Editorial: Quakers and Abolition

The history of Friends’ struggle to end the cultural evil of human slavery has become a major model for present-day Quakers laboring under an animal Concern.

Minutes and Evasions

Following scattered individual denunciations, the movement among Friends began officially in 1688 with a minute totally condemning slavery, especially the slave trade, proposed by four Germantown Friends to their Monthly Meeting in Dublin, Pennsylvania. The minute (or rather the buck) was passed on first to Quarterly and then to Pennsylvania Yearly Meeting (the umbrella gathering), and was finally dismissed by the latter with suitably evasive words.

The shameful fact is that, despite the Inner Light and the testimony of Equality, Quakers were themselves complicit in various aspects of human slavery, which was to result in painful intra-Society conflict. It is instructive that six years after the ignoble spectacle of 1688, a considerably more limited minute, urging Quaker merchants to discourage their contacts abroad from sending slaves, was passed by Pennsylvania Yearly Meeting.

Furthermore, not all Friends involved in slavery resisted the abolitionist movement, as can be seen by the fact that between 1675 and 1710, many Maryland Friends freed their slaves. Some Friends felt it best to keep or even buy slaves in order to insure that they would receive humane treatment and an education, but others seemed to find little problem with professing Equality and profiting from their human property.

In 1727, with the support of concerned North American Friends, a minute censuring the slave trade was passed by London Yearly Meeting (LYM). A generation later, in 1758, it was necessary for LYM to condemn the slave-trade again, and urge Friends everywhere to stay clear of “this unrighteous gain of oppression.” The point was made yet again in a minute in 1761, this time including a clause that disowned any Friend who persisted.

Abolition and Compassion

Finally, under the continued influence of concerned North American Friends, principally John Woolman, London Yearly Meeting passed a minute in 1772 calling for all slavery to be “utterly abolished.” In the next two decades slavery among Quakers did disappear, with the help of economic conditions. The whole process took about a hundred years. (See the online site “Quakers in Britain.”)

The quality of the decades-long labors of Woolman and his colleagues Joshua Evans, Anthony Benezet, and other compassionate and far-sighted Friends are important to the eventual success of the abolitionist movement within the Society. Woolman was passionately and doggedly devoted to the cause, much given to prayer, and willing to follow the leadings of Divine Love, whatever the cost in social awkwardness or the sacrifice of comforts. During long journeys on foot in the 1750s and 1760s to speak to various Meetings and individual slaveholders, he and his companions combined an unsparing prophetic critique of slavery with a loving concern for the slaveholding Friends they addressed. They spoke with gentle tact, and worked with their hearers to deal the often formidable logistical problems involved, which included the danger of unemployment and starvation for the liberated persons. Woolman’s ministry remains a cherished model of Light answering Light.

Reaching Out

In the late 1700s, Friends, especially in Britain, were also taking action toward ending all human slavery in the English-speaking world. This involved inventing new tools: the boycott, the public petition, and the lobby. In the 1780s Friends formed the first anti-slavery society, and soon joined with Anglican and Evangelical abolitionists in writing essays for newspapers, printing and distributing eye-opening flyers and booklets, promoting boycotts of slave-produced sugar, gathering signatures on a petition to Parliament, and lobbying parliamentarians, especially William Wilberforce. These efforts achieved a major breakthrough in Parliament’s abolition of the slave trade in 1807, and culminated in 1833 in the abolition of slavery in English domains (See PT, April, '07).

Also in the late eighteenth century and increasingly in the nineteenth, some devoted US abolitionist Friends turned to civil disobedience: specifically, the Underground Railroad, They not only risked opprobrium, legal action, imprisonment, and assassination, their work was sometimes resisted by other Friends who spoke against them and denied them the use of Meetinghouses for strategy sessions. Notable heroes of this work were “stationmasters” Levi Coffin and Catherine Coffin of Newport, Indiana; Thomas Garrett of Wilmington, Delaware, who lost his hardware store to a $5,000 fine, but rebuilt and continued his work; and prophetic preacher  Lucretia Coffin Mott (pictured) and James Mott of Philadelphia. (Impressive though the work of these and other brave Friends may be, it should never be forgotten that the self-liberated persons themselves, facing death by torture, risked infinitely more.) . . . .

Lucretia Coffin Mott (pictured) and James Mott of Philadelphia. (Impressive though the work of these and other brave Friends may be, it should never be forgotten that the self-liberated persons themselves, facing death by torture, risked infinitely more.) . . . .

