Editorial: Stranger at the Table

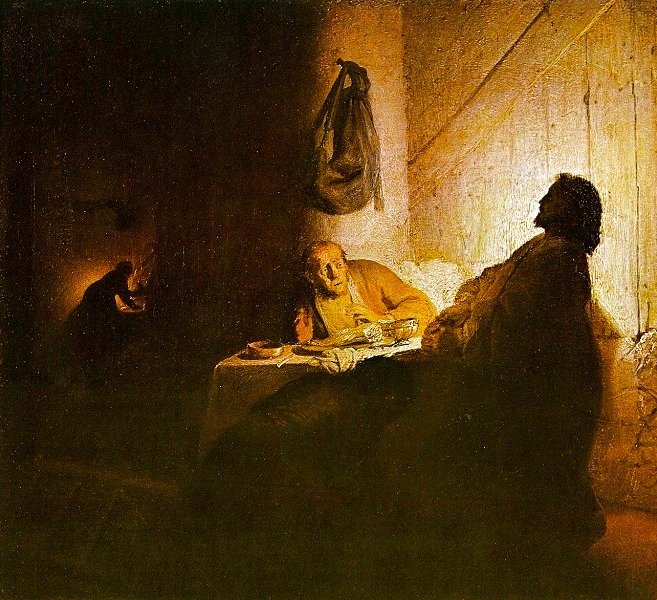

About in 1628 the twenty-something Rembrandt Van Rijn portrayed, in high drama, the climactic scene of the resurrection narrative in Luke 24:13-25. The story tells that two disciples of Jesus were walking from Jerusalem to their home in the village of Emmaus (a journey of about seven miles) on Sunday afternoon, two days after the crucifixion of Jesus. As they discuss the shattering event, a stranger overtakes them and asks what they are discussing that makes them so sad. One of them, named Cleopas, tells the newcomer about Jesus, the prophet of mighty word and deed from Nazareth whom their hopes had cast as the one who was going to liberate Israel, but who had been seized by the authorities and, horribly, crucified. They add that, that very morning, women of their group had reported finding his tomb empty, and angels announcing that he was alive; but others going to the spot did not see him.

The stranger responds by explaining to them that this all happened in accordance with God's plan, in fulfillment of various Scripture passages from Moses and the other prophets. When the two travelers reach their home, the stranger shows signs of going on, but they urge him to spend the night: "Abide with us, for it is toward evening . . . ." He accepts the invitation, and joins them for supper. At the table he takes the part of the host, breaking the loaf of bread and distributing it. Suddenly, they recognize that he is Jesus; and he vanishes. Electrified, the two disciples get up and go back to Jerusalem (a two-plus hour walk, mostly in the dark) to tell their friends that Jesus had appeared to them, and became known in the breaking of bread.

The Breaking of Bread

That the recognition took place in the context of a shared meal is significant; it identifies the stranger, connecting him with the main concern of Jesus' ministry, the Kingdom of God. This is an ancient theme in Israel's history, the minority position of those who hold that God's highest will for us is not royal human rule but a society of equality and thus of fairness. As described in "The Prophet From Nazareth" ( see PT 64) this concept is rooted in the Exodus, Israel's founding story, which shows that God, unlike many other nations' deities, is against exploitative rule; God wills to liberate its victims (via human action) into a life of happiness and plenty. Later prophets renewed Exodus for their own times. They denounced (among other things) the rapacious rule of contemporary overlords, whether they were Israel's own rulers, or a new foreign empire. They promised renewal and abundance to those who Returned to God as their king. One of the symbols of this new life of plenty is the shared feast: "On this mountain the Lord will make for all peoples a feast of rich things, a feast of wines on the lees . . . ." (Isa. 25:6) .

In his own day in which Roman greed and cruelty were driving the common people into tax debt, loss of farms, hunger, and misery, Jesus' teachings gave particular emphasis to the shared-meal image, in his parables as well as his actions. It becomes not only a symbol of future freedom and plenty, but a present reality of enough to eat for everyone. (The technical term is open commensality.) Furthermore, it means acceptance and friendship for those at the bottom of society instead of marginalization and contempt. In virtually any human society, some have much while others have little or nothing, and, correspondingly, most people will dine with those on their own social and financial level, but not with those they consider beneath them. This applies not only to the aristocrats, who scorn peasants, but to self-supporting peasants, who scorn the destitute and the prostitutes. But the feast Jesus promotes is one of compassion, equality and plenty for all who will to share. The God of love, not Caesar, rules.

