Editorial: The Inner Light and the Honor Code

The Mansfield Judgment

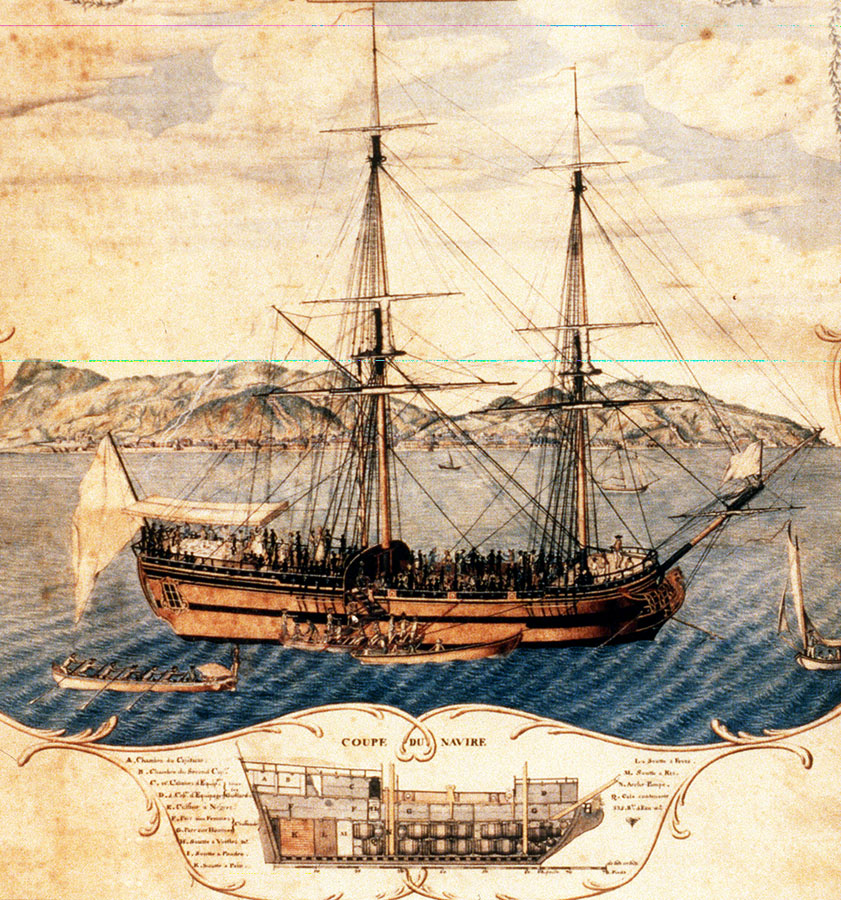

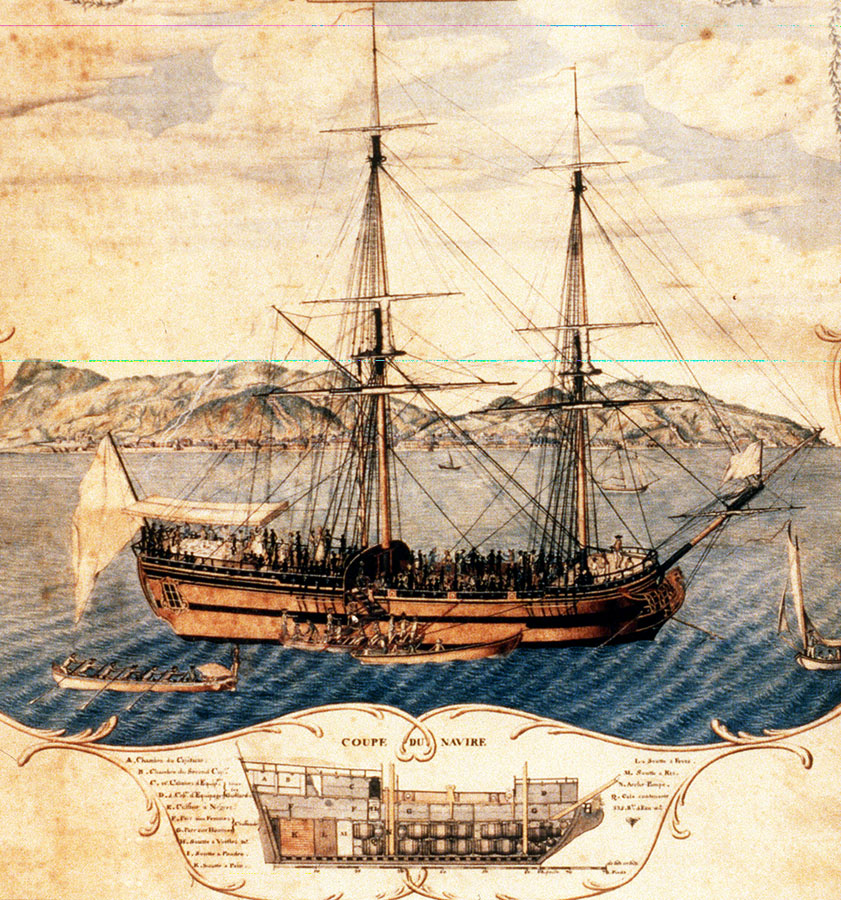

In 1769 a customs official named Charles Steuart, from the British colony of Massachusetts, took with him to England one James Somersett, an enslaved African he had purchased in Virginia. Steuart was not pleased when Somersett escaped in 1771. He recaptured his "property" that November, and put him in chains aboard the ship Ann and Mary, bound for the colony of Jamaica, where Steuart intended to sell him. But Somersett's godparents, Mary Cade, Thomas Marlow, and John Walkin, asked the Court of the King's Bench for a ruling of habeas corpus, claiming that their godson's re-enslavement was not legal.

The case attracted much attention in the press, and by the time of the hearings, Somersett had no fewer than five legal counsel. One of them argued in effect that slavery is incompatible with what it means to be English, entailing that when Somersett set foot in England he became a free man. After weeks of deliberation the judge, William Murray, earl of Mansfield, gave his decision in the ex-slave's favor. Although Mansfield based his decision on legal technicalities, he made it clear that slavery was "odious" and could only be maintained under "positive law" supporting it, which did not exist in England. This so-called Mansfield Judgment was to be influential in the campaigns, over the next sixty years, to abolish the British institutions of kidnapping and holding African humans in chattel slavery.

The case attracted much attention in the press, and by the time of the hearings, Somersett had no fewer than five legal counsel. One of them argued in effect that slavery is incompatible with what it means to be English, entailing that when Somersett set foot in England he became a free man. After weeks of deliberation the judge, William Murray, earl of Mansfield, gave his decision in the ex-slave's favor. Although Mansfield based his decision on legal technicalities, he made it clear that slavery was "odious" and could only be maintained under "positive law" supporting it, which did not exist in England. This so-called Mansfield Judgment was to be influential in the campaigns, over the next sixty years, to abolish the British institutions of kidnapping and holding African humans in chattel slavery.

