God'

s Dream for Animals:

Process Theology and Animal Ethics

Process Theology and Animal Ethics

Fay-Ellen Ellwood and a friend

Why are we here? "What's it all about?"

Any attempt to see the world as a reality that is not merely physical but also purposeful and spiritual—a perspective that includes God—must also speak to the issue of the place of animals. For many centuries, when Christians have tried to understand God's plan for the world, they have nearly always considered human beings as the only players of real value in the story, overlooking God's plan for animals or holding it as secondary, at best, to God's plan for humanity. We do not argue that the possible role of animals is greater than, or even equal to, that of humans, only that in focussing solely on humanity we do ourselves as well as animals a disservice. According to process thinker Alfred North Whitehead, one of the problems with religion is that it is often expressed in terms of ancient or expired human experiences: "Religion will not regain its old power until it can face change in the same spirit as does science. Its principles may be eternal, but the expression of those principles requires continual development."

If we agree that animals have feelings, and indeed souls as Whitehead believed, to dismiss animal suffering as a result of their being part of the "circle of life" is not adequate, any more than it would be to justify human suffering in such a way. Neither does it seem responsible to justify animal suffering with, say, traditional Biblical explanations such as God's giving Adam "dominion" over the creatures, while taking a more progressive understanding of the suffering of humanity as a wrong we should seek to right.

What does it mean for animals to say that "God so loved the world"? We think of God as an all-loving being who works in partnership with the world. As God is the God of the whole world, S/He is also the God of the dog or cat we share our lives with, the bald eagle, and the opossum rummaging through our garbage can. When we take a moment to observe animals with an open mind, it is quite easy to see that they are capable of suffering and joy, and have aims and fears.

As there exists "that of God" in every one, we feel that God loves unconditionally, with compassion for both the oppressed and the oppressor. A God that is everywhere present is present to the consciousness of every creature. If we do to God whatever we do to "the least of these," then God shares the pleasures of every creature, and feels compassion for every creature that experiences need, oppression and violence. This would not make much sense if we could not bear witness to the reality of animal happiness or suffering. We may not always be precisely correct in our interpretations of what they feel, but overall the picture is clear enough. For example, our family's ginger tabby cat Isaac purrs and settles down on a lap when petted, and yelps and runs away if one accidentally steps on his tail. If we do not reduce such reactions to unfeeling mechanical responses in our beloved family companion animals, neither should we assume that is the case with cows or chickens.

It is fairly easy to understand the basics of the way in which the God of process theology loves and values animals. But to what degree are we obligated to act upon the ethical implications of these principles? This is the rub. Many Christians—many Friends—are reluctant to adopt lifestyles in which they consciously reduce the suffering of animal life, such as the elementary step of being vegetarian. Friends are for the most part comfortable with the place where most people in our western society draw the line of sympathy. This position is understandable; we work so hard for good and for justice in other areas of our lives, that we may feel if we take on one more cause we may very well exhaust ourselves.

One partial answer to this stance is that this may be more a matter of immediate emotional reaction than of a crucial decision about ongoing investment of time and energy. Not everyone is called to be active in working on behalf of animals; it may be merely a matter of ceasing to cause them unnecessary harm. After a very limited time spent developing vegetarian menus, one may continue as before to labor on the concerns to which one already feels drawn.

But it is a fact that for the most part, meeting human needs involves some injury to some part of God's creation, and it is not obvious to every person of good will just where the line between necessary and unnecessary harm should be drawn. In order to make land available to raise nonbloody food—broccoli, say, or grapes, or soy—the habitats of many wild animals were destroyed, and the animals lost their lives. Whole species may have been wiped out. If it is impossible for vast numbers of people to be fed without animals being killed thus, some may feel that it is quibbling to object to killing cows or chickens for us to eat.

It is true that vegetarians cannot wash their hands in innocence while pointing accusingly at the guilty meat-eaters, and in any case such self-righteousness makes for an ugly spectacle. We must face the fact that, willingly or not, we are all involved in the deaths of others in order that we may live and thrive. Then why not go ahead and eat our steak? Isn't it simply part of the package of life arising out of death?

To affirm that it is would be like saying "I am in blood / Stepp'd in so far that, should I wade no more, / Returning were as tedious as go o'er" —but this stance is no more valid for us than it was for Macbeth. It is mere rationalization meant to justify the self-indulgence of questionable desires. We can stop short in the river of blood; we can do as little violence as possible. We can opt for soy instead of steak.

Some process thinkers image God as being the Soul of the world, and the world as God's body, who feels the pains and pleasures of every being, rather as a human psyche does those of every tissue and organ. One problem that arises out of this concept is that such a God shares not only the pain of the victim but the gratification of the predator. Not only does God share in the fear and anguish of, say, a gray whale hunted by orcas, God also feels the satisfaction the orca takes in eating the flesh of a freshly killed whale. It seems likely then that God experiences a deep tension between tragedy and beauty, between desire and pain. But if S/He shares in all the conflicting aims of different creatures and that is just the way things are, how can we claim that the nonviolent vegan diet is the will of God? God suffers the pain and frustration of the chicken who lives a miserable life pent up in a tiny cage, and the horror of being killed, but perhaps God also shares in the enjoyment of the diner eating a savory herb-seasoned chicken dish.