"And the Moral of That"--

Some practical insights helpful to faith-based animal defenders may be gleaned from the history of Quaker

abolitionism. Conspicuous is the need to to give much time to prayer; to be prepared for resistance, perhaps hostility, from members of one’s spiritual family, but to continue, as best one can, to channel divine love to them; and to be committed to the long haul. There will be a time for compromise, and a time for civil disobedience to rescue victims; there is a time for new vision that finds new ways and means. Needed at all times are steadfastness, courage, and compassionate love for both oppressors and victims. The best of us fall short at times, but now is never the time to quit.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

Excerpted from "Animals, Prophets, and the Hidden Paradise,"

in Religious Reflections on Animal Advocacy,

edited by Anthony Nocella II, to be published by LanternBooks.

News Notes

Eat This!

This short, non-graphic cartoon video exposes the negative effects, ranging from environmental degradation to world hunger, of raising animals for food,. It encourages the audience to be mindful of what we eat, and to give plant-based foods a chance. It would be effective with children. To view the video please visit www.eatthis.org.uk/veg_anim.html

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

Christian Vegetarian Association www.christianveg.com

More Leg Room for Laying Hens

Thanks to a small (and easy!) campaign run by some members of Quaker Concern for Animals and local Green Party members, eggs from battery hens will be banned from dozens of schools, care homes, and canteens in the county of Merseyside, England.

The borough council of Wirral, near Liverpool, has become the third in Britain to become eligible for a "Good Egg Award" from Compassion in World Farming. The council leader backed the idea, citing TV campaigns which highlighted the issue. The local Channel 4 screened four programmes in one week by prominent chefs, proving beyond all doubt that hens kept in batteries (and also "broilers" produced for meat) live miserable lives. The new system will allow for a little more natural behavior. However, the male chicks are still killed at birth, and free range hens are seized, transported, and slaughtered in exactly the same way as those from batteries. Both are appalling processes.

Despite those caveats, we are hoping that this decision will send out an important message to the public and heighten their awareness about the existence we impose on sentient beings in the perpetual search for cheap food. We are also hoping that other campaigners will approach their city councils and achieve the same result.

--Contributed by Marian Hussenbux

Quaker Concern for Animals

quaker-animals.org.uk

Book Review: The World Without Us

The World Without Us by Alan Weisman. NY: St. Martin's Press, 2007.

Hardcover, $24.95. 324 pages.

Alan Weisman, an award-winning international journalist, investigates in this book the question of what would happen on earth if the entire human race were to vanish--whether by a universal Rapture, an alien abduction, or a powerful virus.

Alan Weisman, an award-winning international journalist, investigates in this book the question of what would happen on earth if the entire human race were to vanish--whether by a universal Rapture, an alien abduction, or a powerful virus.

Weisman describes a scenario in which, within days, the failure of pumps would lead to flooding of New York subways; later, streets would crack and crumble, while vines and other plant life would overtake houses and tall buildings (as they have in ground-zero Chernobyl in only twenty years). Copper pipes would collapse to mere seams, whereas bronze items might last for thousands of years. Chemically poisoned fields, near-extinct fish species, and moonscaped ocean floors would restore themselves to their pre-human vitality. One of the near-permanent "gifts" of humanity to earth would, unhappily, be plastic debris.

The posited human die-off may not be so farfetched, at least in large areas; in east Africa the AIDS epidemic threatens to reduce the population to a small remnant. This might be seen as very bad cultural (not individual) karma, since human HIV is apparently the result of humans consuming the flesh of chimpanzees, our close relatives (pages 85-87). Paradoxically, this agonizing human tragedy would be a blessing for wild animals such as African elephants and apes, who are in grave danger of becoming extinct unless we do so first--or, better, find a way to curb our destructiveness.

On page 36 the author speculates that rats will become extinct without human-generated garbage. This is unlikely; rats are adaptable, clever, and omnivorous. Weisman may have changed his mind about this prediction; in the excellent film made from this book, Life After People, the outcome for rats is more hopeful. It posits that after our garbage heaps and stale food in supermarkets have been used up, rats will find their own ecological niche. The author also anticipates the probable extinction of dogs without human protection from major predators. This, too, is unlikely (except for vulnerable human-created breeds). True, a single dog is no match for a cougar or grizzly bear, but dogs are pack--or rather community--animals, whose strength is in their numbers. United, they will survive.

