The Animals and the Angels, Part III

In the May '06 editorial of PT, we looked at a few bits of evidence that the consciousness of human animals, and even of our furry and feathered siblings, might survive death. In so little space, one can of course do no more than encourage the reader to question received opinion, and check out the evidence for her/himself. In this last section, I will proceed "as-if"--supposing it were established that nonhuman animals of all sorts and conditions did survive death, what would be some of the implications for our treatment of them?

Cautions

It must be admitted at the outset that such a state of affairs would not necessarily lead to an elimination of humans' casual killing of animals. There have been many cultures that took survival of animal and human consciousness for granted, but manifested this belief in cruel and exploitative ways. For example, in some tribal cultures, animal sacrifice was based on the belief that the spirit of the slain beast would go to the other world and there be accepted by the deity as a gift. In regard to human beings, there have been found ancient burial sites of powerful men that included the remains of many others, probably slaves and wives killed at his death in order that they might serve the great man in the next world.

Several ancient peoples in the Near East held that survival was a curse for all, whatever their rank; there was a widespread view of the human afterlife as a gloomy, meaningless existence in a dusty underground realm. (So much for the modern idea that all ideas of survival are wish-fulfilment!)

It is true that the majority of Near-Death Experience narratives to be found in the public domain are happy or peaceful. But we cannot safely deduce from the evidence that, if animals (and people) do survive death, they will surely be compensated with joy and peace for unjust suffering on earth. There are certainly many NDE accounts, primarily from children, of entering a paradisal realm and being met by a happy, bounding dog or cat the child had loved and lost. There are stories of Edens with contentedly grazing deer or horses, including a wonderful account, told by experiencer Audrey Harris, of a woodsy Peaceable Kingdom, complete with lion, lambs, and a trumpeting angel (see Full Circle by Barbara Harris). But there are also NDEs (their percentage of the total unknown) that are dismal, distressing, or terrifying, and no reliable connection can be traced to the mural/spiritual character of the human experiencer. We cannot assume that things would be different for our fellow animals.

These depressing generalizations do not, however, mean that the issue of life after death for sentient beings has nothing to offer those of us who defend animals. It expands the stage; after each physical life it places, in Gracie Allen's image, a comma rather than a period. We cannot be certain what might be on the other side of that comma, but continued or expanded existence of consciousness would give weight, so to speak, to any being. She or he is no mere it, no object to be disposed of at the whim of a supposed owner. There is more. And though there is no certainty of happiness in this more, there are good reasons for hope.

Evolution and Survival

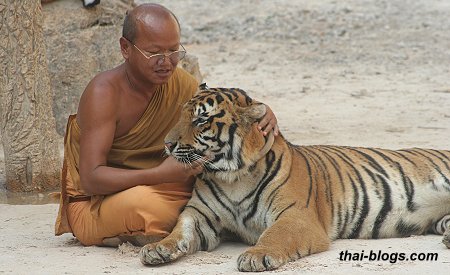

Evolutionary theory would seem to be one of the blocks to survival, but this is not necessarily the case; evolution can even be a support. The moral Grand Canyon that is customarily drawn between human beings and animals--such that killing a human is murder, killing an animal is "harvesting"--is shown up by evolution to be a completely artificial construct: all we animals are of one blood, we are kin. If humans survive death, animals very likely do too, either as individuals or perhaps as (for example, social insects) part of a group consciousness.

But how about the reductionism in evolution, the disappearance of the soul resulting from the principle that in bringing a new form of life into existence, physical changes are primary and the development of consciousness secondary? This would seem to make evolution hopelessly inhospitable to the concept of survival. But this apparently fundamental element is not, in fact, a necessary part of evolutionary theory. It is a philosophical assumption (alluded to in Part II) that accompanies the Darwinian version of evolution. In fact there are several other philosophical frameworks for evolution that are more congenial to survival, in which intelligent design and evolution (to use contemporary political terms) make very comfortable bedfellows.

