Editorial: Taking the Adventure

A Feast and a Paradox

On the third Sunday afternoon of each month, the members and supporters of the Animal Kinship (AK) Committee (sponsor of The Peaceable Table) gather to discuss business. Since most of us come directly from Meeting for Worship, a little refreshment is in order first. With much help from our clerk Kate's culinary skills, this potluck luncheon has evolved into a feast of abundant, colorful, and luscious gifts from Earth's bounty. Looking at this wonderful abundance of good things, and the caring and enthusiastic fellow-Friends seated around the table, I always feel an immense gratitude that was virtually unknown to me in the days before I came to embrace a "restricted" vegan diet. A feast is more than a meal; it is a refreshing communal celebration of plenty and life and joy and love. Especially when no innocent blood was shed in its preparation!

Yet one of our main motivations as Friends, as with any spiritually-oriented vegans, is a commitment to Simplicity of lifestyle, to taking no more than our share in a world in which our planet is being devastated and millions do not have enough to sustain life adequately, while others take more than they need. How can this crucial life-principle be compatible with the rightness of sitting down to so abundant a feast?

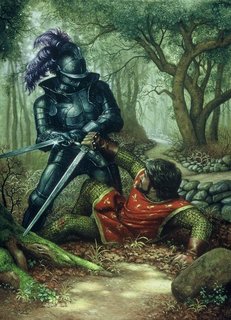

Knights and Dragons

A complex of images that suggests an answer to this question, and other related questions, can be found in an unlikely place: the stories of King Arthur's knights and the Quest for the Holy Grail. That this source is unlikely hardly needs emphasis. To begin with, the stories appear, confusingly, in a number of different versions, with varying implications. Even more problematic, in most of the tales the exploitation of animals is taken for granted. The knights' chargers are slaves controlled by bit and bridle; hunting, especially of deer and wild pigs, may be frequent; virtually every feast is centered in a corpse. The stories have touches of anti-semitism. Furthermore, the whole cycle is heavily male-centered, with female figures tending to be either either dangerous temptresses or sorceresses, or helpless Damsels in Distress. Problems are usually solved with the sword.

Then what is left? Quite a lot, actually. The Arthuriad took shape in a medieval world where civilization and order still had a shaky hold, where justice and peace were dreams--dreams that coalesced around valiant heroes who cared about the defenseless and could challenge the evil knights and the dragons of chaos who threatened to crush them. What with widespread subjection of women, with enforced marriage and rape by marauding knights or Norsemen, probably most damsels were in distress much of the time. In general, the poor of both sexes were subject to the casual violence of the powerful.

Modern Damsels

In our culture, concepts of women as frail beings needing protection and control are rightly seen by most as false and harmful. But that there actually are millions of defenseless beings in the clutches of agribusiness's robber barons--including damsels in terrible distress in dairy and egg factories--is indisputable. The victims are many, the champions few.

Does this mean we cast ourselves in the role of the Knights in Shining Armor who ride out to give battle to the dragons and blood-splattered oppressors? Well--no and yes. A minority of animal defenders evidently do, in a semi-literal manner: their sword-thrusts are shouts of abuse and violent phone calls, harassment of abusers' families, even bombing threats--sometimes carried out. Unhappily, this conspicuous minority is often seized upon by the press, eager to present a dramatic image of animal defenders as a violent lot. With friends like these . . . we need to proceed with Care.

Without seeing ourselves as sword-wielding warriors, we can still find the knight-in-armor image helpful. It can inspirit an activist not oversupplied with courage who faces, with beating heart, the prospect of civil disobedience in a literal rescue--or even just speaking up to her church, Meeting, temple, or family members on behalf of the animals. On the other side, the drama implicit in the images can be helpful in enabling us to get some distance on ourselves and on our mission, perhaps laugh at ourselves a little. Dragons, however terrifying, are mythological beasts!--and our Black Knights are not what they seem, either. The victims are very much physical beings, in physical chains, but not so the oppressors. Hidden in the heart of the hardest and greediest robber baron is the divine Light/Love, the seed of transformation. Our war, as St. Paul says, is not against flesh and blood but against the Principalities and Powers, against enslaving institutions and prejudices entrenched throughout society.