While such prospects as the death from hunger and thirst of shut-up animals is painful to contemplate, as is the probable drying-up of many Canadian lakes and the destruction of libraries and other cultural treasuries, it is partly because of such glimpses of doomsday that this book is to be recommended (in spite of some errors of fact and unlikely predictions). The book constitutes a strong warning about the way humans are destroying the planet, yet it gives hope from Earth's re-greening power.

Weisman did not write this book for its entertainment value alone, nor as a mere thought-experiment. He wanted readers to think " . . . if nature could do all that, then is there a way that this renewal could happen that does not depend on our extinction? Weisman's suggested solution is limiting our birthrate to one child per family. While not ruling out other solutions, we at the Peaceable Table propose: a vegan diet for all, and an open heart to the spiritual dimension of life.

--Benjamin Urrutia

Benjamin is interested in communicating with vegans who like to discuss the music of Mozart, as well as the animal themes (and other aspects) of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and J.K. Rowling. His e-address is chikuku52@yahoo.com .

Film Review: The Water Horse

The Water Horse: a film directed by Jay Russell, written by Robert Nelson Jacobs, based on the novel by Dick King-Smith (creator of Babe). Starring Alex Etel as Angus MacMorrow, Emily Watson as his mother Anne MacMorrow, Pritanka Xi as his sister Kirstie McMorrow, Ben Chaplin as Lewis Mowbray the handyman, David Morrissey as Captain Hamilton. 2007.

The film starts in the present (the early 21st century), when tourists enquire about the "Loch Ness Monster" and the famous photograph thereof. We soon get the facts: The picture is a total fake (indeed, we see how it was faked), and there is no Monster. No Monster at all - but a gentle creature, as much a part of God's creation as you or me or any animal. The animal in question is apparently a Plesiosaur. Plesiosaurs, King-Smith theorizes, have managed to survive by adopting a strategy of laying a single egg, which is fostered by humans. This has been going on for ages, and legends abound about the Selkie or Water Horse.

In 1942, an egg is found by a wee lad named Angus, who is played by a talented child actor named Alex Etel. He has brown hair above a high pale forehead and a sensitive face. (He looks so much like me at that age that looking at him is very much like gazing at a magic mirror that removes half a century and adds a smattering of freckles.) The intelligent but sad and lonely boy is living in a state of denial: His father's ship was sunk in the war a year ago, but Angus insists that he will return, alive and well and triumphant. Soon he goes from being a fatherless child to being father and mother to a small creature with a huge appetite: Angus has found the Selkie egg, and the fate of the species is in his hands. The war, however, may make the line of the Water Horse extinct.

Things are complicated by a major testosterone clash between Captain Hamilton, who is billeted in the chateau whereof Angus' mother is the housekeeper, and Mr. Mowbray the handyman. The two men detest each other. The captain suspects Mowbray of being a deserter, a shirker, or worse. (He is not: Mowbray is an injured war veteran and hero.) Mowbray thinks the Captain is an arrogant Sassenach. This is wrong also; Hamilton is a decent fellow, if a bit misguided.

But yes, there is a villain in the story: a soldier with a cruel face who loves to hunt. We see him with one of his victims, a stag whom he has enjoyed destroying. When this bloodthirsty man learns there is a big animal swimming in the Loch, he declares war on the poor beast. The movie makes the point powerfully that there is no difference between war and hunting; they are both wanton killing.

British artillery and machine guns threaten the extinction of one of the world's most ancient animals. I am not going to spoil the story by telling the outcome, but I guarantee that you will find this one of the most engaging and beautiful movies you have ever seen. It also communicates on a visceral level how wrong it is for humankind to wreak violence upon God's creatures.

--Benjamin Urrutia

Recipes

Hearts of Palm Salad

Serves 4

1 can or jar of hearts of palm, cut into chunks (about ¾ inch thick)

1 cup frozen peas

½ small red onion, chopped

¼ cups black olives, pitted and chopped (Gaeta or Niçoise are very good)

½ sweet red bell pepper, chopped

1 small carrot, grated

2 tsp. Dijon mustard

1 clove garlic, minced

½ tsp. thyme, dried and crumbled

¼ cup olive oil

1 T. vegenaise or nayonaise

2 T. red wine vinegar

1 tsp. fresh lemon juice

2 tsp. spring water

½ tsp. sea salt, or to taste

freshly ground black pepper, to taste

In small bowl, whisk together dressing ingredients. Toss

with other ingredients in a medium-size salad serving bowl. Allow to sit

at room temperature so that the peas fully thaw. The salad may be

refrigerated until ready to serve once peas are thawed. Serve over a bed

of greens with a rustic bread.