Introducing the Honor Code

Two important themes are discernible in this case: an awareness of atrocious injustice, and a sense that (national) honor requires a correcting of that injustice. The latter theme is the topic of a major book by philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen. Appiah, who grew up in Ghana, was educated in England and now teaches at Princeton, analyzes the part that conceptions of honor played in four revolutions of varying moral weight: the ending of the duel, the freeing of Chinese women's feet, the abolition of Atlantic slavery, and the contemporary campaigns against the "honor" murders of women in Pakistan and other middle-eastern countries. (He mentions factory farming, together with still other social evils, in passing, suggesting that issues of honor may have a part in ending it as well.)

Despite having prevailed for hundreds of years (footbinding for nearly a thousand), the first three of these evils each fell within about a generation. The moral objections to them were already known, says Appiah; the main thing that was different was the conception of honor.

Appiah's analysis of honor shows it to be complex; the word applies not only to the respect shown to those in the upper ranks of a hierarchy just because of the class in which they were born, but also the esteem granted those who meet or exceed the standards of their class or category. This dual meaning implies that a person can both be honorable and be shamed at the same time for closely linked reasons. (An example might be Mr. Darcy of Pride and Prejudice, who is proud of his status as a gentleman of wealth and aristocratic lineage, but also deeply ashamed because, as Elizabeth Bennet tells him, his behavior has been arrogant and disdainful, and thus not gentlemanlike.) A form of honor--dignity--can be claimed by all human beings, including those of low class or poor achievement.

