Editor's Corner: "Like the Foul Stable"

The Birth of the Hero

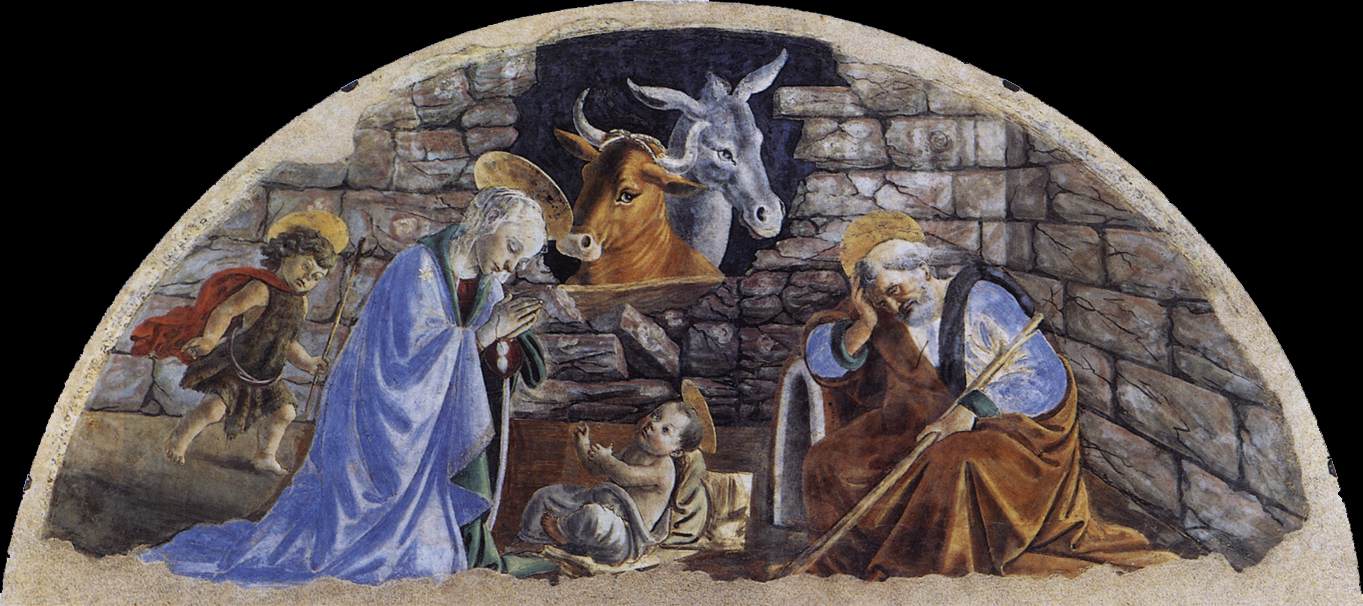

Many animal activists of the Christian faith rightly find the Nativity narrative in the gospel of Luke to be particularly affirming of farmed animals. This is the familiar story of the angel's appearance to Mary, of her and Joseph's journey to Bethlehem, the birth of Jesus in some kind of animal shed--"she . . . laid him in a manger," implying the presence of animals--and the angel hosts’ message of Peace on Earth delivered to the shepherds in the fields.

Like the narrative of the birth of Moses in the book of Exodus, this story is probably the best known example of the Myth of the Birth of the Hero (in fact the version in Matthew, with its tyrant who orders the massacre of babies, and the journey of Jesus' family to Egypt, deliberately alludes to Moses' birth). There are a number of such myths both in ancient religions and in biographical accounts of revered political or religious figures. (For the essay in the October Peaceable Table on C.S. Lewis' skillful use of the myth in his children's story The Horse and His Boy, see Hero Myth .

As I indicated in that essay, a Birth of the Hero story may be fictional, historical, or somewhere between; in this usage the word "myth" does not have the common meaning of a falsehood, but refers to a story embodying profound religious truth. Certain themes appear frequently in such myths. Supernatural portents precede or accompany the birth; the child is of royal or divine parentage, but at birth or soon afterwards is exposed to the elements, then rescued and reared by a peasant mother or couple, in a society oppressed by a cruel tyrant. The peasants usually live close to animals. The latter may stay in the background of the story, or an extraordinarily wise animal may be prominent as the hero's guide. The hero may have a twin. In youth or adulthood the hero manifests special powers, with which he (seldom she) engages the tyrannical powers that are crushing out the life of his society. He defeats the tyrant[s], and ultimately takes his true place as the royal or divine being he is.