-- Angela Suarez

Red Lentil & Arborio Rice Stew

Serves 6

1 small yellow onion, chopped

1 small yellow onion, chopped

2 small – medium carrots, chopped

¼ cup extra virgin olive oil

2 T. tomato paste

1 T. red curry paste

1 T. unbleached flour

1 tsp. coriander powder

½ tsp. chili powder

⅛ tsp. (or less, to taste) ground cloves

½ lb. red lentils, well rinsed

¾ cup arborio rice

½ lb. frozen edamame (shelled)

½ lb. frozen yellow corn

½ - ¾ tsp. sea salt, or to taste

1 can light coconut milk

8 cups warmed spring water mixed with 1 T. vegetarian broth powder

In large soup pot, sauté onions and carrots in olive oil until onion becomes transparent. With a wooden spoon, stir in tomato paste, curry paste and flour. Stir well to blend. Add just a little warm spring water to prevent clumping (about ¼ - ⅓ cup); then add the coriander, chili powder and cloves – stir with wooden spoon to blend. Add lentils, rice, edamame and corn along with the coconut milk, spring water and salt. Bring to boil; reduce heat and let simmer for 20 -25 minutes until rice is tender. Serve in soup bowls on a cold winter day.

-- Angela Suarez

Injera – Angela’s Variation

Makes about 10 -12 pieces of injera skillet bread

½ cup teff

1 ½ cups unbleached flour

1 T. extra virgin olive oil

½ tsp. sea salt

2 cups spring water

In a blender, grind teff to make a flour. Pour teff flour into a medium size mixing bowl; add the unbleached flour, olive oil, salt and water. Whisk well until very smooth. Cover and allow to sit for at least 20 minutes.

To bake, heat an electric skillet to 350° F, spray with non–stick cooking spray. Spoon about 3 T. batter onto the hot skillet; tilt skillet in turning motion to spread the batter into a circle, so that it is crêpe-like. Bake on one side for about 2 – 3 minutes; flip over with a spatula and bake the other side for about 1 – 2 minutes. Remove from skillet and stack. Repeat this process until the batter is all used.

Injera is an Ethiopian flat bread. I enjoyed it once with a delicious vegan Ethiopian meal at a restaurant in Pittsburgh named Abay. The bread was delicious and I was able to find an authentic recipe by an Internet search. With a couple of minor alterations, this is how I make my style of injera.

-- Angela Suarez

My Pilgrimage: Making Connections

By Sola Wolf

Sola Wolff with Mule Mare Friend Umber

Sola Wolff with Mule Mare Friend Umber

I love animals. I always have. I remember spending hours at a time watching all kinds of animals, fascinated with their movement, their habits, their interactions with each other and with me, and trying to figure out their languages so that I could communicate with them. If I could have chosen a super-hero power, I would have happily passed by the ability to fly for being able to hear and talk to animals—the ability to feel what they feel and to experience life the way they do.

Perhaps it was those years of observation that enabled me to really see animal suffering. When a woman at my Quaker Meeting came and talked to us as children about why she was a vegetarian, it all made sense. In my freshman year of high school, I gave up eating meat and never regretted it. How could I cause the deaths of animals who were just like my friends? I wouldn’t eat my horse, my chickens, my cats, or my human friends—what was the difference between my friends and animals raised for slaughter? Suddenly, animal agribusiness seemed too much like slavery or the Holocaust. There was no way I was going to partake of the suffering and deaths of animals, for the mere pleasure of eating their flesh.

And yet, for years I continued to cause animal suffering through my food choices, although it took place in a subtler way. I was still a lacto-ovo vegetarian. I knew dairy cows are subjected to the same abusive conditions as "meat" cows, and when they stop producing enough milk they are slaughtered. I understood that dairy farmers do not keep and care for the male calves--but I didn’t look too closely. I turned a blind eye to the fact that the veal industry depends on the dairy industry. I was aware of the inhumane conditions in which egg-laying chickens are kept. And I knew that, like calves, the male chicks are killed, and the hens are killed when they don’t produce as many eggs as usual.