Behind the Black Visor

Remarkably, one of the narratives of the Arthurian epic already exemplifies this truth in a powerful way. It is the cycle of stories about Balin, together with his beloved brother Balan (the names suggest they are twins) a Knight of the Round Table. Sir Balin is a zealous but undisciplined warrior determined to be the Bravest Fighter on behalf of the Worthiest Cause. In the first story he comes under the spell of an accursed sword; inflamed by a desire for its power, he seizes it. The curse follows him: later, pursuing an evil knight into and even through the hallways of the Castle of the Grail, he bursts into the holy chapel where the sacred Chalice and Spear are kept. When the guardian of the Grail, the Fisher King, tries to block his intrusion, Balin grabs the Spear and with it wounds the King. The result of this Dolorous Blow is that all the countryside for miles around withers into a perpetual Waste Land; furthermore, the castle and the chalice disappear from ordinary sight, withdrawn into another  plane of being.

plane of being.

In a still later story Balin approaches a strange castle and is challenged to fight its champion, a black-armored knight with no identifying device on his shield. Unable to bear being thought a coward, Balin borrows a shield himself and gives battle. Both opponents fight valiantly, finally giving one another mortal wounds. But before they die, Balin raises the visor covering his enemy's face. What he sees is the face of his brother.

Today's Knights in Shining Armor--the small handful of animal defenders whose hearts burn to save all the billions of innocents from hellish suffering and death at the hands of animal agribusiness--are dwarfed many times over by their giant opponents. Imagine a Friend or church member trying to persuade her spiritual community (which may contain perhaps a hundred people out of the three hundred million in the US--to show compassion to animals by not eating them. He or she may be repeatedly blocked by a few other members, otherwise good people who refuse to see the monstrous evil they are championing. Another example: a small group doing a midnight open rescue know they can save perhaps twenty hens out of a hellhole containing two hundred thousand--and they know what will happen to all the others. In so grotesquely unequal a situation, with its painful frustrations, how does a defender bear in mind that the human beings whose callous and violent acts they are opposing are, under their visors, her own sisters and brothers? How does she hold this knowledge in her heart so that she can resist the temptation to hate and attack them even in her thoughts?

The Chalice of Light

The Arthurian stories contain another important theme, the Quest for the Holy Grail, which can help us meet this formidable challenge. The background of the story is the Waste Land, which had lain desolate for years. Linked to this situation of death was a mysterious seat at the Round Table, the Siege Perilous. It had long stood empty until finally taken by the High Prince Galahad, young offspring of the tragic affair of the enchanted Sir Lancelot and the Princess Elaine of the Grail Castle.

The Arthurian stories contain another important theme, the Quest for the Holy Grail, which can help us meet this formidable challenge. The background of the story is the Waste Land, which had lain desolate for years. Linked to this situation of death was a mysterious seat at the Round Table, the Siege Perilous. It had long stood empty until finally taken by the High Prince Galahad, young offspring of the tragic affair of the enchanted Sir Lancelot and the Princess Elaine of the Grail Castle.

That same day, the Feast of Pentecost at Camelot, the knights all heard a peal of thunder and saw a blaze of celestial light, in the midst of which appeared the Holy Grail. Awestruck with wonder, when it vanished they each vowed to go on quest to find it. Most of them wandered about, distracted by other adventures, and some never returned. In one version it was only three, whose dedication to the cause was deeper, that were able not only to find but to enter the elusive Grail Castle. Sir Lancelot, whose heart was divided between Queen Guinevere and the Quest, fell into a deep trance outside the castle, and got no further. Sir Bors and Sir Percival entered the castle hall and saw the procession of the glowing Grail and Spear, but were struck dumb and deprived of initiative. Only Sir Galahad was able to act, asking the crucial question: "Whom does the Grail serve?" He was also able to take the chalice and look into it. The blaze of light from the heart of the Cup permeated and galvanized him, and he was translated from the human plane into the Light. He had "achieved the Grail." The wounded Grail King was healed, and the new life of Spring came at last to the Waste Land.

