared quarterly between 1982 and

1995. Following its example, and sometimes borrowing from its

treasures, we publish articles for toe-in-the-water

vegetarians as well as long-term ones.

The journal is intended to be

interactive; contributions, including illustrations, are

invited for the next issue. Deadline for the January issue

will be Dec 27, 2010. Send to graciafay@gmail.com

or 10 Krotona Hill, Ojai, CA 93023. We operate primarily

online in order to conserve trees and labor, but hard copy

is available for interested persons who are not online.

The latter are asked, if their funds permit, to donate $12 (USD) per year. Other

donations to offset the cost of the domain name and server are welcome.

Website: www.vegetarianfriends.net

Editor: Gracia Fay Ellwood

Book and Film Reviewers: Benjamin Urrutia & Robert Ellwood

Recipe Editor: Angela Suarez

NewsNotes Editors: Lorena Mucke and Marian Hussenbux

Technical Architect: Richard Scott Lancelot Ellwood

I'm a Christian vegan who cares deeply about animals. One of the criticisms leveled against us vegans and vegetarians, which I have heard repeatedly in the course of my animal rights activism, is this: Our compassion for animals is self-serving and hypocritical because we don't seem to care about human suffering. While I disagree with this kind of blanket assessment, I must admit that it is often found that people who love animals will spend any amount of money to care for a pet, but are very indifferent to human suffering.

I'm a Christian vegan who cares deeply about animals. One of the criticisms leveled against us vegans and vegetarians, which I have heard repeatedly in the course of my animal rights activism, is this: Our compassion for animals is self-serving and hypocritical because we don't seem to care about human suffering. While I disagree with this kind of blanket assessment, I must admit that it is often found that people who love animals will spend any amount of money to care for a pet, but are very indifferent to human suffering.  This careful, well-documented chronology will be of immense benefit to all future researchers in this field. The narrative begins with the founding of the Bible Christian Church, an offshoot of the Swedenborgian "New Church," by the Rev. William Cowherd, formerly an Anglican priest and Swedenborgian minister. Unlike the mainline New Church, the Bible Christians -- following what seems to have been Emanuel Swedenborg's personal practice rather than formal doctrine -- insisted on vegetarianism, holding that flesh-eating was a result of the fall of humanity and therefore incongruous for those who professed to share in redemption and the resurrection life. It was Cowherd's successor as minister of the Bible Christian church in Salgate, Joseph Brotherton, who presided at a meeting in Ramsgate organizing the Vegetarian Society in 1847. Brotherton was also a reforming Member of Parliament who actively opposed child labor and evil factory conditions.

This careful, well-documented chronology will be of immense benefit to all future researchers in this field. The narrative begins with the founding of the Bible Christian Church, an offshoot of the Swedenborgian "New Church," by the Rev. William Cowherd, formerly an Anglican priest and Swedenborgian minister. Unlike the mainline New Church, the Bible Christians -- following what seems to have been Emanuel Swedenborg's personal practice rather than formal doctrine -- insisted on vegetarianism, holding that flesh-eating was a result of the fall of humanity and therefore incongruous for those who professed to share in redemption and the resurrection life. It was Cowherd's successor as minister of the Bible Christian church in Salgate, Joseph Brotherton, who presided at a meeting in Ramsgate organizing the Vegetarian Society in 1847. Brotherton was also a reforming Member of Parliament who actively opposed child labor and evil factory conditions. Readers of all nations with serious vegetarian concerns should read this important volume. Not only was Britain the home of some of the earliest and most influential pro-animal activity in the modern West, but the rhetoric here presented well sums up many of the major issues. Furthermore, by giving special attention -- as not all such histories do -- to the relationship of vegetarianism and the Christian church, a valuable perspective is offered. Some have given up too easily on vegetarianism and Christianity, as though that faith were the enemy. John Gilheany (pictured) shows that it also has been, and can still be, an ally. Read this book and find out when, how, and why.

Readers of all nations with serious vegetarian concerns should read this important volume. Not only was Britain the home of some of the earliest and most influential pro-animal activity in the modern West, but the rhetoric here presented well sums up many of the major issues. Furthermore, by giving special attention -- as not all such histories do -- to the relationship of vegetarianism and the Christian church, a valuable perspective is offered. Some have given up too easily on vegetarianism and Christianity, as though that faith were the enemy. John Gilheany (pictured) shows that it also has been, and can still be, an ally. Read this book and find out when, how, and why. In this, the seventh Harry Potter film, based on the first half of the seventh novel of the series, Harry is on the run. He must flee from his unhappy but safe home before he turns seventeen and is captured or killed by the forces of evil, who have taken over the Ministry of Magic and Hogwarts. He tries to go off by himself, but his best friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger insist on sharing his hardships in the search for the Horcruxes, the seven magical objects in which the One who must not be named has hidden pieces of his soul.

In this, the seventh Harry Potter film, based on the first half of the seventh novel of the series, Harry is on the run. He must flee from his unhappy but safe home before he turns seventeen and is captured or killed by the forces of evil, who have taken over the Ministry of Magic and Hogwarts. He tries to go off by himself, but his best friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger insist on sharing his hardships in the search for the Horcruxes, the seven magical objects in which the One who must not be named has hidden pieces of his soul.

1 stick Earth Balance

1 stick Earth Balance 1/2 cup Earth Balance "butter," plus a little extra

1/2 cup Earth Balance "butter," plus a little extra

Why are wee by all creatures waited on?

Why are wee by all creatures waited on?