The Peaceable Kingdom

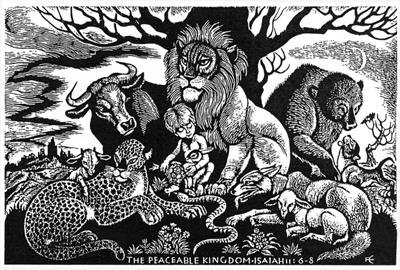

The familiar image of a child surrounded by animals is based on the extraordinary lines in Isaiah 11:6-8: "The wolf shall live with the lamb, and the leopard will lie down with the kid, the calf and the lion cub feed together, and a little child shall lead them. The cow and the bear will graze, their young will lie down together; the lion will eat hay like the ox. The nursing child will play by the hole of the cobra. . . . They will not hurt or destroy in all my holy mountain. . ." No lion and lamb together, actually, but the familiar image makes a good shorthand for the passage.

This beautiful image has much in common with the Christmas narrative in Luke of the baby in the manger, glowing with divine light. (No mention of animals in the scene, actually, but undoubtedly they do belong there.) Both passages suggest that beings whom adults have routinely considered beneath them, or even expendable--the homeless, the infant, the beasts--hold the secret of ultimate transformation and peace.

The Peaceable Kingdom has been painted many times. One of the most deeply affecting is the above drawing by Fritz Eichenberg. Unlike the tamed beasts in most other versions, the faces of Eichenberg's animals are deeply ambivalent: is that a look of sorrow, or of deep reflectiveness, or of predatory fire in this or that animal? The lamb trusts the wolf, and the wolf accepts the lamb's companionship, but the wolf is still clearly a wild beast. The bull's horns are very sharp; the bear is massive and threatening; yet all are drawn to the Child, and accept being part of his or her court. There are other ambiguities: is it winter or spring? night or day? Is that pollution above the city, or just clouds in a night sky? If truth is going to break in with its matter-of-fact--how can small child, without caretaker, live out in the wild far from the human community?

In the midst of these miracles and potential dangers, the Child holds a bouquet of flowers and caresses the rabbit with perfect serenity. One might reply that the key, of course, is that the Child is the offspring both of humanity and of the Divine. In traditional Christian language, he is Jesus, the one incarnation of God who reunites humanity with God by his birth among us and by his transcendence of human limitations, especially death. In Vedantan language the Child may be said to represent the Transcendent Self. The Child is unafraid because s/he is so deeply akin to the beasts as to be at home with them, and cannot be destroyed by even the worst that the predators (or the denizens of the city) can do.

"Be born is us today" echoes the Quaker affirmation that there is That of God in each of us, waiting to be born. It is not enough simply to know that the Child is within each of us. We must labor to give him birth, to nurse and nurture her until we become united to this Divinity in every part of our lives. This unlimited compassion, this innocent fearless delight, is to be realized in our day-by-day consciousness and actions. This process is lifelong (or requires many lives) for the vast majority of us. It takes courage, patience, humility and true self-love as we give ourselves, over and over again, to be channels of the Divine Peace.

Let us take the adventure that is sent to us!

Although Judy Carman is keenly aware of the egregious cruelties inflicted

on animals every day, and describes them, Peace to All Beings resonates

with hope. Just as the negative energy that we human beings put forth into

the universe has harmful effects, Carman explains, affirmative thinking and

prayer contribute substantively to the healing of the world. In addition to

expressing the need for hope and positive thinking, the author laces her

work with inspiring stories of animals rescuing humans and other animals.

The book also includes a substantial number of pro-animal quotations by

various famous people. I found this collection of inspiring stories and

quotations to be one of the greatest strengths of the book: Some of them are

familiar, but it is helpful to have them all together in one source.

Although Judy Carman is keenly aware of the egregious cruelties inflicted

on animals every day, and describes them, Peace to All Beings resonates

with hope. Just as the negative energy that we human beings put forth into

the universe has harmful effects, Carman explains, affirmative thinking and

prayer contribute substantively to the healing of the world. In addition to

expressing the need for hope and positive thinking, the author laces her

work with inspiring stories of animals rescuing humans and other animals.

The book also includes a substantial number of pro-animal quotations by

various famous people. I found this collection of inspiring stories and

quotations to be one of the greatest strengths of the book: Some of them are

familiar, but it is helpful to have them all together in one source. I made the decision to go vegetarian in 1974, while living in an Israeli

kibbutz, as a result of seeing the film The Death of Trotsky. The movie

included very graphic footage of a Mexican bullfight--a misleading term,

since the toro is not really fought, but baited and killed--and the

subsequent butchering of the poor animal's corpse. One would have to be

quite stonyhearted to watch this and not give up beef for life.

I made the decision to go vegetarian in 1974, while living in an Israeli

kibbutz, as a result of seeing the film The Death of Trotsky. The movie

included very graphic footage of a Mexican bullfight--a misleading term,

since the toro is not really fought, but baited and killed--and the

subsequent butchering of the poor animal's corpse. One would have to be

quite stonyhearted to watch this and not give up beef for life.

Loving looks the large-eyed cow,

Loving looks the large-eyed cow,

Little Lamb, who made thee?

Little Lamb, who made thee? If people were like horses,

If people were like horses,