From Honor to Shame

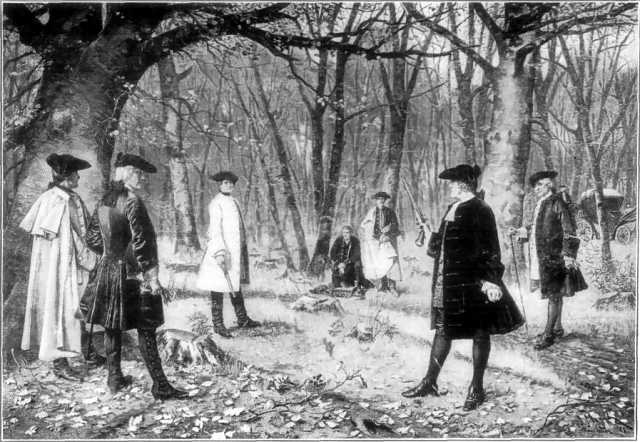

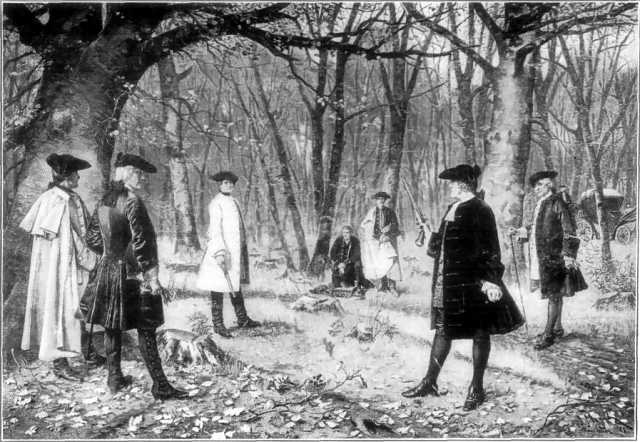

Different but linked aspects of honor stand out in the three successful revolutions. The duel was an institution in which aristocrats defended their honor against the perceived insults of others of their class, thereby flaunting both their (supposed) manliness and their ability to get by with a crime punishable by death among the lower orders. But the duel's days were numbered when social and political power began to shift from the hereditary aristocrats to the middle class. When bankers, or--even worse--linendrapers' assistants took to dueling, the institution began to seem ridiculous, and fizzled out. Thus what the condemnation of its irrationality and deadly violence and could not achieve was brought about by laughter.

Similarly, for centuries Chinese footbinding was associated with upper-class status; despite occasional protests against its cruelty, it was so crucial to social acceptability that without it a woman was not thought to be marriageable. Becoming more and more widely adopted did not make it seem ridiculous, perhaps because in essence it served not to assert a man's power, but to imply a woman's disempowerment: a woman with tiny, deformed feet literally could not go her own way. What caused it to fall was not an internal shift of power so much as a broadening, so to speak, of the cultural conversation. During the mid-nineteenth century, China's proud sovereignty was breached by the West, and forced to accept humiliating trade arrangements. Western ideas also entered more quietly, through resident Westerners, especially missionaries--both women and men being particularly influential in condemning footbinding--and young Chinese men who returned from studying in universities like Cambridge or Harvard. Finding that Westerners considered bound feet grotesque, those who cared about their country increasingly felt that the "golden lotuses" were not a woman's pride but China's shame. In such an atmosphere the institution could not long survive.

Appiah makes a case that honor was also involved in the movement to end British involvement in slavery. William Wilberforce, the devout Evangelical statesman who led the campaigns in Parliament for decades, pointed out that slavery was incompatible with Britain's claim to be Christian, and was thus a blot upon its honor. For an individual to be preoccupied with his own honor was selfish, unworthy; but concern for national honor could enable one to get beyond himself and sacrifice for the greater good, thus wielding moral power. Furthermore, group honor as basic human dignity was a particular issue in the involvement of the working classes in the anti-slavery movement. Many voices compared the abuses and exploitation workers suffered with those undergone by slaves. A sense of identification took root: like the slaves, workers were mistreated and held in contempt because they labored. But workers increasingly came to hold that labor deserves respect. Workers in northern manufacturing cities competed with one another by city to gain the greatest number of signatures on petitions to Parliament and pledges to boycott West Indian sugar. And Parliament began to accept the idea that they had to listen to the "lowly" instead of only talking down to them.

Regarding Appiah's insightful discussion of present-day campaigns against the "honor" murders of women in Pakistan and other countries, it is noteworthy that, as with the anti-slavery campaigns, activists claim their nation's religion as ally, so that the widespread flouting of its principles is a source of shame. There is broad (if not entirely unanimous) agreement, in Pakistan and elsewhere, that honor murders are incompatible with Islam, one of whose central assertions is "Allah is compassionate." Another similarity is a broadening of cultural conversation, facilitated by the Internet, leading to an alliance between the victimized class and women in other countries. As British workers identified with abused slaves, foreign women today see their own dignity being assaulted by the evil practice.

Basic Dignity and the Light

When honor (as catalyst for change) is understood as the basic dignity of all persons, we are not far from the central Quaker conviction that there is an Inner Light, or That of God, in everyone. Of course, universal dignity may also have somewhat different bases, e.g. the Jewish and Christian belief that all persons are created in the image of God, or the conviction of our country's founding fathers of a self-evident truth that all men [sic] are created equal. But let us briefly pursue the implications of the Light as the source of a changed conception of honor that may hasten the moral revolution that we seek.

