Editor's Corner Guest Essay:

There is No Earthcare Without Animal Care

by M. P. Baumgartner

Recently I had the

pleasure of attending a conference at the Drew

Theological School on the topic of “Divinanimality: Creaturely

Theology.” One of the keynote speakers, theologian Jay McDaniel, raised

a question that I have often wondered about as well: Why do so many

people in the earthcare community seem to find it easier to care about

mountains and trees than about our much nearer relatives in the animal

kingdom? Why the leap from concern about humans to concern about air,

water, and soil, without a pause to consider the welfare of what

Buddhists recognize as the other “sentient beings” living alongside us?

Whatever the reason for the low priority given to animal rights and

animal welfare in so much environmental activism, the simple fact is

that ignoring animal concerns is a mistake for any environmentalist.

There can be no successful earthcare without animal care. Human and

nonhuman animals are bound together in complex interactions within our

shared environment, and what people do or do not do in regard to other

animals has a significant effect on us all.

Recently I had the

pleasure of attending a conference at the Drew

Theological School on the topic of “Divinanimality: Creaturely

Theology.” One of the keynote speakers, theologian Jay McDaniel, raised

a question that I have often wondered about as well: Why do so many

people in the earthcare community seem to find it easier to care about

mountains and trees than about our much nearer relatives in the animal

kingdom? Why the leap from concern about humans to concern about air,

water, and soil, without a pause to consider the welfare of what

Buddhists recognize as the other “sentient beings” living alongside us?

Whatever the reason for the low priority given to animal rights and

animal welfare in so much environmental activism, the simple fact is

that ignoring animal concerns is a mistake for any environmentalist.

There can be no successful earthcare without animal care. Human and

nonhuman animals are bound together in complex interactions within our

shared environment, and what people do or do not do in regard to other

animals has a significant effect on us all.Consider, for example, the consequences of human overpopulation. Estimates place the worldwide human population at about 200 million at the dawn of the Christian era, 700 million at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, 1.2 billion by 1850; 2.5 billion by 1950; about 7 billion today; and, if trends continue, 9 billion by 2050. As human numbers have soared, people have destroyed the habitats of thousands of other species in their ongoing quest for ever more land for their own settlements and crops. Human needs and appetites have also resulted in the exploitation of many nonhuman species beyond the ability of those species to remain viable. Many kinds of fish, for example, are on the brink of extinction due to overfishing by humans.

The result of human pressure on other species has brought about an ongoing wave of extinctions. Biologists call what is happening now the “sixth great extinction” in the history of life on earth. Great extinctions occur when at least 10% of species on earth are lost. All of the five earlier great extinctions were caused by volcanic or seismic activity on earth or by impact with bodies from space such as asteroids. The fifth great extinction, the last one before now, was marked by the extinction of the dinosaurs. Scientists estimate that as many as 40% of today’s species are currently threatened or endangered and may disappear by the end of this century. Among the animals currently facing extinction are tigers, pandas, mountain gorillas, whooping cranes, leatherback sea turtles, and many others. What kind of environment will be left if these and other creatures simply disappear? Extinctions are great blows to entire ecosystems, and some are worse than others. Biologist E. O. Wilson has observed, “If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.”

More evidence that environmental health depends on the treatment of nonhuman animals can be found in the context of meat eating. As human numbers have risen overall and as human prosperity has increased in many places, the human desire to eat meat has led to ever larger numbers of domesticated animals being raised for human consumption. Aside from the unspeakable suffering this has caused the animals involved, it has also led to great environmental harm and, ironically, to great risk to members of the human

community

as well. Among the

damaging consequences of meat eating are: deforestation and other

habitat destruction brought about by people who need room for their

livestock; pollution of the air (such as through the emission of

methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas, as a byproduct of digestion in

livestock animals), the pollution of water (as runoff from animal

excrement and other pollutants enters waterways); and famine and thirst

among poorer humans (as plant food and water that might nourish human

beings are given to livestock instead).

community

as well. Among the

damaging consequences of meat eating are: deforestation and other

habitat destruction brought about by people who need room for their

livestock; pollution of the air (such as through the emission of

methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas, as a byproduct of digestion in