Among them are the theory of Roman Catholic paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin and his followers (see The Phenomenon of Man). The process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, initially inspired by developments in twentieth-century physics, also makes consciousness primary in evolutionary process, and has been found compatible with (human) survival by some of its proponents (see Parapsychology, Philosophy, and Spirituality by David Griffin). There are other forms of evolution in which survival is even a vital part of the theory: see, for example, a cluster of Theosophical esssays influenced by Eastern thought in Lester Smith's aptly named anthology Intelligence Came First, 2nd ed.), and the analogous systematic philosophy of involution and evolution by Hindu Vedantan mystic Aurobindo (The Life Divine).

Why Reasons for Hope?

Despite the fact that some NDEs are distressing and serve no evident moral purpose of correction or reward, there are reasons to consider the likelihood of life after death as a decided plus. The most important reason represents the total existence of a living being as a journey of adventure climaxing in transformation. Many people who have NDEs exemplify this picture in their subsequent life. Unable to go on as before, their personalities undergo basic changes, as previous values--prestige, power, wealth, or an exclusive relationship--now seem suffocating and empty. Now they thirst for God; they devour books; they give away property; they explore different religious practices; they embark on a life of service. They may receive guidance from a guardian angel; gifts of healing or clairvoyance may appear. While these changes often bring joy and excitement, they also result in the pain of misunderstanding, disruption of intimate relationships, loneliness and longing, the sense of being a stranger in a strange land.

These changes are in many cases similar to those reported by mystics, whose spiritual awakening leads to a lifelong search for God that takes them through trackless deserts and cosmic loneliness, including "dark-night-of-the-soul" experiences remarkably similar to painful NDEs. The journey, typified by Western scholars of mysticism as consisting of three or five major stages, ultimately leads to the inexpressible joy of union and empowerment.

Perhaps this long hero-adventure recounted in many versions and many cultures--the awakening, joy and suffering, ordeal and fulfilment of a person of destiny--is also the Eastern and neoplatonic mystics' journey from the One as potential, out into a far country to gain a treasure, and ultimate return to the One as Love realized. Perhaps this journey is something every living being is engaged in, for God surely loves all whom s/he has brought forth, and intends us for Her/Himself. This is a matter of faith, forwe see glimpses only, moments of it in our life (or lives) on earth, and the vast majority of it must be hidden from our sight. The sense of profound unity with all beings, including animals, that many mystics and Near-Death Experiencers describe would seem to support such a faith.

Benefits and Liabilities

I find this framework profoundly encouraging when I am overwhelmed with the vast extent of human and animal suffering and the resistant power of the forces of ignorance and evil that perpetuate it. I feel supported in my prayers for my fellow animals, for their and our evolution beyond violence and back to the divine Heart. (This sketch, irresponsibly brief, is supported and developed further in my aforementioned book The Uttermost Deep: The Challenge of Near-Death Experiences.)

It is true that when a whole culture takes for granted an essentially positive view of the afterlife, a certain percentage of the population will take that as an excuse to close their hearts to the suffering of their fellows. This kind of complacence explains the widespread conviction of liberally-inclined people of faith that belief in an afterlife is based on wish-fulfilment and leads to a world-abandoning, pie-in-the-sky outlook. (However, it is generally not the case with those who have experienced near-death, who are not only convinced of survival, but are in many cases much more deeply engaged in this world than before.) And it must also be acknowledged that reductionism and despair also tend to lead to to numbness and closed hearts--hardly an improvement. It is eminently worth our while to look at the very considerable reasons for hope that this life is not all there is.

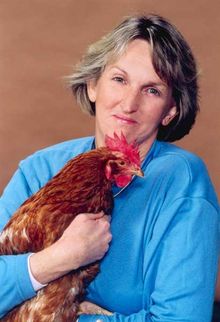

—Gracia Fay Ellwood

We invite responses to editorials or any other feature of PT for our next issue's letter column: graciafay@mac.com.