Early Friends were in fact much concerned with the meaning of honor. They lived in a society polarized by class, in which people of lower classes (as were most of them) were expected to bow and doff their hats to richly-dressed aristocrats, addressing them by title. But on the basis of their

experience of the Divine Light as one in all persons and conferring true honor on all, Quakers rejected such practices, keeping their hats on, using only the title "Friend" (derived from John 15:15, "No longer do I call you servants . . . but I have called you friends"). This rejection of titles essentially continues today. The presence in every person of the equalizing and unifying Light was, and is, also the basis for Friends' refusal of exploitation, war, and other forms of violence. In the last few decades Friends have increasingly come to affirm the presence of the Light throughout the cosmos, and many other spiritually aware people as well are affirming that human treatment of nature must change radically. But for most, this expanded vision has obviously not yet materialized into a stance of nonviolence toward animals.

Honor and the Revolution for Animals

Readers of PT may not all think in terms of the Divine Light present in every heart, but most probably agree that both animals and people are due the respect, or even reverence, that would be appropriate for those in whom the Light dwells. How might this conviction help us communicate better with the unconvinced?

The way the duel ended--by being shown as embarrassing and ridiculous--is not the way for us to take. Many meat-eaters already see vegetarians as looking down on them from their moral high ground and holding them in contempt, or accusing them of dark deeds. In fact they are born into a system that does make them complicit in terrible cruelties to animals, whether knowingly or not; and informing them of these unwelcome facts is a necessary part of our message. But it must be presented in ways that will awaken their compassion. Trying to shame them for their complicity would in most cases make them more defensive.

It is more profitable to stress the positive sides. The general view justifying the status quo--that a "food" animal is a dimwitted, lumpish object, identical to every one of "its" kind--must be corrected by information supporting animals' basic dignity. Such information is increasingly available thanks to ethologists and other observers: animals are complex and sensitive beings, capable both of pleasure and of terrible suffering; many are capable of love.

It is also good to stress the basic dignity of the human beings we are addressing. They are bearers of the Light, or of the Divine Image; they have the potential for manifesting gleams of the divine love to "the least of these." A certain percentage of people do evil with no apparent compunctions, but a great many intend to be decent, caring folk. In their innermost being, probably unknown even to themselves, all are far better than what they do with their forks in support of the evil system that entraps them. With the help of the Spirit of God, they can become free from that system, so that their actions more and more show who they really are.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

Illustrations: The slave ship Marie Seraphique; William Murray, earl of Mansfield; The duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr; Early Quaker Meeting.

Unset Gems

"We have a duty to know."

--Dorothee Soelle, 1929-2003, theologian and social activist

"The air of England is too pure for a slave to breathe."

--Counsel for James Somersett before Justice Mansfield, 1772

"How is it possible for you to have faith while you take honour one from another and have no desire for the honour which comes from God only?"--John 5:44

A Word of Thanks

The members of Quaker Animal Kinship, sponsor of The Peaceable Table, want to express our thanks to those who responded to our appeal for funds. We especially want to thank Ms. Claire Williams, age seven, who donated more than $11.50 out of her allowance to help our animal friends. Friend Claire 's compasion and generosity are an inspiration to us all.

The members of Quaker Animal Kinship, sponsor of The Peaceable Table, want to express our thanks to those who responded to our appeal for funds. We especially want to thank Ms. Claire Williams, age seven, who donated more than $11.50 out of her allowance to help our animal friends. Friend Claire 's compasion and generosity are an inspiration to us all.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

For Quaker Animal Kinship

NewsNotes

Do Animals Have Spiritual Experiences?

Studies by neurologist Kevin Nelson of the University of Kentucky indicate that because animals share with us humans the primitive brain areas linked to out-of-body, mystical, and other spiritual experiences, in all likelihood they have such experiences also. Ethologists Marc Bekoff and Jane Goodall support the idea that they (probably) do, citing incidents in which animals show signs of awe before scenes of tremendous grandeur. (Nelson claims that the brain areas in question originate the experiences, which is not necessarily the case.; these areas could instead be receptors of that which transcends us.) See Spiritual Experience.