livestock animals), the pollution of water (as runoff from animal

excrement and other pollutants enters waterways); and famine and thirst

among poorer humans (as plant food and water that might nourish human

beings are given to livestock instead).As humans have increasingly invaded and seized spaces from which they were previously absent—rain forests, caves, marshlands, and more—another source of environmental harm has emerged: new viruses and other infectious agents that can wreak havoc on entire populations. Sometimes these new infections affect people, sometimes nonhuman animals, and sometimes both groups alike. It is believed that HIV infection crossed from nonhuman primates to humans in the Congo region of Africa when humans began killing and eating jungle animals from previously pristine settings; Ebola fever appears to have been contracted from bats when people began exploring caves they had previously left alone. Health consequences for nonhumans have also been great. Among the species whose numbers have been decimated by exposure to new infectious agents introduced or spread by humans are bats (mortality rates of 90% and higher have followed the appearance of a fungus that causes “white nose” syndrome in bat colonies in the eastern United States); the Panamanian gold frog (the national symbol of Panama, which may already be extinct in the wild), and possibly honeybee colonies (where colony collapse disorder may be linked in part to new infections). Since bats and bees provide valuable services to humans through insect control and crop fertilization, respectively, the impact on people is likely to be considerable.

Aside from any impact on forests, rivers, crop plants, and oceans, however, the treatment of nonhuman animals by humans raises concerns of a moral nature. The more scientists learn about nonhumans, the more it appears that rationality, emotionality, and other “human” attributes are actually things we share with many nonhuman species. We now know that many nonhuman animals have conflicts and resolve them through peacemaking; enjoy painting and watching sunsets; innovate and problem solve to achieve goals, and more. People from faith traditions such as Jainism, Hinduism, and Buddhism have long recognized that nonhuman animals have moral rights; ethical philosophers like Peter Singer and Tom Regan have come to similar conclusions in our own time. As Quakers, shouldn’t we also come down on the side of compassion for nonhuman animals, not just because this will make our own environment better but because it is the right thing to do? Shouldn’t we join in the Buddhist prayer that asks that “all who have life be delivered from suffering”?

Reprinted with permission from the November 2011 issue of Spark, journal of New York Yearly Meeting of Friends. Permission from author sought.

News Notes

Keep the Claws on Those PawsIsrael has banned the declawing of cats, a practice that can cause ongoing physical and psychological suffering, the penalty being up to one year in prison and a $20,000 fine. See Claws on Paws. Also banned there are raising crocodiles for their skin and flesh, or ostriches for their skin, flesh or feathers.

--Contributed by Benjamin Urrutia

Greece Bans Animals in Circuses

After a campaign by Animal Defenders International and many other groups, Greece has outlawed the use of animals in circuses. Greece joins Bolivia, Peru, Austia, Portugal, Denmark, and Croatia who have (partial) bans or phase-outs on wild animal acts. See Circus Animal Ban--Contributed by Marian Hussenbux

Unset Gems: Tao Te Ching

I

have three treasures which I hold

I

have three treasures which I holdand keep.

The first is mercy;

The second is simplicity;

The third is daring not to take precedence over others.

From mercy comes courage;

From simplicity comes generosity;

From humility comes leadership.

Letter: Carl Sheppard

Dear Peaceable Friends,. . . . I had an aunt and uncle who owned a farm in Indiana that . . . was in many ways similar to your parents' farm as you described it in the December-January Editor's Corner. They also had dairy cows, chickens, and vegetable gardens; and my cousins helped my uncle with the chores in much the same way your brother did. . . . . They also struggled to make ends meet.

. . . One summer vacation when I was ten I went to visit their farm for a couple of weeks. After a few days there I found out my cousins were not going to have much time to play with me; it seemed to me they worked all day, so I decided I'd work too (I really just tagged along and got in the way). Once when my

cousins had

"gone to get some

chickens for dinner" I went along. I stood outside the coop and

my oldest cousin, who was sixteen, went into the coop while his

brother carried buckets of boiling water from the kitchen and poured

them into a big pail at the door of the coup. Before I realized

what I was going to see, my cousin chased down and caught a chicken,

grabbed her by the feet, put his boot on her head and pulled straight

up. The long neck hung down pouring blood, while he carted the

body over and dunked it in the boiling water. I almost got

sick. I didn't say anything, but I sure as heck left before he

got to Chicken Number Two.

cousins had

"gone to get some

chickens for dinner" I went along. I stood outside the coop and

my oldest cousin, who was sixteen, went into the coop while his

brother carried buckets of boiling water from the kitchen and poured

them into a big pail at the door of the coup. Before I realized

what I was going to see, my cousin chased down and caught a chicken,

grabbed her by the feet, put his boot on her head and pulled straight

up. The long neck hung down pouring blood, while he carted the

body over and dunked it in the boiling water. I almost got

sick. I didn't say anything, but I sure as heck left before he

got to Chicken Number Two.That night at dinner I didn't put any chicken on my plate; unfortunately, my uncle noticed. He asked me why, and I told him I wasn't hungry. He let it slide, but joked to his two sons that they must not be working me hard enough. I knew from that day that I'd never eat chicken again.