Cleopas and his companion were almost surely among the poor; if they had means, one would expect them to be riding in comfort, not walking nearly five hours in one day. Like most first-century Jewish peasants who still had homes, their house was probably a stone-and-mud hovel, and their food scanty. The rough stone and board wall behind the dining figures in Rembrandt's painting, the small table with only enough food just to go around, reflect this probability (although not the high ceiling and spaciousness, probably chosen to convey a sense of the numinous). Yet they invite the homeless stranger to share what they have for the night. In doing so, they enact what they have learned from Jesus: and they find that he is not dead, but there at their table. They are stunned.

(Another means by which Jesus proclaimed God's Kingdom was through healing; and since some illnesses resulted in social ostracism, healing was linked to acceptance. He must have had an extraordinary healing gift, since so many stories tell of healings. He evidently did not consider this power unique, since when he sent his disciples out on a temporary mission, he told them to heal as he did. It was one of the main signs of the Kingdom of God.)

The painting's wonderful golden light from an unseen source, in which the figure of Jesus is silhouetted--light many times brighter than any oil lamp could cast--suggests that "something greater than Solomon is here." In the words of a hymn by Faith Bowman, "Where we call no man our master / But are kin and equals all, / Rich and homeless feast together-- / God is there to grace the hall." For this Quaker, the amber glow represents the Divine Light, which, largely unseen, suffuses all things and sometimes radiates out of the darkness in dazzling splendor: "The whole earth is full of [thy] glory." (Isa. 6:3) It is both Power and Presence. In the homeless stranger at the table we see the unknown Someone who cannot be defeated by violence and death, the Someone the from whom all somethings and someones come.

Excluded

Does this mean that all someones, however lowly, are welcomed at the table in the Kingdom of God? It is evident that historically, most human actions to promote the Kingdom have fallen sadly short. Perhaps the language contributes to the problems; despite its intent, its identification of God with a male monarch influences our thinking. Suggested alternatives, like the Commonwealth of God, don't communicate as well.

Particular instances of the Feast fall short in different ways. For example, even this marvelous Rembrandt painting shows that the artist seems to assume that the Kingdom of God is a class society. The three diners (one is on his knees before the figure of Jesus) are male, whereas in the background, a wife or kitchen maid is doing the work.* Sadly, it is unlikely that Rembrandt's contemporaries, and thousands of people of faith viewing the painting since then, have seen any problem here.

Furthermore, when we seek to provide a table and shelter for all, inviting the destitute from the "highways and hedges," we find that we must have not only generous, open hearts, but caution, prudence, and toughness as well. Those in greatest need do not necessarily welcome the Kingdom; a disturbed or addicted or mean-spirited few may sabotage the program for many. And the program may even perpetuate the problem, if supportive services such as therapy and job counseling are not provided as well. These necessary precautions tend to creates a two-class situation: those who bring the food and make the rules, and those who receive and obey. This fact tends to blunt the sensitivity of the well-intentioned folk who plan and carry out the dinners. Sometimes when I have participated in serving, I found that the "hosts" ate at their separate table, which the homeless "guests" did not feel free to join.

The View From Beneath the Bottom

Perhaps it is in regard to our oppressed animal cousins that historic efforts to welcome the stranger have failed most dismally. Most of the time people of faith have continued to regard "food" animals as beneath the bottom, if they are aware of them at all; they exist only as things on the platter. They remain strangers, not recognized even after death.

It is true that in some cases social conditions may make this problem very hard to remedy. One example is a program to feed homeless people who live on the vast city dump in Managua, Nicaragua. I visited this place in 1986 and 1995, and was horrified. Adults, children, whole families spend their lives combing the trash for not-too-decayed scraps to eat or an item they can sell on the streets; when a truck arrives to dump its trash, desperate people swarm over, and fights may break out. Because this situation especially reached my heart, I contribute to a program called Pro-Nica, supported by a group of Florida Quakers, which (among other activities) provides one meal a day to some of these destitute children. And the local people who plan and serve the meals, wanting these wretched children to have the best at that one dinner, include "meat." I made inquiries of my fellow Quakers: wouldn't it be more compassionate and Friendly to make the meals nonviolent? My correspondent, herself a vegetarian, agreed, but said it is hard to do. It seems that much of the country is a "food desert" when it comes to vegetables (which agrees with my experience there in 1986). Money for the program is limited, meat is more available, so that is what the children get with their rice and beans. I keep hoping for a way to open.