Down in the Cellar

The story of Jesus’ birth in Luke is unusual in that it has a double reference to animals: the flocks of sheep in the fields, and the (implied) beasts in the stable. In Nativity paintings a few of the sheep often show up in the stable; and pictures that include figures from Matthew's story of the Wise Men may introduce a third set, the camels.

The presence of the beasts is significant in more than one way. To begin with, it underlines the lowliness of the birth. Whereas stable-hands and sheep-tenders are ranked in the bottom rungs of a traditional society, the animals have even lower status, usually being considered mere property. My brother Gareth recently pointed out to me that, according to archaeological evidence, cellars under human dwellings sometimes served as animal sheds. Such an arrangement would make sense, especially in towns and cities, where space was limited. (The shed of the inn in this story would probably have held the travelers’ donkeys.) It would mean that the image we have used before, of peasants, day-laborers and slaves at the bottom of society and animals beneath the bottom, has some literal truth. The beasts’ presence also underlines the physicality of the birth. No one denies animals’ physicality--in fact many people still think they are nothing but--and here, the story tells us, we find God-With-Us, the Holy present in flesh.

There is one aspect of this animal-shed (or animal cellar) hiding the Holy that is seldom mentioned in retellings of the Nativity story: nasty smells. One of the inevitable functions of fleshly existence, both animal and human, is excretion; and if cleanup is delayed or nonexistent, bad smells there will be. For years the only exception I knew to this understandable artistic blackout was an obscure carol entitled "The Story that Never Grows Old" which my schoolmates and I sang one long-ago Christmas. The third stanza began thus:

The world is so dull and the world is so dead

With ribaldry, pomp, and gain

And like the foul stable where cattle are fed,

So life has become profane.

In History of Religions terminology, a profane world is one from which the Holy is gone. I take these lines to mean that due to spiritual numbness, the numinous Presence, the dazzling Splendor lying at the heart of reality and holding it together, has been lost in the endless scramble for wealth and status. “Ribaldry” suggests that tender expressions of erotic love are lost in pornographic, contemptuous joking; sexuality is nothing but dirt. Comparing such a cultural situation to a stinking animal shed is very suggestive. Both spiritual and physical senses can give us unpleasant sensations as well as delights, and when we are faced with bad smells we cannot easily get rid of, we are tempted to deaden our senses--with the unhappy result that at the same time, we dull our capacity to experience the joys that may be closely linked to them.

Much later I encountered the same phrase in a nativity poem by G. K. Chesterton, entitled "The House of Christmas" which makes a somewhat similar point:

. . . . A Child in a foul stable

Where the beasts feed and foam,

Only where He was homeless

Are you and I at home;

We have hands that fashion and heads that know,

But our hearts we lost--how long ago! . . . .