Studies by neurologist Kevin Nelson of the University of Kentucky indicate that because animals share with us humans the primitive brain areas linked to out-of-body, mystical, and other spiritual experiences, in all likelihood they have such experiences also. Ethologists Marc Bekoff and Jane Goodall support the idea that they (probably) do, citing incidents in which animals show signs of awe before scenes of tremendous grandeur. (Nelson claims that the brain areas in question originate the experiences, which is not necessarily the case.; these areas could instead be receptors of that which transcends us.) See Spiritual Experience.

--Contributed by Deborah Elliott

Wild Chimpanzees Play with "Dolls"

A new report in Current Biology shows that chimpanzees in Uganda, eastern Africa, especially young females, may use sticks as dolls, carrying them around, embracing them, and even putting them to bed. These findings by researcher Sonya Kahlenberg and her co-author shed new light on the ability of chimps to imagine inanimate objects as living. See Chimps and Dolls

My Pilgrimage: Peter Opa

Veganism: An African's Journey

My decision to become a vegan was informed by several different and interrelated reasons: concern for animals, care for the earth, compassion for the poor, and good health.

My decision to become a vegan was informed by several different and interrelated reasons: concern for animals, care for the earth, compassion for the poor, and good health.

I come from a little village in West Africa called Ajara, located near the border between the Benin Republic and Nigeria. My tribe, known as Gu, or Fon, is from the Benin Republic. Growing up on the farm, I was sheltered from the technologies of civilization. There were no televisions, no telephones. Everybody played and ate together. Everything was in its natural state and very green. Pristine rivers, beautiful coconut trees, mango trees, cashew trees in rich farm lands were everywhere around us, graced with colorful birds, butterflies, and all kinds of animal species. Rain was regular and sufficient. Harvests were rich, food abundant, nature's cycles untroubled. We breathed pure, clean air and ate locally grown food. To the grazing animals, the earth was kind. The thick, green forest was dense with medicinal plants.

But as a child, I was uncomfortable with meat, something very rare for an African. I did not have any health issues whatsoever, but I felt incredibly sensitive to blood. As a result, unlike other children, I had a weird feeling about eating meat. My discomfort also had to do with how brutally animals were killed for food and rituals. Not knowing of any alternative way, I kept forcing myself to eat it.

But as a child, I was uncomfortable with meat, something very rare for an African. I did not have any health issues whatsoever, but I felt incredibly sensitive to blood. As a result, unlike other children, I had a weird feeling about eating meat. My discomfort also had to do with how brutally animals were killed for food and rituals. Not knowing of any alternative way, I kept forcing myself to eat it.

In 1990 my educational dream took me to Obafemi Awolowo University, about five hundred miles from my village. Shortly after graduation, I moved to Europe, and finally to the United States. Though I have always felt compassionate toward animals, it wasn’t until I came to the United State that I found out about the vegan/vegetarian movement. I was happy to discover there are active groups of people who share my compassionate worldview and feelings about animals, which are rare in Africa.

Apart from concern for animals, there is another compelling reason for me not to eat meat in America: health. Though not a good choice, eating meat in Africa is safer because the animals are naturally fed without any growth hormones or chemicals. But most meat in America is laden with these artificial substances, leading to widespread cancer, premature development in kids, and all kinds of degenerative diseases.

So, the decision was made: No more meat for me. But my compassion didn’t want to stop there. As I got comfortable in America, I began to think deeply about the people I left behind. In 2007 I had the joy and excitement of visiting my village with my girlfriend, Val, after being away for so many years. But was not the the pristine environment I grew up in. Some of the rivers had either receded or completely dried up. The swampy areas, home to huge snails, had turned into parched ground. Medicinal herbs were fast disappearing and the native doctors (herbalists) were deeply troubled. Wells were drying up and women had to seek harder for water. Farmers were worried and frustrated by the vagaries in the weather.

I recall with tears what my childhood friend, Zossou, told me:

“Things are not what they used to be, Peter. Something is wrong. Every farmer is feeling the pain. The crops are withering away. The harvest diminishes every year. We don’t get rain anymore. Even when it rains, it’s not cold enough to bring out the Shirepepe. Remember how we used catch them as kids? It seems like those creatures are gone forever. Your children may never get to know what a Shirepepe looked like. Strange things are happening, Peter. We don’t know where the world is going. Maybe the gods are angry. The sun burns like hell these days. Even birds are dying—I’ve been seeing many dead ones lately. We don’t know why these things are taking place.”

I assured Zossou that it wasn’t the fault of the gods. There is an explanation for this unfortunate development: global warming. And I challenge anybody who denies global warming to go and see the havoc it has caused in African villages where people are dependent on nature for everything.