To Will One Thing

Although medieval readers apparently admired Sir Galahad, modern readers are likely to find him problematic. He is described as a magnificent knight, but he seems scarcely human; totally dedicated to his mission to find and achieve the Grail, he has no friendly warmth, no weakness with which we can identify. His saying "My strength is as the strength of ten because my heart is pure," needs translation if we are not to dismiss him as an ego-bound brat.

Who and what is this High Prince? We may find some help from Soren Kierkegaard's line "Purity of heart is to will one thing." If we say that Sir Galahad's strength is as the strength of ten because his heart is one, that oneness being intent on the Source of Light, we will begin to understand why he is the only knight who achieves the Grail. Like the child in the Peaceable Kingdom scene who leads the lion and plays over the adder's den, Galahad represents the dimension of a human being that is linked to the Infinite. In a sense, he has always been gazing into the Divine Light, and thus is able to act with the Divine strength.

Who and what is this High Prince? We may find some help from Soren Kierkegaard's line "Purity of heart is to will one thing." If we say that Sir Galahad's strength is as the strength of ten because his heart is one, that oneness being intent on the Source of Light, we will begin to understand why he is the only knight who achieves the Grail. Like the child in the Peaceable Kingdom scene who leads the lion and plays over the adder's den, Galahad represents the dimension of a human being that is linked to the Infinite. In a sense, he has always been gazing into the Divine Light, and thus is able to act with the Divine strength.

If we interpret the High Prince in this way, the image suggests that every action of ours to champion the victims of oppression and violence must also be our inner Galahad's Quest for the Grail. Unless we are informed by and intent on the Light/Love of God in all our work, we are in danger of falling to burnout or distraction. Worse, we may become like Sir Balin, assertive and well-intentioned, but undisciplined, blinded, and led astray by self-dramatizing passion. The result is calamity. But if we hold to the more difficult path of following the gleam of the Light within, we may begin to tap into its power to transform even the Waste Land, which our earth is rapidly becoming, back into the Garden of God.

Bread for the Journey

We can now see the outlines of an answer to the question with which this essay began: how is the bounty of a feast to be held in balance with the modest fare appropriate for those who are all too aware of the distresses of the world around them? The feast has its place: from time to time, especially on Pentecost, the knights gather at the Round Table to enjoy abundance and good fellowship, to hear of some great deed, and to be available to the call. But feasts are relatively infrequent, and when the call to adventure comes, one must be ready to leave behind things that may be good in themselves, to travel light. We remember that there are no supermarkets available to the adventuring knight, and he ( she) cannot count on taking time out to look for whatever wild berries or herbs may particularly please the palate--and this knight is hardly about to seek out and kill an innocent creature for supper! He carries what food he can in his bag; she dines moderately. Those on Quest do not complain about plain food or inconvenience, because have more urgent things in mind.

Let us take the Adventure that is sent us.

—Gracia Fay Ellwood

The painting of Galahad is by George Frederic Watts.

We invite responses to editorials or any other feature of PT for our next issue's letter column: graciafay@gmail.com.