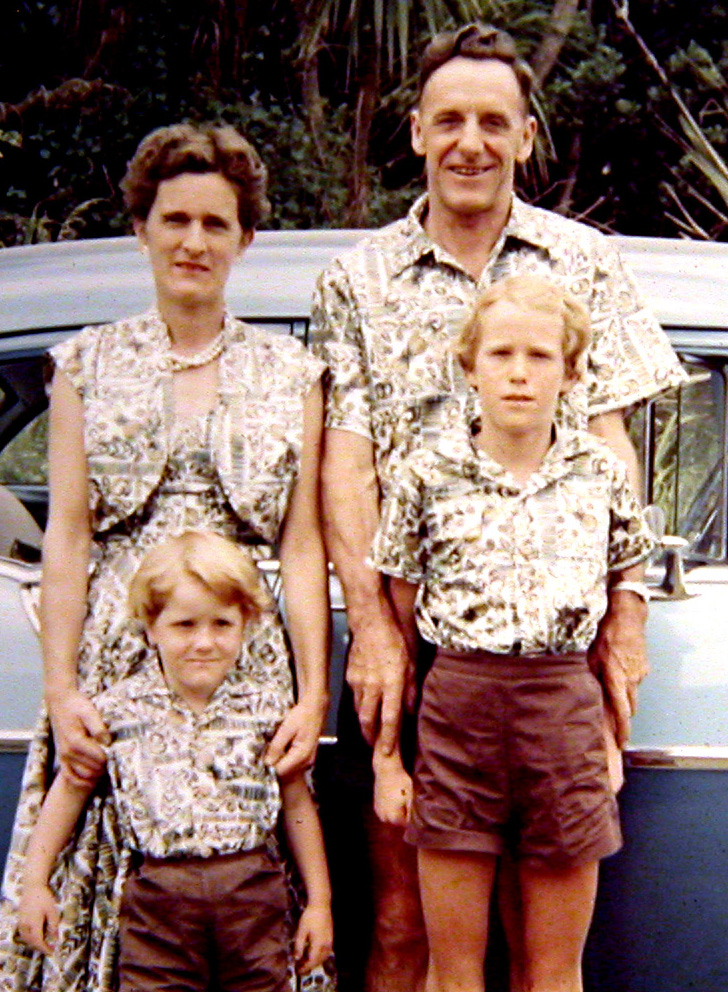

Manor Farm

When we look at (for-profit) animal sheds not as symbols but as themselves, their obnoxious odors become even more significant. I have some experience of this reality. I grew up on a traditional farm that raised both animals and cash-crops, from early 1945 until 1957. Our family ordinarily had seven or eight cows, who grazed in a field by day (except in winter) and were kept in a barn at night, to be milked by hand by my father and Gareth evening and morning. The milk would be poured into milk-cans to be shipped to market and made into butter and cheese. The cows stood in an open space, their necks held in a row of stanchions, with hay in the manger in front of them; behind them ran a gutter for their urine and feces, which had to be shoveled out twice daily. For a time we raised six to eight calves, who were kept separately and whose mess my father and brother cleaned out less often. It would become tightly compacted and took herculean labor to loosen and remove.

We also had about four hundred chickens, mostly hens, kept about a hundred to a large room in our long chicken coop. My father and brother fed them twice a day. Along one wall of each room were tiers of nesting boxes, to which the hens flew up to lay their eggs. Both floor and nests were lined with straw, which of course became foul over time. Approximately once a month or so my father and brother faced the job of getting rid of the Augean mess. They threw it, shovelful by shovelful, out the window (after which it all had to be moved again, into the manure spreader, to fertilize the fields). Then clean straw would be forked in to replace it. A month or two later the whole job had to be done over. It always seemed to take up every holiday, something that gave my brother particular delight.

We also had about four hundred chickens, mostly hens, kept about a hundred to a large room in our long chicken coop. My father and brother fed them twice a day. Along one wall of each room were tiers of nesting boxes, to which the hens flew up to lay their eggs. Both floor and nests were lined with straw, which of course became foul over time. Approximately once a month or so my father and brother faced the job of getting rid of the Augean mess. They threw it, shovelful by shovelful, out the window (after which it all had to be moved again, into the manure spreader, to fertilize the fields). Then clean straw would be forked in to replace it. A month or two later the whole job had to be done over. It always seemed to take up every holiday, something that gave my brother particular delight.

They also gathered the eggs, a job at which I occasionally helped. Most of the time the hens didn’t mind, but periodically they would become “broody,” that is, have a mind to sit on their eggs and hatch them. A broody hen would resent our stealing her babies-in-the-making, and would peck vigorously and angrily at the thieving hand reaching under her. (I figured out how to protect my hand with an unused shingle when taking her eggs.) Every afternoon my sister and I went down to our basement to face buckets full of eggs to be cased, many with caked feces which we had to sand off: our very own much-cherished job.

The Trap

We thought of these animals as our cows and our chickens. It never occurred to any of us that we were running a slave operation, but when one risks taking the view from below, i.e. "from beneath the bottom," one can begin to see that it was. Our blindness to the obvious is perhaps understandable since the animals we thought we owned were not draft beasts, whose enforced work does look rather like human-slave labor. But comparing the human and animal systems shows several ways that it was indeed slavery. As was the case with plantation owners in the antebellum South, “everybody”--

i.e., our peers and various authorities we respected --supported us in believing that these beings were meant to be property. Another feature that our farm had in common with human-slave owning was that we controlled the animals’ bodies, especially their sexuality, in order to appropriate what they produced. If they had reproduced and raised their offspring as they wanted, the whole thing would soon have become even less profitable than it was, and would have spun out of our control. It was perhaps somewhat like human sexual slavery, in that most of “our” chickens were females, and all of “our” cows, but different from that system in that, to achieve such an unbalanced state of affairs, the unwanted male chicks and calves were taken away and killed (as still obtains in agribusiness operations today). The anger of the broody hens and the grief of the cows bereaved of their baby sons (being seldom in the barn, I was not even aware of that till years later) could be disregarded, because the intentions of the owners were the only ones that mattered. Another similarity is that both we and the keepers of human slaves were supported by pronouncements from the science of the day, and certain Biblical passages (though both we and they had to ignore others).

A factor even worse than most human-slave operations was that almost none of “our” animals died natural deaths: we killed and ate some, and sold the rest whose profitability had diminished, to be killed and eaten by other humans. What else were they there for?