It was strange that I could go to the shed with my aunt while she got a piece of bright red beef out of the chest freezer and eat it at dinner--no problem--but no more chicken. I was worried what would happen when I got back home, for my mother had always been the "clean your plate" type. But when I explained to her what I had seen and how it affected me, she was kind enough to let me stop eating chicken. When the rest of the family had chicken I would usually eat a hamburger or a grilled cheese sandwich. I knew hamburger came from a cow, but somehow that violent chicken slaughter drew a line in the sand for me.

I appreciated your idea that animals are slaves, and people's assumption that they own them. I think that these two attitudes most of all are responsible for the terrible treatment and killing of beasts. We need to focus on these ideas most of all, before issues of nutrition or the environment, and bring them to the attention of people who eat flesh.

. . . . I loved the story of the caged rat rescued by the empathic rat; it reminded me of the Disney film The Rescuers Down Under. On the basis of such evidence, humankind must begin the accept the emotional traits and intelligence of animals, and weigh these factors in our treatment of them.

I have sent the recipes along to my newly vegetarian son. They sound delicious; I hope he tries them.

Recipes

Mushroom - Celery Heart SaladServes 4

2 cups celery hearts, sliced

1 cup cremini mushrooms, sliced

3 T. freshly squeezed lemon juice

1 head Bibb lettuce

4 oil-cured black olives

⅓ cup extra virgin olive oil

1/4 - 1/2 tsp. sea salt, or to taste

Freshly ground black pepper, to taste

In a medium size bowl, toss celery and mushrooms with 1 T. lemon juice; set aside. Place lettuce in a salad serving bowl. Add mushrooms and celery.

Mash olives in a small glass mixing bowl; using a wooden spoon, mix in olive oil and remaining lemon juice. Season with salt and pepper. Pour over mushrooms and celery. Toss gently and serve.

--Amgela Suarez

Galettes with Bitter Greens

serves 4

Galettes are a free style type of pastry or crepe.

2 T. Earth Balance Buttery Spread

1 small onion, finely chopped

3/4 cup minced fresh mixed greens (such as dandelions, spinach, parsley and basil)

1/2 - 3/4 cup almond ricotta (see below for recipe)

2 T. fresh marjoram, finely chopped

Chickpea crepes (see below for recipe)

In a medium skillet, saute in Earth Balance until onion is translucent. Add mixed greens and cook until tender, about 5 minutes. Remove from heat and allow to cool slightly. Stir in almond ricotta. Spread greens–almond ricotta mixture on crepes. Garnish with fresh marjoram. Galettes are served open, although they may be rolled in the style of traditional crepes if desired.

--Angela Suarez

Chickpea Crepes

makes about 14 crȇpes

1 cup organic chickpea (garbanzo bean) flour

1 cup organic unbleached flour

1 tsp. sea salt

2 T. extra virgin olive oil

2 cups spring water

In a medium size deep bowl whisk together the flours and sea salt. Vigorously whisk in the olive oil and water so that no lumps remain and the mixture is very smooth. This step may also be done in a blender, Then pour the batter into a medium deep bowl. Cover and let sit until ready to bake the crepes. While baking the crepes, place those already baked on a flat surface such as a cutting board, and separate with pieces of wax paper.

Crepes may also be wrapped in plastic wrap or additional wax paper and stored in the refrigerator overnight before filling. They also may be baked, wrapped and frozen for at least a week or so. Simply thaw, fill, and cook according to individual recipes.

--Angela Suarez

Almond Ricotta

makes 2 1/2 cups

1 cup

hot spring water

1 cup

hot spring water1/2cup whole blanched almonds

1 cup cold spring water

1 T. organic raw apple cider vinegar

1/4 cup cornstarch

1 T. safflower oil

1 tsp. evaporated cane juice

1/2 tsp salt

Place hot water and almonds in blender; blend until smooth and not grainy.

Add the rest of the ingredients, blend well again.

Pour into a small saucepan, stir constantly over medium-high heat until bubbly, reduce heat and cook one minute. Scrape mixture into glass container. Allow to cool. Whisk or stir with fork to give texture of ricotta. Store in refrigerator in glass container for up to one week.

-- Angela Suarez

Did You Miss This One? Animal Suffering and The Holocaust: The Problem with Comparisons

Animal Suffering and the Holocaust: The Problem

with Comparisons. By Roberta Kalechofsky. Marblehead, MA: Micah

Publications,

2003. Paperback, 60 pp. $10.00.

In the

interest of full disclosure, I will tell you I approached this

book with a fair amount of personally relevant history. As an

undergraduate, I was hired to do animal research. Years later, while a

biodecontamination specialist for Merck, I toured swine and poultry

facilities which motivated me to switch to a vegan diet, while keeping

my real reasons hidden from my customers and employer.