Activist Maru Vigo, whose letter appeared in

Activist Maru Vigo, whose letter appeared in  A German study of magpie behavior reported by Reuters breaks the news that these remarkable members of the crow family can recognize themselves in a mirror. As with elephants, a magpie who had had a yellow mark put on her black feathers would scratch at the mark in a mirror, a sign she realized that what she saw was not another bird but an image of herself. The capacity for self- recognition has been found in primates, elephants, and dolphins, but this is the first known instance in a bird. See

A German study of magpie behavior reported by Reuters breaks the news that these remarkable members of the crow family can recognize themselves in a mirror. As with elephants, a magpie who had had a yellow mark put on her black feathers would scratch at the mark in a mirror, a sign she realized that what she saw was not another bird but an image of herself. The capacity for self- recognition has been found in primates, elephants, and dolphins, but this is the first known instance in a bird. See  This book is a firm and thoughtful reproof of the use of violence, vituperation and coercion in defense of animal rights and environment. Such aggressive tactics are not only condemned as immoral and wrong, they are shown to be counterproductive. A notable example is the one that gives the book its title. To force a farm to stop raising guinea pigs for use in laboratory experiments, militant English activists stole the mortal remains of family relative Gladys Hammond, deceased at age 82 in 1997. Public opinion was horrified and disgusted by such blackmail combined with grave desecration. The guinea pig farmers were seen as the victims, not the perpetrators, of evil. The farm went on exploiting other animals and the labs obtained experiment victims elsewhere, so no worthwhile end was achieved that might justify the means.

This book is a firm and thoughtful reproof of the use of violence, vituperation and coercion in defense of animal rights and environment. Such aggressive tactics are not only condemned as immoral and wrong, they are shown to be counterproductive. A notable example is the one that gives the book its title. To force a farm to stop raising guinea pigs for use in laboratory experiments, militant English activists stole the mortal remains of family relative Gladys Hammond, deceased at age 82 in 1997. Public opinion was horrified and disgusted by such blackmail combined with grave desecration. The guinea pig farmers were seen as the victims, not the perpetrators, of evil. The farm went on exploiting other animals and the labs obtained experiment victims elsewhere, so no worthwhile end was achieved that might justify the means. He Followed Me Home--Can I Keep Him?

He Followed Me Home--Can I Keep Him?  12 large collard green leaves

12 large collard green leaves In the sixth and seventh centuries, not long after the times of the historical Arthur, there lived an Irish princess named Melangell. A strong woman, she refused to enter a dynastic marriage, and instead ran away to become an anchoress in the woods of Wales. One day a coursing (hare-hunting) party led by a prince named Brochwel pursued a hare into a thicket in a valley, only to find, in a little clearing, their prey nestled in the skirts and cloak of a young woman in prayer. It was none other than Melangell. Brochwel ordered his dogs to attack; they tried to do so but were stopped short by what seemed to be a protective shield around her.

In the sixth and seventh centuries, not long after the times of the historical Arthur, there lived an Irish princess named Melangell. A strong woman, she refused to enter a dynastic marriage, and instead ran away to become an anchoress in the woods of Wales. One day a coursing (hare-hunting) party led by a prince named Brochwel pursued a hare into a thicket in a valley, only to find, in a little clearing, their prey nestled in the skirts and cloak of a young woman in prayer. It was none other than Melangell. Brochwel ordered his dogs to attack; they tried to do so but were stopped short by what seemed to be a protective shield around her. It is interesting that a story with almost the same scenario and kinds of characters is told of St. Giles, who lived a century later in south France: the highborn individual who renounces all to become a hermit; a royal hunter; a wild animal (a doe in Giles' case) who is shielded; a spiritual opening for the hunter, and his request that a monastery be built on the site. Giles takes the arrow intended for the doe, a deed heroic, even Christlike, but not requiring paranormal powers.

It is interesting that a story with almost the same scenario and kinds of characters is told of St. Giles, who lived a century later in south France: the highborn individual who renounces all to become a hermit; a royal hunter; a wild animal (a doe in Giles' case) who is shielded; a spiritual opening for the hunter, and his request that a monastery be built on the site. Giles takes the arrow intended for the doe, a deed heroic, even Christlike, but not requiring paranormal powers.  Calling "Follow, follow the Gleam

Calling "Follow, follow the Gleam