Green Growing Things

But there were other things about our farm that were genuinely good, which must not be ignored: a beautiful setting amid meadows, trees, and snow-topped mountains, where I sometimes felt intimations of Eden; paradisal flowering trees in springtime; my mother’s flower garden and a burgeoning vegetable garden; a small orchard producing luscious apples and cherries and plums. The wind was fresh and fragrant; on cloudless nights we could see thousands of stars. We never once locked our house.

Our cash crops, strawberries, raspberries and boysenberies, were not open to the moral objections of our slave-animal operations. They too took enormous work, especially the raspberries, whose canes we had to prune and tie back in the cold weather of early spring. Irrigating them meant the endless work of carrying about the heavy pipes--another job my brother detested. This is not even to mention weeks spent picking the berries during the heat of summer “vacations.” Our fruit was far tastier and more nutritious than the chemically-boosted berries produced by other farms, but seldom brought us any more profit than did the animals. My father’s fondness for expirmentation and organic farming methods were too far ahead of their time.

Taken all together, the work was so hard and overwhelming that sometimes we felt like slaves ourselves, though of course we were not--we had access to education, and eventually we chose to get off the farm. Despite ten or twelve-hour workdays by my parents, and shorter days by us four children (especially during the school year), our family could never climb out of debt. When we seemed close to solvency, there would be something like a drought or too much rain, a slump in the prices of eggs or berries, an increase in the prices we had to pay, and we would be trapped as tightly as ever. At times my father had to take a second job, but even that didn’t bring in enough. Chronic financial anxiety can take much of the joy out of life for a responsible, well-meaning person, can spark verbal violence that blights lives and takes years to heal.

We became the victims of our victims in another way as well. When two family members later struggled with cancer and chemotherapy, when two others died of the disease, they knew little or less about its roots in (among other things) the animal bodies and products we had labored so hard over, and taken to be an essential part of the fabric of human life.

New and Improved!

Virtually all readers will already be aware of how much worse the situation is in present-day animal-slave operations: crowded, filthy, reeking mega-sheds almost never cleaned out, imprisoning thousands or hundreds of thousands of wretched, immobilized chickens, turkeys, pigs, calves and cows with ammonia-burned lungs, never free of pain and never seeing sunshine--places that dangerously pollute the air and earth and water for miles, breeding diseases that sicken and kill thousands of them and us, and may eventually mutate to kill billions of us in a single ‘flu pandemic. Both morally and physically, the stench of such houses of horror rises to High Heaven. Little wonder that those who consume the flesh and eggs and milk coming out of these hells unknowingly make themselves “so dull and so dead,” lest they might actually awaken and smell what is going on.

It is also not surprising that to many people who care about planet Earth, our family's small-time, ecologically responsible way of raising animals--if it can be made profitable--looks golden, the kind to which our culture should return. It was not, and is not. If our farm had been profitable, we probably would not have suffered in the same way, but we would still have been making our hearts callous (e.g., for years my father and brother engaged in hunting, mostly for fun, and we females scarcely protested); still closing down our awareness to the presence of the Holy in our Stable; still making our bodies dangerously sick; still dulling and deadening our souls to avoid empathizing with the beasts, in order to keep up the make-believe that only our human feelings and intentions existed. Whatever its size, whether or not it has laudable areas of decent treatment, every for-profit animal-slave operation has the stench of death.

Still Travails the Heart

This Foul Stable, either traditional or "new and improved," is not the last word. The next line in the carol from my childhood goes “Still travails the heart in the birth of the King . . . . “ It suggests that despite the numbness so many of us have unconsciously cultivated to evade the stench, we are not, after all, dead: at its deepest level, the human heart is not only still living but pregnant. Indeed, it is in labor with the Holy. Similarly, Chesterton’s poem tells us that this lowliest place--of a homeless mother and newborn, of farm[ed] animals in all their fleshliness--is both the Way to the eternal Home of all, “an older place than Eden . . . .” , and is that eternal Home itself.

Affirming this spiritual/artistic insight may be a pure act of faith like walking in the dark, a Pascalian wager of sorts, but it may be more than that. Some of us have experienced the marvelous fragrance of the Holy for ourselves--as Presence, as Power, as Light, as Love--either faintly or overwhelmingly, so that we know, and can never forget, however bad the stench of the Stable. Others may have heard or read stories of such encounters with the Transcendent, and seen their transforming power in a human life, so that faith has some basis in vicarious experience. The two may coexist.

Another possibility (or factor in the mix) is that repeatedly affirming what one believes, and acting on it, work to strengthen an uncertain faith. Telling and retelling life-giving stories such as the Myth[s] of the Birth of the Hero, singing or chanting songs or liturgies, creating or experiencing art depicting such traces of the Holy--by any or all of these means, we may keep in our sight a guiding star of hope that enables us to keep going.