In fact risks do exist. Health hazards faced by vegans are most likely to be satisfactorily addressed by authorities who also appreciate the benefits of the vegan diet, and we are fortunate to have the ongoing Vegan Health Study by Michael Klaper, M.D., which confirms the advantages we already know of, but points out that care must still be taken. For example, vegans can actually have elevated blood cholesterol levels, despite not consuming any animal cholesterol. What we do not eat is certainly important, but what we do eat is no less important. A vegan who consumes large amounts of refined carbohydrates (both sugars and starches), trans-fats and deep-fried foods, and insufficient fiber, is actually likely to develop elevated cholesterol levels. Similarly, those of us who take in too much salt, are stressed, and don't get enough exercise can and do develop high blood pressure. Vegans are at definite risk for osteoporosis, says Klaper, if we do not consume and absorb enough calcium and other trace minerals, get enough vitamins K and D, and engage in enough weight-bearing exercise.

In fact risks do exist. Health hazards faced by vegans are most likely to be satisfactorily addressed by authorities who also appreciate the benefits of the vegan diet, and we are fortunate to have the ongoing Vegan Health Study by Michael Klaper, M.D., which confirms the advantages we already know of, but points out that care must still be taken. For example, vegans can actually have elevated blood cholesterol levels, despite not consuming any animal cholesterol. What we do not eat is certainly important, but what we do eat is no less important. A vegan who consumes large amounts of refined carbohydrates (both sugars and starches), trans-fats and deep-fried foods, and insufficient fiber, is actually likely to develop elevated cholesterol levels. Similarly, those of us who take in too much salt, are stressed, and don't get enough exercise can and do develop high blood pressure. Vegans are at definite risk for osteoporosis, says Klaper, if we do not consume and absorb enough calcium and other trace minerals, get enough vitamins K and D, and engage in enough weight-bearing exercise. 1 lb. spaghetti, linguine or fettuccine

1 lb. spaghetti, linguine or fettuccine Sometims an odd experience or an unexpected relationship changes a person's life. A pig changed mine. So did a long-dead Indian poet named Rabindranath Tagore.

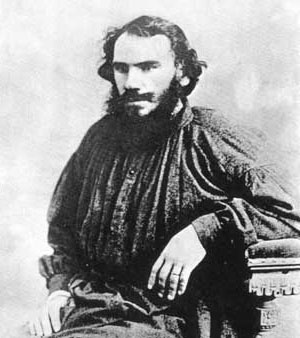

Sometims an odd experience or an unexpected relationship changes a person's life. A pig changed mine. So did a long-dead Indian poet named Rabindranath Tagore.  Leo Tolstoy was born at Yasnaya Polyana ("Sunny Meadows"), the large ancestral estate of a wealthy aristocratic family, the fourth of five children. Orphaned at the age of nine, he was reared by his aunts.

Leo Tolstoy was born at Yasnaya Polyana ("Sunny Meadows"), the large ancestral estate of a wealthy aristocratic family, the fourth of five children. Orphaned at the age of nine, he was reared by his aunts. After a period of travel he settled down on his estate, and started a school for the children of the peasants. At age 34 he married the teenaged Sofia Bers; in the course of their 48-year marriage the had thirteen children, eight of whom survived to adulthood. The early years of the marriage were happy and liberating to Tolstoy. Sofia strongly supported him in the writing of his two great novels, Anna Karenina and War and Peace, copying out his many drafts day after day. Quickly the two novels were (and still are) acclaimed as among the greatest works of Russian literature.

After a period of travel he settled down on his estate, and started a school for the children of the peasants. At age 34 he married the teenaged Sofia Bers; in the course of their 48-year marriage the had thirteen children, eight of whom survived to adulthood. The early years of the marriage were happy and liberating to Tolstoy. Sofia strongly supported him in the writing of his two great novels, Anna Karenina and War and Peace, copying out his many drafts day after day. Quickly the two novels were (and still are) acclaimed as among the greatest works of Russian literature.