I came back from the trip with haunting images of dehumanizing poverty and wasted lives, my once vibrant village a hungry community. Thanks to climate change, the healthy people have become statistics of preventable diseases and early death. While there, I held meetings with the  community to find out how best to help them. They were not asking for handouts; they wanted to be able to help their children break the cycle of poverty. Unless I’m a hypocrite, if I have compassion for animals, I must have compassion for my suffering fellow humans as well. If I can make sacrifices to save animals, I should make sacrifices to help the disadvantaged children in my village.

community to find out how best to help them. They were not asking for handouts; they wanted to be able to help their children break the cycle of poverty. Unless I’m a hypocrite, if I have compassion for animals, I must have compassion for my suffering fellow humans as well. If I can make sacrifices to save animals, I should make sacrifices to help the disadvantaged children in my village.

I have promised to try my best, with the generosity of American people, to help build a resource center for the village. I am, therefore, asking my fellow vegans and vegetarians to join us. My website is www.ajaraproject.org . Please email me at: peteropa@rethinkafrica.org for more information if you’re like to be a part of this effort.

Thanks for reading my story!

Peter Opa, an environmentalist and public speaker, lives between the U.S. and his African village, where he's committed to sustainable development and empowerment projects. The trees in the second photo are coconut palms; the classroom photo depicts one of the educational projects for women that Peter is supporting.

Pioneer: Bramwell Booth, 1859-1929

William Bramwell Booth was the oldest son of Salvation Army co-founders William Booth and Catherine Mumford Booth, and became the Army's second General. All three were vegetarians, though William later returned to meat-eating while traveling. But whereas the parents appear to have been motivated by considerations of spiritual discipline, Bramwell considered abstinence from animal flesh to be a moral issue, crucial to his ministry of working to bring the Kingdom of God to realization on earth. Here are some of his teachings, from publications of the Salvation Army:

William Bramwell Booth was the oldest son of Salvation Army co-founders William Booth and Catherine Mumford Booth, and became the Army's second General. All three were vegetarians, though William later returned to meat-eating while traveling. But whereas the parents appear to have been motivated by considerations of spiritual discipline, Bramwell considered abstinence from animal flesh to be a moral issue, crucial to his ministry of working to bring the Kingdom of God to realization on earth. Here are some of his teachings, from publications of the Salvation Army:

. . . . I will try and briefly reply to one question which I often hear: "Why do you recommend Vegetarianism?" . . . . Because, according to the Bible, God originally intended the food of man to be vegetarian: "God said, Behold, I have given you every herb bearing seed . . . and . . . fruit of a tree yielding seed: to you it shall be for meat." Gen. 1:29. . . . Because a vegetarian diet is favorable to industry, and hard work, and because flesh diet, on the other hand, favors indolence, sleepiness, growing fat, want of energy, indigestion, constipation, and other like miseries and degradations . . . . Because of the awful cruelty and terror to which tens of thousands of animals killed for human food are subjected . . . , in traveling long distances by ship and rail and road to the slaughter-houses of the world. God disapproves of all cruelty--whether to man or beast. . . .

[Vegetarianism] has an important bearing not only upon [the Army's officers'] own health and happiness, but upon their influence among the people, as men and women who are free from bondage of that selfish gratification which too often afflicts the professed servants of Christ. Let us remember the Apostle's direction: 'Whether ye eat or drink, or whatsoever ye do, do all to the glory of God.' (1900, 1901)

While I cannot say that I was, in the first place, led to abandon the use of flesh meat as an article of diet out of any sympathy with the animal creation, I have often felt, nevertheless, deeply thankful that I have no part in the grave responsibility for the horrors that are inflicted on millions of inoffensive creatures, killed with all manner of cruelty--some of it no doubt, quite unavoidable, if they are to be killed at all--in order to supply the wants of man. I believe that few really humane persons would touch another morsel of animal food, if they could once realise the agony endured by the vast majority of these creatures in order to meet their fancy. The miseries of the frightened droves, the tortures of the long journeys by rail, the unnamable agonies and abominations of the 'cattle-boats,' on which tens of thousands of unfortunate creatures travel from other lands. Alongside this the combined terror and torture which many of them suffer in the slaughterhouses, make a chapter too dark for ordinary mortals to read. And yet it all lies between the verdant meadows and the dainty morsel on your plate. (1902)

. . . . I have ventured to think and to say that this question is a moral as well as a material question: that it has a bearing on the life to come as well as the life that now is, and that it is to be rightly classed among the greater problems which confront the Church of God. (1901)

--Quoted in Familiar Strangers by John Gilheany, pp. 59-61

Poetry: Friedrich von Schiller, 1759-1805

An die Freude

Freude, schoener Goetterfunken,

Freude, schoener Goetterfunken,

Tochter aus Elysium,

Wir betreten feuertrunken,

Himmlische, dein Heiligtum.