Of course there is always the possibility that what we are thus envisioning is distorted, is partly or wholly illusory; that is the risk that faith takes. It is a better choice than deadening our spiritual senses and giving way to the scarcely-perceived stench of death.

Let us awaken our hearts, choose hope, and take the Adventure of coming fully alive.

My thanks to my brother Gareth for sharing with me his memories of life on our farm.

The Nativity painting suggestive of a cellar is by Sandro Botticelli, 1476.

The painting of the star and shepherds is from marvelsphoto.com .

This is the record of the author's loving interaction with no fewer than twenty-one cats, ranging from Supan who companioned her in Paris on her first youthful job abroad, to others who shared her semi-rural Long Island home in later and more stable days. We learn of the various ways these feline friends came to her, their various quirks and ailments, and all too often their untimely ends. The author comes across as a level-headed, no-nonsense kind of woman, successful as a freelance writer and advertising consultant, who at the same time cares deeply about animals. (Her earlier book, The Pet Surplus, on shelter animals, won praise from humane professionals.)

This is the record of the author's loving interaction with no fewer than twenty-one cats, ranging from Supan who companioned her in Paris on her first youthful job abroad, to others who shared her semi-rural Long Island home in later and more stable days. We learn of the various ways these feline friends came to her, their various quirks and ailments, and all too often their untimely ends. The author comes across as a level-headed, no-nonsense kind of woman, successful as a freelance writer and advertising consultant, who at the same time cares deeply about animals. (Her earlier book, The Pet Surplus, on shelter animals, won praise from humane professionals.)

The irrevocable transition to veganism didn’t make the next step in my life very easy, however. It was fine while I was living in laid-back, tolerant, veg-friendly Southern California, but jolly complicated when I fell in love with and married a Frenchman, and moved to Paris where I have lived ever since. The French are only tolerant of my “fanaticism” because I’m a foreigner and can be written off as an exotic, amusing eccentric. They are far less tolerant of their vegan fellow citizens whom they consider to have betrayed a priceless gastronomic heritage!

The irrevocable transition to veganism didn’t make the next step in my life very easy, however. It was fine while I was living in laid-back, tolerant, veg-friendly Southern California, but jolly complicated when I fell in love with and married a Frenchman, and moved to Paris where I have lived ever since. The French are only tolerant of my “fanaticism” because I’m a foreigner and can be written off as an exotic, amusing eccentric. They are far less tolerant of their vegan fellow citizens whom they consider to have betrayed a priceless gastronomic heritage!  But given up we have not. Three good ways to get through to French people, in my now long experience working for animal rights, is to use humor, street theater, and shock tactics. French activists have nothing to teach Americans in this area, of course--PETA has led and inspired the world (as well as arousing considerable resistance along the way). But it is encouraging that the kind of street action pictured here is making a real impact in France. The photo on the right shows my husband Michel doing a "repentant butcher" act. He waved a plastic hatchet and synthetic chicken at the public, shouting that they could do their own killing from now on and that he was fed up with doing their dirty work for them. They laughed a lot and got the message without taking offense. His most successful role, however, was that of a" flasher!" He ran up to women in the street and opened his overcoat. They started to be put off, but then laughed to see that, quite properly dressed, all he was "flashing" was the inside of his coat covered with large vegetarian product labels . . . . The one below, featuring the Grim Reaper herding "animals," is from the 2011 Veggie-Pride event. This is a parade with street theatre that takes place every May or June in Paris, and attracts hundreds of onlookers.

But given up we have not. Three good ways to get through to French people, in my now long experience working for animal rights, is to use humor, street theater, and shock tactics. French activists have nothing to teach Americans in this area, of course--PETA has led and inspired the world (as well as arousing considerable resistance along the way). But it is encouraging that the kind of street action pictured here is making a real impact in France. The photo on the right shows my husband Michel doing a "repentant butcher" act. He waved a plastic hatchet and synthetic chicken at the public, shouting that they could do their own killing from now on and that he was fed up with doing their dirty work for them. They laughed a lot and got the message without taking offense. His most successful role, however, was that of a" flasher!" He ran up to women in the street and opened his overcoat. They started to be put off, but then laughed to see that, quite properly dressed, all he was "flashing" was the inside of his coat covered with large vegetarian product labels . . . . The one below, featuring the Grim Reaper herding "animals," is from the 2011 Veggie-Pride event. This is a parade with street theatre that takes place every May or June in Paris, and attracts hundreds of onlookers.