God Has Given Them Joy

Photo by Jim Brandenburg

Photo by Jim Brandenburg

The well-known farewell speech of Father Zossima in Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov includes a passage in which the saint says "Love the animals: God has given them the rudiments of thought and joy untroubled. Do not trouble it, don't harass them, don't deprive them of their happiness, don't work against God's intent."

Although most of Zossima's speech seemed to me full of deep spiritual wisdom, this passage always gave me pause. I certainly agreed that we should not abuse animals, but even in nature, there is endless violence and pain in the animal world. In addition, vast human crimes against them seem to make for an ocean of darkness and anguish in which our precious animal kin were drowning. How could the wise Zossima have said that God has given them the rudiments of joy untroubled?

One cannot deny or minimize the suffering that results from predation, parasitism, exposure, and unfulfilled need among animals (and in fact this suffering in nature presents an extremely grave problem for theodicy). But it is a serious error to see violence and suffering as virtually the whole picture. I was unaware of the extent to which my view of the situation was informed by the effects of the Darwinian focus on natural selection as the central principle of evolution (together with other influences such as the theology of the Fall). "Nature is red in tooth and claw," goes the saying, which seems only too obvious. "Life feeds on life." Together with this outlook usually goes the conviction that "one can't fight it."

It is the "one can't fight it" stance which feeds and justifies human violence against animals. Spokespersons for animal agribusiness, responding to activists' charges of cruelty against animals, point out that their charges are fed and housed against cold weather and predators, security that they cannot expect in nature; "They get their next meal, which is all they care about," is a typical defense. If the situation of animals in nature is nothing but deprivation, violence and misery, human treatment of them in factory farms is merely a carrying on of the inevitable, or even an improvement over nature, and one can hardly find fault.

There are at least two problems here. One is a disturbing parallel to some of the early defenses of human slavery offered in reply to the charges of abolitionists. The plight of these people in darkest Africa, it was said, is even worse than their situation here: oppression, witchcraft terrors, rampant wars, horrors unimaginable. While there may be unpleasantness in their lot here, they have assurance of food and housing (and the immeasurable privilege of being exposed to Christianity). As to the obvious pains of servitude, the lash, and family separations brought about by the slave trade, with some inconsistency it was claimed that "the negro" was an animal-like creature who would go amok without the control of his betters. Furthermore, he lacked the sensitive feelings of white people; with a plate of food, and a holiday bottle of liquor, he would soon forget his troubles. (See Marjorie Spiegel, The Dreaded Comparison: Human and Animal Slavery) Obviously, the choices to see violence as the heart of animal life, and animals as having only the most primitive feelings, are equally suspect.

The central problem in the "one can't fight it" outlook is that the life of animals in the wild is no more an unrelieved nightmare than was that of Africans in their own countries. Animals do have joys. Wise observers such as Father Zossima and the narrator of "The Windhover" (see the poetry section) have long known this. In The Pleasurable Kingdom (reviewed below), ethologist Jonathan Balcombe presents and supports this truth, describing many pleasures that animals enjoy, including food, companionship, attachment, touch, and the gratification of doing something one is good at. It becomes abundantly clear that by enslaving, tormenting and killing our animal kin, factory farmers and their millions of beneficiaries have indeed, in Dostoevsky's terms, deprived animals of their happiness, and worked against God's intent. But those who treat animals with respect and kindness, and encourage others to do the same, are, to whatever small degree, furthering the realization of that intent in the Peaceable Kingdom.

—Gracia Fay Ellwood

We invite responses to editorials or any other feature of PT for our next issue's letter column: graciafay@mac.com.

This is a revolutionary book about what ought to be taken for granted: that nonhuman animals not only feel pain, but play, seek pleasure, and enjoy good sensations as intensely as we humans do. To be sure, some observant humans might acknowledge that "higher" mammals closely associated with them, their dogs, cats, horses, and perhaps a few others, seem to appreciate being stroked or taken for walks. It would probably be recognized that many species may have powerful sex drives, the fulfillment of which apparently brings satisfaction as well as reproduction. But beyond that, most of us may fall back on the familiar stimulus-response model, essentially holding that while animals act to avoid pain, positive pleasure is something reserved for the dominant species and those to whom its lords deign to give it.