In the

interest of full disclosure, I will tell you I approached this

book with a fair amount of personally relevant history. As an

undergraduate, I was hired to do animal research. Years later, while a

biodecontamination specialist for Merck, I toured swine and poultry

facilities which motivated me to switch to a vegan diet, while keeping

my real reasons hidden from my customers and employer.Initially I didn't want to read this book – I usually avoid graphic descriptions of violence. But when I saw the author was responding to PETA's “Holocaust on your plate” campaign, I reconsidered. Years before I had ever heard of PETA's campaign, my work for Merck brought me to the World Poultry Expo, where I was horrified to see attendees enthralled by the latest technology for the killing and processing of chickens into cellophane-wrapped packages of meat. Seeing this equipment reminded me of the descriptions of Auschwitz I learned of in my Jewish education. I have a similar experience today, every time a truck carrying animals to slaughter goes by, and I reflect on the German citizens of the 1940's who saw Jews densely packed into trains on their way to concentration camps.

Kalechofsky's book packs a lot into its mere 60 pages. It is not an easy read, though it is quick, which is good, since the subject is intense, and the book's graphic descriptions of both human and animal suffering are disturbing. Additionally the vocabulary is of an extremely high level-–there were dozens of words I was unfamiliar with (apotheosis, schadenfreude, deophiliac, perfidious, dhimmi, atavism, quotidian, and eschatology, to name just a few.) These suggest to me that the author's intended audience is scholars, rather then the general reader.

The text begins by highlighting the differences between humans and other animal species while emphasizing the importance of historical context when considering various atrocities. Kalechofsky seems to argue against making comparisons between the sufferings of different groups, but then references the books The Dreaded Comparison: Human and Animal Slavery and Eternal Treblinka, and acknowledges that these authors effectively demonstrated that bad things done to animals, eventually are done to humans. In the end, I felt that the bulk of Kalechofsky's citations make a strong case for comparing human and animal atrocities-–but perhaps that is just reflective of my own bias. Regardless of how the reader interprets Kalechofsky's intent here, she deserves high marks for her research, and for succinctly summarizing and quoting many historical figures, like Claude Bernard, the father of physiology. She has done a superb job of providing a road map through the evolution of vivisection, and the intentional cultivation of “detachment” by its early proponents, while highlighting the downsides of such to society as a whole.

While I found the historical references informative, what will keep this book a permanent part of my literary collection will be its usefulness to me as a rich source of quotes and excerpts for my writing and sharing with friends and the wider community on the subject of abolition.

--JoAnn Farb

Author of Compassionate Souls: Raising the Next Generation to Change the World

Book Review: How the Dog Became the Dog: From Wolves to Our Best Friends.

Mark Derr, How the Dog Became the Dog: From Wolves to Our Best Friends. New York and London: Overlook Duckworth, 2011. pp. 287. $26.95. Why

is it that the wolf, partially disguised through millennia of

selective breeding to become the dog, has shared the lives of humans

over so many years -- not just as “livestock,” but as intimate

companion, coworker, trusted friend?

Why

is it that the wolf, partially disguised through millennia of

selective breeding to become the dog, has shared the lives of humans

over so many years -- not just as “livestock,” but as intimate

companion, coworker, trusted friend?Mark Derr endeavors to explore this mystery in a fascinating book combining genetics, anthropology, history, and an obvious personal love for dogs. In brief, he believes that this relationship goes back very far, quite possibly as far back as 135,000 years ago. Genetic evidence suggests it was then that wolves and dogs first began to split into the two closely-related species. This would have meant a canine relationship with Neanderthal humans, long before the emergence of that strand we are pleased to call homo sapiens, and long, long before the invention of agriculture (a mere 12,000 years or so ago). However, definite fossil evidence of the association of dogs with humans dates from no more than some 35,000 years before the present, and more cautious scholars would not advocate an earlier date. This would make dogs appear in their symbiotic role with humans along with homo sapiens and the famous cave paintings.

Only with seed planting twelve millennia past came also the domestication of other animals. There is no evidence that the dog's great rival for human companionship, the cat, coexisted with us till around the same time, when s/he was perhaps drawn to the granaries of the first farmers, and served to protect them from rodents. As for another creature capable of no less profound bonding, the horse's transportation usefulness to humans out on the steppes of central Asia was not discovered till even later.

But the dog, Derr avers, has a far longer lineage, and ever more interestingly, his/her bonding with humans was a mutual choice, not one imposed by the biped species. This author believes that certain wolves began to hang out near Neanderthal camps or caves looking for scraps, and soon were also, of their own volition, accompanying their new human companions on hunting expedition as though the two kinds of beings together were a new kind of pack. The different talents of the two, dogs with their acute sense of smell for tracking and their speed for assault, humans with their throwing and tool-making skills, worked together well. Soon other virtues of comradeship emerged: watchdog capabilities on the one hand, provision of warm secure quarters, especially for breeding, on the other. As Derr put it, “More profoundly, and mysteriously, human and wolf both recognized at some primal level that they belonged together.”