Deine Zauber binden wieder

Was der Mode Schwert geteilt

Bettler werden Fuerstenbrueder

Wo dein sanfter Fluegel weilt.

Seid umschlungen, Millionen!

Diesen Kuss der ganzen Welt! . . . .

To Joy

Joy, Elysium's cherished daughter,

Radiant spark of Flame divine,

Drunk with fire here we enter,

Goddess, thy most holy shrine.

Thy strong magic binds together

What Convention's swords divide;

Beggar is a prince's brother

Where thy tender wings spread wide.

We embrace you, all ye millions--

One great Kiss to all the world! . . . .

Translated by Faith Bowman

The Peaceable Table is

a project of Quaker Animal Kinship / Animal Kinship Committee of Orange Grove Friends Meeting, Pasadena, California. It is intended to resume the witness of that excellent vehicle of the Friends

Vegetarian Society of North America, The Friendly

Vegetarian, which appeared quarterly between 1982 and

1995. Following its example, and sometimes borrowing from its

treasures, we publish articles for toe-in-the-water

vegetarians as well as long-term ones.

The journal is intended to be

interactive; contributions, including illustrations, are

invited for the next issue. Deadline for the February issue

will be Jan. 27, 2011. Send to graciafay@gmail.com

or 10 Krotona Hill, Ojai, CA 93023. We operate primarily

online in order to conserve trees and labor, but hard copy

is available for interested persons who are not online.

The latter are asked, if their funds permit, to donate $12 (USD) per year. Other

donations to offset the cost of the domain name and server are welcome.

Website: www.vegetarianfriends.net

Editor: Gracia Fay Ellwood

Book and Film Reviewers: Benjamin Urrutia & Robert Ellwood

Recipe Editor: Angela Suarez

NewsNotes Editors: Lorena Mucke and Marian Hussenbux

Technical Architect: Richard Scott Lancelot Ellwood

The case attracted much attention in the press, and by the time of the hearings, Somersett had no fewer than five legal counsel. One of them argued in effect that slavery is incompatible with what it means to be English, entailing that when Somersett set foot in England he became a free man. After weeks of deliberation the judge, William Murray, earl of Mansfield, gave his decision in the ex-slave's favor. Although Mansfield based his decision on legal technicalities, he made it clear that slavery was "odious" and could only be maintained under "positive law" supporting it, which did not exist in England. This so-called Mansfield Judgment was to be influential in the campaigns, over the next sixty years, to abolish the British institutions of kidnapping and holding African humans in chattel slavery.

The case attracted much attention in the press, and by the time of the hearings, Somersett had no fewer than five legal counsel. One of them argued in effect that slavery is incompatible with what it means to be English, entailing that when Somersett set foot in England he became a free man. After weeks of deliberation the judge, William Murray, earl of Mansfield, gave his decision in the ex-slave's favor. Although Mansfield based his decision on legal technicalities, he made it clear that slavery was "odious" and could only be maintained under "positive law" supporting it, which did not exist in England. This so-called Mansfield Judgment was to be influential in the campaigns, over the next sixty years, to abolish the British institutions of kidnapping and holding African humans in chattel slavery.

The members of Quaker Animal Kinship, sponsor of The Peaceable Table, want to express our thanks to those who responded to our appeal for funds. We especially want to thank Ms. Claire Williams, age seven, who donated more than $11.50 out of her allowance to help our animal friends. Friend Claire 's compasion and generosity are an inspiration to us all.

The members of Quaker Animal Kinship, sponsor of The Peaceable Table, want to express our thanks to those who responded to our appeal for funds. We especially want to thank Ms. Claire Williams, age seven, who donated more than $11.50 out of her allowance to help our animal friends. Friend Claire 's compasion and generosity are an inspiration to us all.  Studies by neurologist Kevin Nelson of the University of Kentucky indicate that because animals share with us humans the primitive brain areas linked to out-of-body, mystical, and other spiritual experiences, in all likelihood they have such experiences also. Ethologists Marc Bekoff and Jane Goodall support the idea that they (probably) do, citing incidents in which animals show signs of awe before scenes of tremendous grandeur. (Nelson claims that the brain areas in question originate the experiences, which is not necessarily the case.; these areas could instead be receptors of that which transcends us.) See

Studies by neurologist Kevin Nelson of the University of Kentucky indicate that because animals share with us humans the primitive brain areas linked to out-of-body, mystical, and other spiritual experiences, in all likelihood they have such experiences also. Ethologists Marc Bekoff and Jane Goodall support the idea that they (probably) do, citing incidents in which animals show signs of awe before scenes of tremendous grandeur. (Nelson claims that the brain areas in question originate the experiences, which is not necessarily the case.; these areas could instead be receptors of that which transcends us.) See  Thanks for endorsing my book [Familiar Strangers] from a North American perspective. I was never entirely sure how the parochial focus of the study might appear beyond UK shores; but as you've easily discerned; the rhetoric which receives quite an emphasis should resonate with Christians in most developed countries.