This is a revolutionary book about what ought to be taken for granted: that nonhuman animals not only feel pain, but play, seek pleasure, and enjoy good sensations as intensely as we humans do. To be sure, some observant humans might acknowledge that "higher" mammals closely associated with them, their dogs, cats, horses, and perhaps a few others, seem to appreciate being stroked or taken for walks. It would probably be recognized that many species may have powerful sex drives, the fulfillment of which apparently brings satisfaction as well as reproduction. But beyond that, most of us may fall back on the familiar stimulus-response model, essentially holding that while animals act to avoid pain, positive pleasure is something reserved for the dominant species and those to whom its lords deign to give it.

This film, a sequel to Ice Age, would in the old days have made an excellent double feature with An Inconvenient Truth (see review below). Both films deal with global warming and catastrophic climate change. In this movie a community of Pleistocene animals finds itself seriously threatened with drowning by the imminent melting of the huge glaciers that surround their happy valley. The animals do not always get along, and whether they will be able to stay together as a family is very much in doubt.

This film, a sequel to Ice Age, would in the old days have made an excellent double feature with An Inconvenient Truth (see review below). Both films deal with global warming and catastrophic climate change. In this movie a community of Pleistocene animals finds itself seriously threatened with drowning by the imminent melting of the huge glaciers that surround their happy valley. The animals do not always get along, and whether they will be able to stay together as a family is very much in doubt.  How real--and how imminent--is global warming? Of a total of 928 articles in serious scientific journals, 928 conclude that it is a real and serious problem, largely caused by unwise human activities. None cast doubt on these conclusions. The numbers are very different when we move from the scientific to the popular press: there, 53% of the articles surveyed express some doubt of the problem's existence or human causality. This is because over 50% of the popular press, like over 50% of the U.S. Senate, is controlled by conservative, largely anti-environmentalist, forces.

How real--and how imminent--is global warming? Of a total of 928 articles in serious scientific journals, 928 conclude that it is a real and serious problem, largely caused by unwise human activities. None cast doubt on these conclusions. The numbers are very different when we move from the scientific to the popular press: there, 53% of the articles surveyed express some doubt of the problem's existence or human causality. This is because over 50% of the popular press, like over 50% of the U.S. Senate, is controlled by conservative, largely anti-environmentalist, forces.

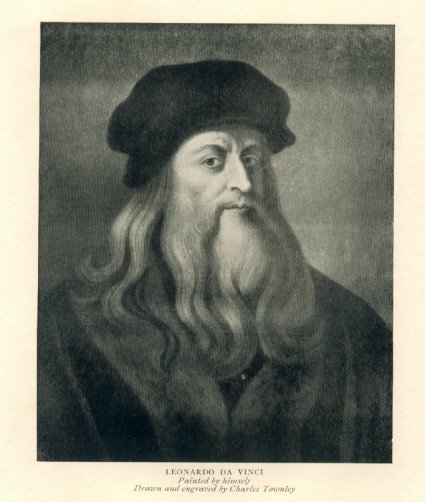

Leonardo da Vinci, the Renaissance man par excellence, is well known for his many works of genius in the fields of painting, draftsmanship, scientific discovery, invention, and music, among other things. However, most do not know that he was also a sensitive and committed vegetarian, and perhaps vegan. An independent witness to his practice comes from a letter by one Andrea Corsali to Leonardo's patron Giuliano de' Medici: "Certain infidels called Guzzarati [people of Gujarat, the same region of India from which Gandhi came] do not feed upon anything that contains blood, nor do they permit among them any injury be done to any living thing, like our Leonardo da Vinci."

Leonardo da Vinci, the Renaissance man par excellence, is well known for his many works of genius in the fields of painting, draftsmanship, scientific discovery, invention, and music, among other things. However, most do not know that he was also a sensitive and committed vegetarian, and perhaps vegan. An independent witness to his practice comes from a letter by one Andrea Corsali to Leonardo's patron Giuliano de' Medici: "Certain infidels called Guzzarati [people of Gujarat, the same region of India from which Gandhi came] do not feed upon anything that contains blood, nor do they permit among them any injury be done to any living thing, like our Leonardo da Vinci."