Needless to say, those wolves who chose this new

symbiotic way of life

with humans bred with one another, and gradually changed into something

other than what they were at the outset. Some changes were natural.

Others were arbitrated by humans wishing to makes dogs of all different

sizes, colors, and shapes as they are now. Some of these variations,

such as the short nose of the bulldog, are

little more than grotesque deformities compared to what dogs were

originally, and it is often recognized that those large

alert types nearest to the wolf are the healthiest and most intelligent

of this remarkable species. But this is nothing against persons who

like poodles

or chihuahuas; the very distinctive dogs need love and can give love

too.

Needless to say, those wolves who chose this new

symbiotic way of life

with humans bred with one another, and gradually changed into something

other than what they were at the outset. Some changes were natural.

Others were arbitrated by humans wishing to makes dogs of all different

sizes, colors, and shapes as they are now. Some of these variations,

such as the short nose of the bulldog, are

little more than grotesque deformities compared to what dogs were

originally, and it is often recognized that those large

alert types nearest to the wolf are the healthiest and most intelligent

of this remarkable species. But this is nothing against persons who

like poodles

or chihuahuas; the very distinctive dogs need love and can give love

too.Although certain passages on DNA and the like may be a bit technical for some readers, overall Hows the Dog Became the Dog is a great read for dog lovers, animal lovers generally, and especially those interested in the anthropology of human-animal relations. Those of us who disavow hunting and the consumption of animal flesh altogether may dislike the probable relationship of hunting to original dog-human partnering. But little in human history is without ambiguity, and the real question on the human-animal relationship is not where it came from but where it is going--its future. Here the wonderful love and life-sharing that innumerable people have with dogs, and dogs with them, can serve as a model and foretaste of that Day when all species shall live together in peace, and none shall hurt nor destroy on all God's Holy Mountain.

In the area surrounding our home, coyotes are often seen and heard, and I have seen dogs perk up and look a bit wistful at the sound of their cry, or at the sight of a small group of these untamed relatives afar off. Perhaps something in their DNA harks back over a thousand millennia and causes dogs to wonder anew what it would be like to live the hard but wild and free life of their kind in a primordial pack/family. But generally the canine will then turn around, look up at her human companion, perhaps nuzzle her or his hand, as though to recognize that this is life now, here lies our future. May we humans be worthy of their trust.