Despite that knowledge, I rationalized, I made excuses, I thought it would be too hard to become vegan. About two years ago, I decided to make a small step toward being vegan, something I could commit to and not worry that it would be beyond my willpower: I started to have vegan breakfasts. Then the rest of the day I could eat what I wanted. I became accustomed to this small step, and it helped me think – a little each day – about how I wanted to live my life. About a half a year ago, as the next step, I stopped bringing non-vegan food into my home, but I continued to eat what I wanted at friends’ houses and when I went out to eat.

At this last Thanksgiving (2007), I thought about all of those turkeys who were forced to give up their lives for tradition, for Americans’ thoughtlessness, for selfish pleasure. Around the same time, a friend asked me an innocent question: “you’re vegan when you break your fast, and you’ve stopped bringing non-vegan food into your home…when are you going to become vegan?” Somehow these things helped me open my heart and the knowledge sank through the chinks in my armor. I prayed, "Please, make it possible for me to live these beliefs. Help me continue to feel what I am feeling now, don’t let me lose my empathy, even when it is easier to be numb."

I seem to have gotten the help I asked for. It hasn’t been too hard for me so far, and I feel my life is more aligned with the Quaker Testimonies of peace, simplicity, equality, integrity, community, and unity with nature. So--if you’re struggling with the decision to become vegetarian or vegan, take heart! It is not such an enormous step after all, but if it's hard for you, take smaller steps. The help you need will be granted.

Sola Wolff researches, practices, and teaches a non-violent, non-coercive method of training animals. She currently lives in Arcadia, California, and occasionally attends Orange Grove Friends Meeting in Pasadena.

Pioneer: Tom Regan, Part II

In the last issue, we learned that a 1972 review in the New York Review of Books by the then little-known Oxford philosopher Peter Singer, of a collection of essays entitled Animals, Men and Morals, was a crucial event that sparked Tom Regan's interest in animal rights issues.

In the last issue, we learned that a 1972 review in the New York Review of Books by the then little-known Oxford philosopher Peter Singer, of a collection of essays entitled Animals, Men and Morals, was a crucial event that sparked Tom Regan's interest in animal rights issues.

He had an opportunity to talk several times with Singer at Oxford in the summer of 1973, and was further stimulated by Singer's subsequent book Animal Liberation. By 1975 he and Singer had put together a prospectus for an anthology of philosophical writings on the subject, Animal Rights and Human Obligations. Although the proposal at first produced nothing but amused laughter from the textbook editor to whom Regan took it, the book was published by his firm, and surprised both that editor, and Regan and Singer, by selling tens of thousands of copies.

The time obviously was right; change was in the air. Regan, by now himself a philosophy professor at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, found that college classes on animal issues multiplied from zero to many from 1975 on, and he himself was in demand as a lecturer around the country. He also published further on the topic: All that Dwell Therein: Essays on Animal Rights and Environmental Ethics (1982); his magnum opus, The Case for Animal Rights (1983); Animals Sacrifices (edited by Regan, 1986), then, after some writings on other philosophical topics , what many consider his most accessible animal books, Defending Animal Rights, and especially the powerful Empty Cages (2002). He also co-produced a film, We Are All Noah, and created The Culture and Animals Foundation.

Regan was also an activist for the animals during those years of scholarship. He lectured, sometimes under conditions of extreme opposition, including totally fabricated accusations that he advocated violence, even murder, on behalf of a cause for which he was (antagonists charged) nothing but a dangerous demagogue. In 1985, a lab tape "liberated" by the Animal Liberation Front, and distributed in edited form by PETA, showed a head-injury lab at the University of Pennsylvania to be carrying on cruel, even sadistic animal research, violating many federal guidelines. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) responded to the exposé by increasing the lab's funding! Expecting to be arrested, Regan took part in a sit-in demonstration at the NIH funding office, an event which, after four widely-publicized days of occupation, led the NIH to reverse the funding grant. (The police never came.) In 1990 he was co-leader of the most successful animal rights march in Washington to date, involving anywhere from 30,000 to 100,000 activists.

Now retired from teaching but hardly in the rocking chair, Tom Regan has both admonitions and admiration for the animal rights movement. He is disappointed in the way that, since the great march of 1990, it has tended to divide into various segments and does not speak with the unified voice it did then. At the same time, he is encouraged by the overall growth of the movement, and the numerous successes it has had along the way, although major cultural barriers have not yet been breached decisively.

