All Animals Are Equal...

"...But some are more equal than others," goes Orwell's familiar line. Or, in Quaker language, should we say "All bearers of the Divine Light are equal, but we human beings are more equal than others."

"More Equal" is of course nonsense that shows up the bad faith of a speaker who has betrayed his or her commitment. No Friend or other spiritual aspirant would seriously make such a claim. Those who defend the status quo of animals-as-food would simply say that Equality does not apply to them, and never has.

But equality is a complex and ambiguous concept, and it is not surprising that even Friends, for whom it is a cardinal principle, can sometimes be confused. Not all nonhuman animals are equal; they range from the highly sensitive and complex to the clam or paramecium. For the purpose of this essay, I exclude the latter, defining "animal" as any being with a central nervous system, presumably making her or him capable of feeling physical pain or pleasure, and also as capable of some degree of psychological distress or gratification. And people who defend hierarchical human social structures have pointed out that in fact all people are not equal either, let alone all beings. There is a great mental gulf between Einstein and the badly brain-damaged, a moral/spiritual gulf between Gandhi and the torturer. This obvious inequality of capacities in individual humans, applied across the board to oppressed groups, was once used to deny equal rights to women, Blacks, and others. Traits sometimes fostered by particular conditions of oppression became stereotypical descriptions of the whole group. Thus women are by nature timid, modest, and weak-minded, destined to please men and raise children; Blacks are lazy, highly sexed, and prone to crime; Jews are dishonest gold-diggers who will try to take control of (more spiritually-minded) Christians. It follows, obviously, that these inferior beings must be subordinate to their betters.

As a result of the movements for race, gender, and ethnic liberation (as well as wars) in the nineteenth and twentieth centures, such ideas for the most part are no longer openly accepted in our culture. But the pattern of self-fulfilling stereotyping is mostly still in place for animals, and contributes to keeping them in chains. People who would never think of using "Jew-moneylender" or "lazy nigger" as an epithet don't hesitate to use animal words as terms of abuse against fellow humans: "bitchy" or "hoggish" or "bovine." Or (to describe those who commit atrocities) just "animal."

Surprising Discoveries

Just as with these other liberation movements, the heightened concen, in the last thirty or forty years, with animals as subjects with rights or interests of their own has brought to light a great deal of information that challenges the stereotypes. Ethology, the study of animals in their own societies and environments represented by Jane Goodall's work with chimpanzees, has revealed much that can't be discovered by cutting up the bodies of live animals kept in cages. As recorded in a 1995 National Geographic, among the discoveries of Goodall's Gombe project are the observation that chimps not only make tools, but that communities establish cultures: a particular tool-use that was part of the culture of one chimp community took root in another after a chimp immigrated from the first to the second. Jane was right to (unknowingly) violate scientific protocol by giving them names rather than numbers; chimps have been seen to have diverse personalities, complex emotions and social relationships, ranging from the affectionate to the bullying. They even show signs of responding to scenes of grandeur with awe

Yet in Africa they are still widely regarded as human food!

Chimps are shaped rather like us (or vice versa), and we share with them 98% of our DNA, so perhaps these facts shouldn't surprise us. But scienties studying cows—not quite in their natural habitat but with respectful regard for what it might feel like to be a cow— have also made some surprising discoveries. For example, at a recent conference in England on animal sentience, researchers Donald Broom and Kristin Hagen told of a project in which they devised a control panel in a paddock that required young cows to figure out how to open the gate admitting them to a food treat. Broom and Hagen fitted out the heifers with brain and heart monitors to measure their level of excitement. The heifers mulled over the situation for a time. When some of them figured out the solution and opened the gate, they had a "Eureka!" response: their hearts raced, their brainwaves altered, they jumped for joy, and trotted happily over to the food.

John Webster, a professor of animal husbandry at Bristol University, reports that cows in a herd form small friendship groups of up to four animals; they spend their time together, often grooming each other. They will be careful not to hurt one another with their horns. They may dislike certain other cows, and bear grudges for months, even years.

Keith Kendrick of Brabingham Institute reported parallel capacities among sheep. They can remember as many as fifty faces of other sheep, recognizing them even in profile; they can become strongly attached to particular humans, becoming depressed by separations and greeting the long-lost person enthusiastically after separations of up to three years.

Not so bovine—or ovine—after all! When we take in this kind of evidence that "farm" animals have complex lives and viewpoints, our human practices of casually incarcerating and killing them for food begin to seem more and more like the organized human slavery and massacres of the grimmest periods of history.

Wherein Lies Equality?

What if these studies had come up with different results, tending to support common prejudices about animal vacant-mindedness? Suppose our only signs that animals experience pain was their pulling back, trembling and screaming while facing actual violence? Does their claim to equality depend on their mental capacities and psychological complexity?

It does strengthen our appeal for changing the human treatment of them. But it can't establish their equality, because humans can still be "more equal," i.e., more intelligent, more complex. Equality, says philosopher Peter Singer, is a moral rather than a descriptive concept. He quotes 18th century thinker Jeremy Bentham: "The question is not, Can they reason? nor Can the talk? but, Can they suffer?" Similarly, Thomas Jefferson, in his efforts to do away human slavery, comments that "Because Sir Isaac Newton was superior to others in understanding, he was not therefore lord of the property or person of others." Most people would agree that subjecting a brain-damaged human being to painful experiments (or killing her for food!) is no more justifiable than doing the same to a genius.