Thanks for endorsing my book [Familiar Strangers] from a North American perspective. I was never entirely sure how the parochial focus of the study might appear beyond UK shores; but as you've easily discerned; the rhetoric which receives quite an emphasis should resonate with Christians in most developed countries. The Chronicles of Narnia - The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. A Walden Media Film. Based on the classic novel by C. S. Lewis. Directed by Michael Apted. Star-ring Georgie Henley as Lucy, Skandar Keynes as Edmund, Ben Barnes as Caspian, Will Poulter as Eustace Scrubb, Liam Neeson as the voice of Aslan. 2010.

The Chronicles of Narnia - The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. A Walden Media Film. Based on the classic novel by C. S. Lewis. Directed by Michael Apted. Star-ring Georgie Henley as Lucy, Skandar Keynes as Edmund, Ben Barnes as Caspian, Will Poulter as Eustace Scrubb, Liam Neeson as the voice of Aslan. 2010.  Coriakin, the magician who rules this island, has an important role in the film that Lewis did not give him: he explains to the company that there is a great evil that threatens the whole world, which can only be defeated by laying the seven swords of the seven lords on Aslan's Table. From now on, the film's adoption of this unifying theme means that the tale essentially ceases to be episodic.

Coriakin, the magician who rules this island, has an important role in the film that Lewis did not give him: he explains to the company that there is a great evil that threatens the whole world, which can only be defeated by laying the seven swords of the seven lords on Aslan's Table. From now on, the film's adoption of this unifying theme means that the tale essentially ceases to be episodic.

2 cups organic unbleached flour

2 cups organic unbleached flour My decision to become a vegan was informed by several different and interrelated reasons: concern for animals, care for the earth, compassion for the poor, and good health.

My decision to become a vegan was informed by several different and interrelated reasons: concern for animals, care for the earth, compassion for the poor, and good health.  But as a child, I was uncomfortable with meat, something very rare for an African. I did not have any health issues whatsoever, but I felt incredibly sensitive to blood. As a result, unlike other children, I had a weird feeling about eating meat. My discomfort also had to do with how brutally animals were killed for food and rituals. Not knowing of any alternative way, I kept forcing myself to eat it.

But as a child, I was uncomfortable with meat, something very rare for an African. I did not have any health issues whatsoever, but I felt incredibly sensitive to blood. As a result, unlike other children, I had a weird feeling about eating meat. My discomfort also had to do with how brutally animals were killed for food and rituals. Not knowing of any alternative way, I kept forcing myself to eat it.  community to find out how best to help them. They were not asking for handouts; they wanted to be able to help their children break the cycle of poverty. Unless I’m a hypocrite, if I have compassion for animals, I must have compassion for my suffering fellow humans as well. If I can make sacrifices to save animals, I should make sacrifices to help the disadvantaged children in my village.

community to find out how best to help them. They were not asking for handouts; they wanted to be able to help their children break the cycle of poverty. Unless I’m a hypocrite, if I have compassion for animals, I must have compassion for my suffering fellow humans as well. If I can make sacrifices to save animals, I should make sacrifices to help the disadvantaged children in my village.  William Bramwell Booth was the oldest son of Salvation Army co-founders William Booth and Catherine Mumford Booth, and became the Army's second General. All three were vegetarians, though William later returned to meat-eating while traveling. But whereas the parents appear to have been motivated by considerations of spiritual discipline, Bramwell considered abstinence from animal flesh to be a moral issue, crucial to his ministry of working to bring the Kingdom of God to realization on earth. Here are some of his teachings, from publications of the Salvation Army:

William Bramwell Booth was the oldest son of Salvation Army co-founders William Booth and Catherine Mumford Booth, and became the Army's second General. All three were vegetarians, though William later returned to meat-eating while traveling. But whereas the parents appear to have been motivated by considerations of spiritual discipline, Bramwell considered abstinence from animal flesh to be a moral issue, crucial to his ministry of working to bring the Kingdom of God to realization on earth. Here are some of his teachings, from publications of the Salvation Army: Freude, schoener Goetterfunken,

Freude, schoener Goetterfunken,