--Robert Ellwood

Pioneer: David Maxwell Whiting

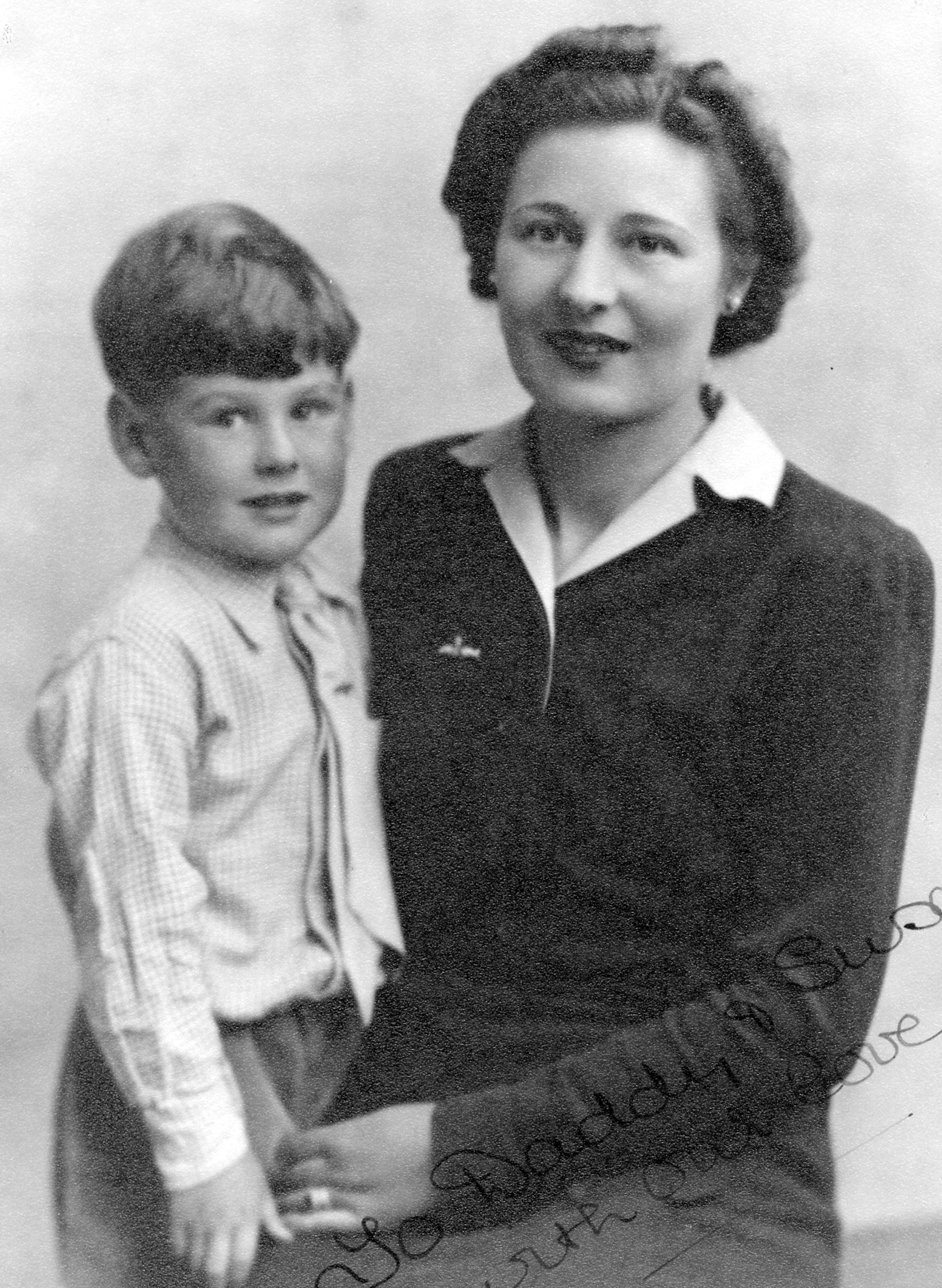

David

Whiting was born in England just before the 2nd World War, the only

child of Muriel and Jack Maxwell Whiting. It seems he chose his

ancestors with some care, as both his maternal grandmother, Hilda

Albino, and his mother Muriel were vegetarian. (For Muriel's

Pioneer story, see PT 74). Their

commitment (and that of David's aunt Kathleen, "Totty,") arose out of

their Theosophical convictions of a oneness underlying all living

beings, giving rise to their work in meditation and healing prayer

circles. They abstained from eating flesh both for the sake of

the animals, and because they were convinced that slaughterhouse

products carry strong negative vibrations of fear and suffering which

hinder the healing energies. David's father, Max, essentially

agreed with their views, but was not actively involved; later David

also

David

Whiting was born in England just before the 2nd World War, the only

child of Muriel and Jack Maxwell Whiting. It seems he chose his

ancestors with some care, as both his maternal grandmother, Hilda

Albino, and his mother Muriel were vegetarian. (For Muriel's

Pioneer story, see PT 74). Their

commitment (and that of David's aunt Kathleen, "Totty,") arose out of

their Theosophical convictions of a oneness underlying all living

beings, giving rise to their work in meditation and healing prayer

circles. They abstained from eating flesh both for the sake of

the animals, and because they were convinced that slaughterhouse

products carry strong negative vibrations of fear and suffering which

hinder the healing energies. David's father, Max, essentially

agreed with their views, but was not actively involved; later David

also  embraced

these moral standards. The photo shows him at about age three

sitting on the steps to a room dedicated to meditation, prayer and

healing which his grandmother Hilda had set up in a barn in her garden

near Tunbridge Wells.

embraced

these moral standards. The photo shows him at about age three

sitting on the steps to a room dedicated to meditation, prayer and

healing which his grandmother Hilda had set up in a barn in her garden

near Tunbridge Wells.After WWII came, Max Whiting managed to get released from his "reserved" classification, and joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR), becoming a Pilot Officer Flight Engineer on a Lancaster bomber squadron. As Christmas approached in 1943, when Muriel was making preparations for him to come home on leave, five-year-old David asked her "Has my Daddy been killed yet?" When she assured him that his father was not only alive but would soon be home for a visit, David explained, "I only asked because I had not seen him lately. But he will be killed . . ." Again she reassured him. Later she came to believe that this grim knowledge, which because of her kind wish to protect him he had to bear alone, may have contributed to his becoming seriously ill with bronchial pneumonia and the asthma he has suffered from much of his life.