Moving Toward Equality

Then how can we justify participating in this physical violence, let alone in the psychological violence of tearing a cow away from her friends, or a calf from his mother so that we humans can consume her milk? Most people, including most Friends and other socially concerned people, don't try to justify these massive violations of equality; they just go on eating their chops and their cheese. And the wealthy, politically powerful meat and dairy industries go on supplying them and raking in their subsidies and their profits. The dead hand of tradition and habit is heavy indeed.

Needless to say, it will not do. We must continue to examine our lives. We must "speak Truth to Power"—even when the powerful are not only politicians and CEOs, but ordinary, obscure human beings, including ourselves. After all, we have the choice to reach for that chunk of flesh in the supermarket, or to choose a nonviolent alternative—a power infinitely beyond that of the cow in the jammed truck headed for hell on earth.

I have made this cake and served it at many social functions where the

people were not vegetarian, let alone vegan; and every time it was very

well received. I was even once asked if I was sure there were no eggs in

it-- of course I was sure; I had made it in my own kitchen where there are

never any eggs.

I have made this cake and served it at many social functions where the

people were not vegetarian, let alone vegan; and every time it was very

well received. I was even once asked if I was sure there were no eggs in

it-- of course I was sure; I had made it in my own kitchen where there are

never any eggs. Since childhood I have heard the urging of the Inner Voice to live

non-violently and to seek the ways of understanding, Peace and

harmony—basically, simply, to live the Golden Rule.

Since childhood I have heard the urging of the Inner Voice to live

non-violently and to seek the ways of understanding, Peace and

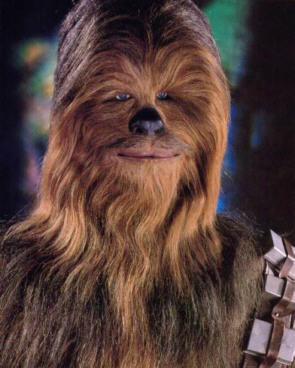

harmony—basically, simply, to live the Golden Rule. The last of the Star Wars saga to be produced, though number three among the six in chronological sequence, Revenge of the Sith continues the series' focus on vast and richly-hued vistas spread through many worlds, featuring innumerable creatures of many aspects. Some are beautiful and some menacing (by human standards), some emerge as tiny (like the physically diminutive but spiritually towering Yoda) and some loom gigantic. Moreover, some are living, some droid, and some perhaps a mixture of both. Throughout all these fabulous realms, action is fast-paced, but pauses sufficiently to indicate the psychological anguish tormenting the central figure, Anakin Skywalker, later Darth Vader, as he struggles with, and finally submits to, the Dark Side of the Force.

The last of the Star Wars saga to be produced, though number three among the six in chronological sequence, Revenge of the Sith continues the series' focus on vast and richly-hued vistas spread through many worlds, featuring innumerable creatures of many aspects. Some are beautiful and some menacing (by human standards), some emerge as tiny (like the physically diminutive but spiritually towering Yoda) and some loom gigantic. Moreover, some are living, some droid, and some perhaps a mixture of both. Throughout all these fabulous realms, action is fast-paced, but pauses sufficiently to indicate the psychological anguish tormenting the central figure, Anakin Skywalker, later Darth Vader, as he struggles with, and finally submits to, the Dark Side of the Force.  When the nature scientist, Sir Joseph Banks, was asked, "What do we learn

about the Creator from the study of the creation?" Sir Joseph replied "An

inordinate fondness for beetles." God must love those insects greatly, to

have created so many species of them in such profuse variety. Well, I love

beetles too, so I think Sir Joseph was on the right track, but he did not go

far enough.

When the nature scientist, Sir Joseph Banks, was asked, "What do we learn

about the Creator from the study of the creation?" Sir Joseph replied "An

inordinate fondness for beetles." God must love those insects greatly, to

have created so many species of them in such profuse variety. Well, I love

beetles too, so I think Sir Joseph was on the right track, but he did not go

far enough. His investigations in science, philosophy, musical theory and geometry ( he

is known today chiefly as the proponent of the pythagorean theorem) were all

part of his spiritual enterprise, the search for God and the salvation of

the soul. Perhaps the central tenet of his worldview was the idea that the

soul was immortal, a fallen divinity that incarnated not only in successive

human forms, but also in animal forms. Thus all animals are our cousins;

injuring, killing, eating them were abhorrent to him, and compassion was

enjoined. His latter-day biographer Iamblichus says "Amongst other reasons,

Pythagoras enjoined abstinence from the flesh of animals because it is

conducive to peace. For those who are accustomed to abominate the slaughter

of other animals, as iniquitous and unnatural, will think it still more

unjust and unlawful to kill a man or to engage in war."

His investigations in science, philosophy, musical theory and geometry ( he

is known today chiefly as the proponent of the pythagorean theorem) were all

part of his spiritual enterprise, the search for God and the salvation of

the soul. Perhaps the central tenet of his worldview was the idea that the

soul was immortal, a fallen divinity that incarnated not only in successive

human forms, but also in animal forms. Thus all animals are our cousins;

injuring, killing, eating them were abhorrent to him, and compassion was

enjoined. His latter-day biographer Iamblichus says "Amongst other reasons,

Pythagoras enjoined abstinence from the flesh of animals because it is

conducive to peace. For those who are accustomed to abominate the slaughter

of other animals, as iniquitous and unnatural, will think it still more

unjust and unlawful to kill a man or to engage in war."