Of course there are food deserts in the US as well, but the middle-class people of faith who plan meals for homeless people are not confined to these deserts. Most of them center the meals on animal flesh because they have always eaten that way themselves; I know one or two who have even heard and resisted the message of compassion for animals. Instead of working toward an Exodus for the animals, most people of faith have unthinkingly participated in enslaving them in tighter cages. Instead of healing, we have paid to have them live in filth and misery, and die in terror and agony. Instead of sharing fairly at the planetary table with free animal nations, we consume the products of organizations that take over their living spaces, extinguishing nation after nation.

As with his forbears the earlier prophets, the prophet from Nazareth called people of all classes to repent. This word has become a caricature, but its original intent is profound, and is highly relevant here. One of its primary meanings is to turn away from corrupt social structures based on ranking and exploitation, and Return to the God of compassion and (distributive) justice. Both society and the individual must be transformed, until we love our neighbors as ourselves. We rejoice that some in our day have heard the prophetic message in regard to animals; no doubt there are readers of PT involved in shared-meal programs where the tables are genuinely peaceable. I know of a church and a Friends' Meeting whose members not only served homeless persons vegetarian meals, but decorated the tables with candles and flowers in honor of the strangers.

In the stranger, whatever her or his class or shape, we must recognize the divine Face.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

*Is this sexist feature redeemed by the fact that the maid is the one who most resembles Jesus, both in the angle of her body and the light silhouetting her? In fact the resemblance calls to mind his saying "Who is greater, the one sitting at dinner or the one serving? . . . . But I am among you as one who serves." Lk. 22:27). I invite comments on this and any other aspect of this essay.

Sources: The Last Week by Marcus J. Borg & John Dominic Crossan

Life in Year One by Scott Korb

Meeting Jesus Again For the First Time by Marcus J. Borg

In the Shadow of Empire by Richard A. Horsley, Ed.

Supper at Emmaus, oil on paper on panel, by Rembrandt Van Rijn.

Unset Gems

"Sentient beings, near and far, I vow to beFriend.

"Sentient beings, near and far, I vow to beFriend.

The Truth I vow to learn and speak.

With God I vow to unite all my being.

I can do all things through Christ who

empowers me."

--Triple vow of the Order of the Cross and the Grail

"To God belong the East and the West; whichever way you turn, there is the face of God."

--Qu'ran, Surah Baqara 2:115

I read the PT yesterday and really appreciated Lisa Adams' letter. She and I think a good deal the same on many points. Thanks for putting this in the newsletter. I'm sure that it connected with many of your readers, like me, who have somewhat different views.

I read the PT yesterday and really appreciated Lisa Adams' letter. She and I think a good deal the same on many points. Thanks for putting this in the newsletter. I'm sure that it connected with many of your readers, like me, who have somewhat different views.

Australian RAS agent, a Crocodile-Dundy-type kangaroo rat named Jake, whose value as their guide is dubious, since he flirts with Bianca and tries to ditch Bernard.

Australian RAS agent, a Crocodile-Dundy-type kangaroo rat named Jake, whose value as their guide is dubious, since he flirts with Bianca and tries to ditch Bernard. 3 cups raw cashews soaked for 3 hours

3 cups raw cashews soaked for 3 hours

He continues to take acting lessons, enjoying the different perspective on the world that drama provides. His involvement in drama contributes to his great success in making abstract material clear and enjoyable in the classroom. His classes are thronged with students and nonstudents enraptured by physics, thanks to Greene's charismatic style and novel metaphors. He sometimes uses characters derived from popular culture, such as Lisa from The Simpsons and Chewie from Star Wars. These gifts carry over into his popular-education books, The Elegant Universe, 1999 (on string theory) which has been made into a Nova film; The Fabric of the Cosmos, 2005 (on space and time); and The Hidden Reality, 2011 (on parallel universes).

He continues to take acting lessons, enjoying the different perspective on the world that drama provides. His involvement in drama contributes to his great success in making abstract material clear and enjoyable in the classroom. His classes are thronged with students and nonstudents enraptured by physics, thanks to Greene's charismatic style and novel metaphors. He sometimes uses characters derived from popular culture, such as Lisa from The Simpsons and Chewie from Star Wars. These gifts carry over into his popular-education books, The Elegant Universe, 1999 (on string theory) which has been made into a Nova film; The Fabric of the Cosmos, 2005 (on space and time); and The Hidden Reality, 2011 (on parallel universes).