One thing Regan has done in recent years is read deeply in the history of struggles for human justice, such as those for Native American, African American, Women's, and Gay/Lesbian rights, in the hope they will shed some light on the animal rights struggle. Indeed they have. He has found, for instance, that when such a campaign was in its initial phases, and perceived as "dangerously" radical, two powerful forces opposed it: organized religion and the "best" science of the day. To take one example, it is well known that in the ante-bellum South major churches vigorously defended slavery as "biblical," and academically well-placed anthropological scientists were not wanting to pronounce definitively on the mental inferiority of Africans, and their need to be in a state of servitude. The day is bound to come when the religious and scientific defense of animal enslavement will be looked at as most of us now perceive those pro-slavery efforts.

In his childhood Tom Regan was given exercises to strengthen a "weak" left eye that would not coordinate properly with the other. Looking into an ocular device that showed a cage to the left eye, and a bird to the right one, he was to try to unite the two images. People with normal eyes saw the bird in the cage; but, try as he might, Tom could not quite do it. "Others saw the bird as captive. I could only see the bird as free."

--Robert Ellwood

Summarized from Tom Regan's booklet

"The Life and Times of Tom Regan"

published the The Animals' Voice

www.animalsvoice.com

Poetry: Prayer for Gentleness to All Creatures

To all the humble beasts there be,

To all the birds on land and sea,

Great Spirit, sweet protection give

That free and happy they may live!

And to our hearts the rapture bring

Of love for every living thing;

Make us all one kin, and bless

Our ways with Christ's own gentleness!

--John Galsworthy (1867-1933)

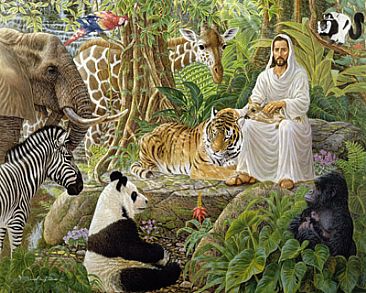

Painting by Daniel C. Toledo

Credits:

The Peaceable Table is

intended to resume the witness of that excellent vehicle of the Friends

Vegetarian Society of North America, The Friendly

Vegetarian, which appeared quarterly between 1982 and

1995. Following its example, and sometimes borrowing from its

treasures, we publish articles for toe-in-the-water

vegetarians as well as long-term ones, poetry, letters, book

and film reviews, and recipes.

The journal is intended to be

interactive; contributions, including illustrations, are

invited for the next issue. Deadline for the March issue

will be March 29, 2008. Send to graciafay@mac.com

or 10 Krotona Hill, Ojai, CA 93023. We operate primarily

online in order to save trees and labor, but hard copy

is available for interested persons who are not online.

The latter are asked to donate $12 (USD) per year if their means allow. Other

donations to offset the cost of the domain name, server, and

advertising notices are welcome.

Website www.vegetarianfriends.net

Editor: Gracia Fay Ellwood

Book and Film Reviewers: Benjamin Urrutia & Robert Ellwood

Recipe Editor: Angela Suarez

NewsNotes Contributors: Marian Hussenbux & Lorena Mucke

Technical Architect: Richard Scott Lancelot Ellwood

Lucretia Coffin Mott (pictured) and James Mott of Philadelphia. (Impressive though the work of these and other brave Friends may be, it should never be forgotten that the self-liberated persons themselves, facing death by torture, risked infinitely more.) . . . .

Lucretia Coffin Mott (pictured) and James Mott of Philadelphia. (Impressive though the work of these and other brave Friends may be, it should never be forgotten that the self-liberated persons themselves, facing death by torture, risked infinitely more.) . . . .

Alan Weisman, an award-winning international journalist, investigates in this book the question of what would happen on earth if the entire human race were to vanish--whether by a universal Rapture, an alien abduction, or a powerful virus.

Alan Weisman, an award-winning international journalist, investigates in this book the question of what would happen on earth if the entire human race were to vanish--whether by a universal Rapture, an alien abduction, or a powerful virus.

1 small yellow onion, chopped

1 small yellow onion, chopped In the last issue, we learned that a 1972 review in the New York Review of Books by the then little-known Oxford philosopher Peter Singer, of a collection of essays entitled Animals, Men and Morals, was a crucial event that sparked Tom Regan's interest in animal rights issues.

In the last issue, we learned that a 1972 review in the New York Review of Books by the then little-known Oxford philosopher Peter Singer, of a collection of essays entitled Animals, Men and Morals, was a crucial event that sparked Tom Regan's interest in animal rights issues.