His

father did come home for that Christmas leave, and David's health

improved in the following months. But on 22 May 1944 Muriel

received the terrible news that Max’s Lancaster bomber from 630

Squadron was missing, There followed a long period of grief,

suspense, anxiety, and faint hope. In 1946 Muriel's stepfather

encountered, apparently by chance, a Danish farmer who told him that

Max's Lancaster had been shot down near his farm on the Danish coast

with the loss of all the crew. The villagers had set up a

memorial stone, with individual stones naming the seven airmen.

The farmer gave Muriel's stepfather a small photo of the memorial

site. Thus at age five David became fatherless.

His

father did come home for that Christmas leave, and David's health

improved in the following months. But on 22 May 1944 Muriel

received the terrible news that Max’s Lancaster bomber from 630

Squadron was missing, There followed a long period of grief,

suspense, anxiety, and faint hope. In 1946 Muriel's stepfather

encountered, apparently by chance, a Danish farmer who told him that

Max's Lancaster had been shot down near his farm on the Danish coast

with the loss of all the crew. The villagers had set up a

memorial stone, with individual stones naming the seven airmen.

The farmer gave Muriel's stepfather a small photo of the memorial

site. Thus at age five David became fatherless.While searching for news of her husband, David’s mother met Hugh Dowding (see Pioneer, PT 81) who shared her involvement in spiritualism; after several years, they were married in 1951.. Lord Dowding was responsible for creating the air defence of the British Isles that, under his command, led to victory in the Battle of Britain forcing Hitler to abandon his invasion of England. Soon Hugh also came to share her compassion and to see the importance of Muriel’s work for animals, often speaking in their defence in the House of Lords. Hugh became a wise and nurturing second father to David, encouraging his interest in engineering, which later became his career in aeronautics.

Sent to a preparatory boarding school for boys at the age of seven, David, a small, scrawny child, was often picked on by the other children, and caned for performing badly at school, as his dyslexia was not then recognised. Like his mother he had a natural compassion for animals, whether cradling an injured bird in his hands, or, as his house master recalls, stopping during a cricket game to rescue a beetle from the wicket. His spirit was not crushed by the frequent punishment but he still maintained his mischievousness.

When he was twelve he went to Long Dene School in Kent, an experimental community which stressed vegetarianism and having the children share the work of growing their own healthy food. Here David aged thirteen was now able to make his commitment to vegetarianism, and kept it. (At roughly the same time, his stepfather made the same commitment after investigating several slaughterhouses for his speeches in the Upper House of Parliament.) When Long Dene closed its doors in 1954, David's mother found another vegetarian school, Wennington in chilly Yorkshire, founded by Quakers Kenneth and Frances Barnes. The Quaker testimony of Equality was built into school policies; special treatment according to gender and social status were rejected, and the children participated in the work of maintaining the school.

David pursued a career in aeronautical engineering until the death of Lord Dowding in February 1970. With the loss of his stepfather he abandoned his career to support his mother in the work of Beauty without Cruelty that she had founded and to follow issues that Dowding had debated for animals in parliament. He taught himself to use a 16mm camera, and became a roving investigator gathering the essential evidence of the animal abuse that his mother was bringing to public attention. He felt he was motivated and protected from many dangers he encountered by an unseen force that transcended his individuality; he was merely a representative of the animals. He trained himself to be objective, setting aside feelings of horror and revulsion while photographing the most abominable cruelty, a stance important both for his sanity and his safety. For example, one of his early projects (1973) was filming the killing of harp seal cubs on ice floes far out from Newfoundland, where a dispassionate attitude protected him from the wrath of the seal killers. "One push off the rafting ice into the water, and you would last just three minutes." But his true feelings were never far away, and would flood him when he was editing his work,

In 1974 when his

mother was publicizing the slaughter of Karakul

lambs, aborted or killed shortly after birth for their tightly curled

fur known as astrakhan, Swakara, or broadtail, David fitted out an old

Land Rover and set off for Iran, Afghanistan and India to get evidence

on film. To orient himself, he infiltrated a large reception held

by the chief of police at the Mashhad hotel in Iran; and by talking to

this chief and others, he was able to establish a contact who knew the

nomadic tribes involved in the karakul trade. Later, by dropping

the name of his "friend" the chief of police, he was able to get the

three different permits necessary to get to the remote politically

sensitive boarder locations where the nomadic tribes roamed with their

flocks, and to film the slaughter.