But what is different between God's experience and that of the human meat-eater may be that while sharing in her or his brief enjoyment of eating the flesh, God is also aware of what the diner is probably screening out—that there was a conscious being suffering protracted misery before being violently turned into a thing on a platter. Then God must also have a sense of the disproportion between these two aspects of the situation. When we factor in the harmful long-term effects on humans of a meat-centered diet—the pain of a young mother dying from breast cancer, of a father suddenly felled by a heart attack—then go on to the grief of families and friends suffering at their losses, it is clear how costly to God is the pleasure of those dishes. Nor would God be oblivious to the destructive effects of our huge factory farms and slaughterhouses on other animals, plants, people, on the earth itself—water depletion, toxic pollution, desertification, global warming, extinctions. God's pain is exponentially increased with every further dimension that is opened up.

Why, then, would God, who is so deeply enmeshed in our world as to be called the Soul of the world, be involved in something that seems so wrong? Clearly the whole animal agribusiness system is not simply "the way things are." A product of greed, technologies and out-of-control human population growth, this system is not even the Circle of Life; it is a wild, open spiral containing vastly and increasingly more death than life. It is a humanly-created monstrosity that humans can opt to change.

Process theologies see not a particular Way Things Are but a dynamic situation in which God's Dream of a world of complexity, intense experience, beauty, love, and enjoyment is caught, however, dimly, by finite consciousnesses who are themselves developing. Complexity and intensity of experience entail a potential for pain, which is the cost God and finite creatures pay, but it is not at the heart of the Dream. God is not dominating or violent; God does not coerce creatures into realizing the Dream, but lures and inspires us to take up the adventure of co-creating.

The author of Proverbs says "Better is a dinner of vegetables where love is, than a fatted ox and hatred with it" (Prov. 15:17)—better for the health of the humans, and surely better for the health of the ox. A Peaceable Table holding a feast of plant food seems much closer to realizing a little of God's Dream of enjoyment for all than one containing severed pieces of animal bodies.

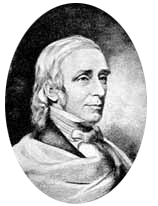

Amos Bronson Alcox was born on a flax farm in Connecticut in 1799. He attended an ill-equipped, primitive schoolhouse where a library was unheard-of and the rod was freely applied. He taught himself to read and write in part by forming letters in charcoal on the wooden floor. To further their education, he and a cousin wrote journals on paper scraps they stitched together, and critiqued each other's work; they scoured the nearby farms looking for books to borrow, finding a few gems such as Pilgrim's Progress. His formal schooling ended at 13.

Amos Bronson Alcox was born on a flax farm in Connecticut in 1799. He attended an ill-equipped, primitive schoolhouse where a library was unheard-of and the rod was freely applied. He taught himself to read and write in part by forming letters in charcoal on the wooden floor. To further their education, he and a cousin wrote journals on paper scraps they stitched together, and critiqued each other's work; they scoured the nearby farms looking for books to borrow, finding a few gems such as Pilgrim's Progress. His formal schooling ended at 13. Bronson's commitment to compassion and justice led him into vegetarianism in his early thirties. Together with his colleague and financial backer Charles Lane and others, in 1843 he set up a community called Fruitlands that was to use no products of human or animal slavery. The down-to-earth Abigail was dubious about these innovations, but was willing to give them a try. It might have worked had Bronson and Lane added to their idealism a large dollop of common sense, but Louisa May's later image of her philosopher-father as living up in the sky with his family trying to pull him to earth by a rope had too much truth to it. Bronson and Lane were quite willing to do hard manual labor, but at other times would hold profound conversations while urgent farming tasks waited, or go off to recruit other members when a storm threatened the harvest. Their linen garments, designed by the ascetic Lane, had an outre appearance that called down derision on them and hindered their attempts to communicate. As winter came down their finances failed, their provisions dwindled, and in January, 1844 the community collapsed. The farm was bought by one of the supporters, who eventually made it both a prospering business and an open-door soup kitchen for the poor of the area. Today it is a museum.

Bronson's commitment to compassion and justice led him into vegetarianism in his early thirties. Together with his colleague and financial backer Charles Lane and others, in 1843 he set up a community called Fruitlands that was to use no products of human or animal slavery. The down-to-earth Abigail was dubious about these innovations, but was willing to give them a try. It might have worked had Bronson and Lane added to their idealism a large dollop of common sense, but Louisa May's later image of her philosopher-father as living up in the sky with his family trying to pull him to earth by a rope had too much truth to it. Bronson and Lane were quite willing to do hard manual labor, but at other times would hold profound conversations while urgent farming tasks waited, or go off to recruit other members when a storm threatened the harvest. Their linen garments, designed by the ascetic Lane, had an outre appearance that called down derision on them and hindered their attempts to communicate. As winter came down their finances failed, their provisions dwindled, and in January, 1844 the community collapsed. The farm was bought by one of the supporters, who eventually made it both a prospering business and an open-door soup kitchen for the poor of the area. Today it is a museum.