In 1974 when his

mother was publicizing the slaughter of Karakul

lambs, aborted or killed shortly after birth for their tightly curled

fur known as astrakhan, Swakara, or broadtail, David fitted out an old

Land Rover and set off for Iran, Afghanistan and India to get evidence

on film. To orient himself, he infiltrated a large reception held

by the chief of police at the Mashhad hotel in Iran; and by talking to

this chief and others, he was able to establish a contact who knew the

nomadic tribes involved in the karakul trade. Later, by dropping

the name of his "friend" the chief of police, he was able to get the

three different permits necessary to get to the remote politically

sensitive boarder locations where the nomadic tribes roamed with their

flocks, and to film the slaughter.That same year, he went undercover in Ethiopia to film the battery-cage farming of wild civet cats for the musk used in perfumes, which is scraped from glands by the anuses of these tormented animals. Again with difficulty he found out by unconventional ways where some musk farms were located, mostly very small-scale. These defenceless creatures were kept in small rough wooden cages on trestles in low filthy sheds that were filled with acrid smoke to keep down the flies. Not so fragrant. . . . But the result was that many women learned of this innocent suffering and swore not to use perfume made with musk from civet and the Siberian musk deer.

These are far from being the only remote places where David has travelled to obtain firsthand evidence, and when arrested for spying in South Africa he acquired the name, "animal spy." His adventures range from filming the

massacre of the (South African) Cape fur

seal to recording the killing of the musk deer high in the

Nepalese Himalayas (which included getting lost at 16,000 feet in a

leech-infested forest). He investigated the snaring of elephants

for their ivory in the then Rhodesia; close to home in Britain, he

exposed the appalling treatment of animals in fox and mink fur farms as

well as in slaughterhouses.. Due to his films and ten-year

campaign exposing the cruel massacre of hundreds of tons of

ecologically valuable bull frogs, where their legs were exported as a

food delicacy, this trade was banned by the Indian Prime Minister.

massacre of the (South African) Cape fur

seal to recording the killing of the musk deer high in the

Nepalese Himalayas (which included getting lost at 16,000 feet in a

leech-infested forest). He investigated the snaring of elephants

for their ivory in the then Rhodesia; close to home in Britain, he

exposed the appalling treatment of animals in fox and mink fur farms as

well as in slaughterhouses.. Due to his films and ten-year

campaign exposing the cruel massacre of hundreds of tons of

ecologically valuable bull frogs, where their legs were exported as a

food delicacy, this trade was banned by the Indian Prime Minister. In David's world-wide investigations he mainly worked undercover in places where a vegetarian diet was unavailable; for example, during the Canadian seal hunt he survived mostly on boiled potatoes. Due to protocol and the need for politeness to their hosts, David and his mother’s public life has hindered them from keeping to their ultimate goal of a vegan lifestyle.

Looking back over his years of activism in the light of the present scene, David comments "Dad (Hugh Dowding) told me never to take anyone's word for anything of importance, but that one should go and see for oneself. That's what I did, and it seems I have perhaps been a catalyst, helping to bring about change for the better. . . . “It's fulfilling to see so many bright and dedicated young people taking up the challenge in so many ways to continue the work that my parents pioneered in the 1950s. I was fortunate to have had the opportunity to make a small contribution, I hope, and meet many remarkable people without whom my efforts would have failed. I believe we are part of a diverse team guided by unseen hands”.

Sources: E-mail communications from David Whiting; The Psychic Life of Muriel, the Lady Dowding: An Autobiography; and "The Dowding Legacy" by Tony Wardle, Viva!Life, Issue 48, pp. 28-29. Used with permission.

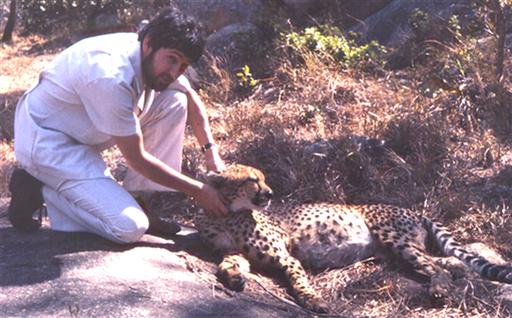

The fourth photo shows David enjoying a quiet moment with a cheetah friend in Rhodesia, 1975.

Poetry: Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1803-1882

Christina Rossetti (1830-1894)

The mountain and the squirrel

The mountain and the squirrelHad a quarrel,

And the former called the latter "Little Prig."

Bun replied,

"You are doubtless very big,

But all sorts of things and weather

Must be taken in together

To make up a year

And a sphere.

And I think it no disgrace

To occupy my place.

If I'm not so large as you,

You are not so small as I,

And not half so spry;

I'll not deny you make

A very pretty squirrel track.

Talents differ; all is well [if] wisely put;

If I cannot carry forests on my back,

Neither can you crack a nut."

--R.W.E.

The Caterpillar

Brown and

furry

Brown and

furryCaterpillar in a hurry,

Take your walk

To the shady leaf, or stalk,

Or what not,

Which may be the chosen spot.

No toad spy you,

Hovering bird of prey pass by you;

Spin and die,

To live again a butterfly.